Looking to the Future on Fiji’s 50th

Fiji has often been overlooked by the global community, but in the wake of the climate crisis, this tiny island nation has taken centre stage.

On October 10th, the island nation of Fiji will celebrate the 50th anniversary of its independence from the British Empire. While the Polynesian state is recognized worldwide as a tropical vacation destination, most people know very little about Fijian history, culture, or politics, mainly due to Fiji’s tiny population, small diaspora, and relative geographical remoteness. As we enter the next 50 years of an independent Fiji, amid the climate crisis, there is great value in educating ourselves more about Fiji’s past to better understand the country at present. Pacific island nations will comprise some of the populations that are most heavily affected by climate change, and Fiji is sure to play an outsized role in global politics in the coming decades.

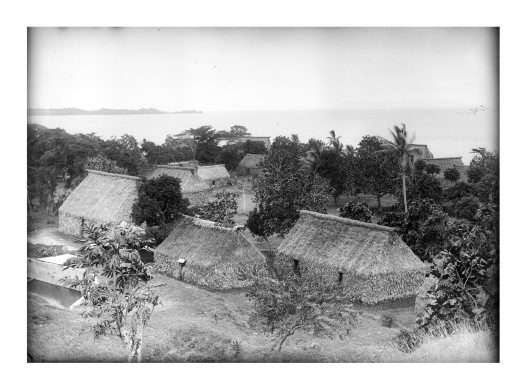

The group of islands now known as Fiji has been inhabited for over 3,000 years by a combination of Melanesian and Polynesian peoples. By the time European explorers reached Fiji, led by Abel Tasman in 1643, indigenous Fijians had a highly developed society. Early European inhabitants of Fiji included missionaries, who brought Christianity to the islands. In 1874, Fiji became an official crown colony of Great Britain, which it remained until post-war decolonization pressures pushed Fiji towards independence in the 1960s.

Divisions between ethnic Fijians and the Indo-Fijians, whose ancestors previously served as indentured workers on the island’s plantations, heavily influenced the country’s first constitution. In 1987, Lieutenant Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka staged a succession of coups, culminating in the creation of a new constitution that favoured ethnic Fijians. In the final years of the 20th century, the constitution was updated yet again, wherein Fiji was readmitted into the Commonwealth, and the Indo-Fijian Mahendra Chaudhry was elected prime minister.

The early 2000s were difficult years in Fiji. In 2000, following numerous bomb attacks organized by extremists, Prime Minister Chaudhry was deposed by yet another coup. In 2006, military leader Frank Bainimarama seized the role of the prime minister — which he has held ever since — through the country’s fourth coup in 19 years. Bainimarama quickly embarked on empowering military-supported presidents, creating a new and widely criticized constitution that protected Bainimarama’s military allies from coup-related legal action.

Fiji will continue to face political challenges as it enters its sixth decade of independence. Even more pressing, though, is its battle with climate change, which poses an existential threat to Fijians’ lives. As climate change leads to ever-increasing water temperatures, the mean global sea level continues to rise due to the thermally-induced expansion of water molecules and increased meltwater from glaciers and polar ice. Every inch of sea-level rise further endangers countries like Fiji where low-lying coastal communities are at risk of losing arable land and buildings to rapid erosion, flooding, and saltwater intrusion. These phenomena destroy peoples’ homes and food sources, in a country whose remoteness lends itself to infrequent shipments of outside goods. Tropical storms, which have always ravaged Pacific island nations, have recently begun to appear outside of their normal seasonal windows. These storms may be caused, at least in part, by climate change and have proven devastating for Fiji’s economy.

The seriousness of this issue is not lost on Prime Minister Bainimarama, who says he expects to relocate 40 Fijian villages to higher ground in the near future. The 2014 inland relocation of the village of Vunidogoloa was widely publicized as the first ever Fijian town to be moved because of climate change, but the future has many more such events in store. Relocation is not a perfect solution; land space on the islands is limited, leading to mixed results, with new village locations being subject to problems like landslides.

The governments of Fiji and other island nations have taken it upon themselves to become leaders in the global fight against climate change. Though they have relatively sparse financial resources, states like St. Lucia and the Maldives have managed to maximize their clout on the global stage through shows of interstate unity and diplomatic appeals to pathos. In particular, Fiji has stressed that all nations are “in the same canoe rising up against climate change.”

Indeed, it was a collection of island nations like Fiji that initially pushed for the development and adoption of the Paris Climate Agreement. Fiji was the first nation to ratify it formally in 2016. In 2018, this group of states was influential in the publishing of the IPCC Special Report, which warns of the consequences associated with a 1.5-degree rise in global temperatures. Fiji and its allies have strategically included local politicians, NGOs, and corporations in these negotiations, forcing dissenting delegations to speak face-to-face with those affected most by climate change, and whose fates will be most urgently affected by policymaking. By cooperating and presenting a united front, island nations threatened by rising sea levels and tropical storms are punching above their weight on the global policy front.

The Fiji Development Bank has partnered with the US Agency for International Aid (USAID) and is accredited with the UN’s Green Climate Fund, created to help developing countries, like Fiji, respond to the human and economic costs of climate change. The Fijian delegation acted as the president and official host of COP23 in 2017, directing the debate on international carbon emissions policies and climate change reduction goals. At COP23, island nations led by Fiji pushed to strengthen countries’ adherence to the Paris Agreement and pressured major polluters to stay on track in reducing emissions. Unfortunately, some of these efforts seem to have fallen on deaf ears — or no ears at all in the United States, which announced its intent to withdraw from the Paris Agreement earlier in 2017.

The next 50 years in world history will be defined by the impacts of climate change, and the actions of those seeking to combat it and maintain their livelihoods. After a tumultuous first five decades as an independent state rife with ethnic conflict and political instability, Fiji is emerging as one of the countries at the forefront of the climate crisis. The actions and leadership of Fiji and its Pacific neighbours will come to define and preempt the rest of the world’s response to the climate crisis.

Fijian dedication to surviving the climate crisis has been demonstrated by both its international diplomacy efforts and its internal policies. On the world stage, Fiji has become a global leader in climate policy, despite its small population and lack of resources. It has adopted a successful negotiation approach emphasizing inter-community reporting on the effects of climate change. Back at home, the Fijian government has committed to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and has adopted a multifaceted climate change plan with concrete policy recommendations while supporting its displaced communities. Fiji has talked the talk and will continue to walk the walk. It is now up to the rest of the world to listen and to follow behind.

Featured image: Men in traditional Fijian dress at the 2017 UN COP Climate Change Conference in Bonn, Germany. Photo by UNclimatechange is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Edited by Asher Laws