Opinion | We’re Not All In This Together

“We’re all in this together.” It is a familiar pandemic-era mantra; an assurance that, no matter how hard your life may be right now, we all understand what you’re going through. However, branding COVID-19 as a universal equalizer is ignorant of the ways in which the virus disproportionately affects disadvantaged populations. This ignorance includes the belief that the pandemic’s reach extends only to social distancing orders, when, in reality, an event of this magnitude will only exacerbate the effects of systemic inequality and leave the world’s poorest people struggling through a devastating economic crisis.

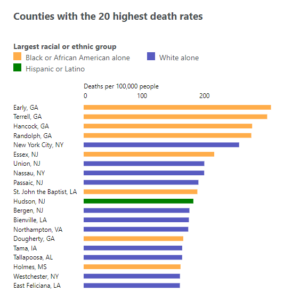

It is no secret that vulnerable communities are more at risk of contracting COVID-19. In the United States, African Americans account for 13% of the population but make up 25% of COVID-19 deaths – and that’s only for cases where race is known. In Canada, the social determinants of health, like race, income level, education, and access to healthcare services are simply not reported with COVID-19 death rates. It is therefore currently impossible to grasp the full extent of the virus’ impact on marginalized populations in Canada, but we can look at the pandemic’s effect in specific communities to gain some insight. For example, the borough of Montreal-Nord has the highest number of COVID-19 cases on the island of Montreal. Residents of Montreal-Nord are among the most vulnerable in Canada; the majority of them are a visible racial minority, make less than $50,000 per year, and lack a high school diploma. One can assume that, in communities like Montreal-Nord, social distancing is nearly impossible: many residences are crowded, and the few people who are able to retain employment are unable to work remotely or are deprived of sufficient safety measures at their jobs. Evidently, social distancing is a privilege, and not a right.

Vulnerable populations worldwide have been disproportionately suffering from the effects of the pandemic, even when social distancing is possible, with little acknowledgement from government officials or popular media that their pain was preventable. For example, when riots broke out in Chile in mid-May, English-language news outlets reported the protests as a “clash with police over lockdown,” echoing the headlines of anti-lockdown protests in North America.

These headlines are, in fact, misleading. People took to the streets in the Santiago commune of El Bosque — where many work informally and now, not at all — over government inaction to feed the estimated 20,000 Chileans who are starving in quarantine. They have been on a strict lockdown since April, and while they are allowed to go grocery shopping, many cannot afford to do so and are now facing a dire food shortage.

Unfortunately, the situation in Chile is unsurprising. For the past six months, national protests against chronic economic inequality rocked Chile until the coronavirus outbreak brought them to a halt. The Chilean government, now with blood on their hands, must grapple with the knowledge that the protestors were right in their demands. However, even as COVID-19 cases in Chile dwindle, systemic change is unlikely. If the visible threat of respiratory illness disappears, privileged Chileans and government officials will likely continue as if everything is fine, while the residents of El Bosque will go on without adequate social services, and now, food and employment. The pandemic will only serve to expand the divide between rich and poor and aggravate already deplorable conditions in vulnerable communities.

Post-pandemic effects will not only be felt in Chile; in fact, they will be felt globally. Economists predict an impending economic crisis, a recession to which the 2008 Great Recession will pale in comparison. Already, 81% of the world’s workforce has seen their workplace partially or fully closed, and the restoration of employment will not be swift. When the pandemic hit, the first to lose their jobs were vulnerable workers; those who did not make an adequate salary for long enough to amass sufficient savings. They will likely remain unemployed and unable to financially recuperate as the economy contracts. Few will come out of the pandemic unscathed, and even fewer from the subsequent recession (except, perhaps, Jeff Bezos, who saw his net worth increase by $24 billion in the past two months), yet little has been done by world leaders to even acknowledge the impending economic collapse. The official narrative implies that there is an end in sight, if only we all remain in our homes and stay six feet apart. But for an estimated 3.9 billion people — the global total of people who may be living below the poverty line due to the economic impact of the coronavirus — life will never return to normal. The coronavirus has wreaked immeasurable havoc, much of which could have been prevented if it were not for the persistent discrimination against the most vulnerable from the very systems designed to protect them.

We have known for a long time that suffering from systemic inequality takes a physical toll. Socioeconomic status affects health, a fact that has never been clearer than during this global pandemic. Unfortunately, world leaders have done little to address the persistent disparities within their populations, and now the marginalized and poor are paying the price for their incompetence. This inaction cannot continue. World leaders must not only mobilize to combat COVID-19 but also address the systemic failings which have allowed the virus to further cripple the world’s most vulnerable communities. A post-pandemic world can either hold even greater socioeconomic disparity while the most privileged remain woefully ignorant, or we can take this opportunity to rebuild our nations in a way that leaves no one behind.

With any luck, there will be no return to normal.

Featured image courtesy of Mohini Dutta at the COVID Tracking Project at the Atlantic. This image is licensed under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-4.0.

Edited by Justine Coutu