Afghanistan’s Gendered Healthcare System Re-Surfaces Amidst COVID-19

While the West sets out to reopen its economies, Afghanistan continues its attempt to mitigate the spread and impact of COVID-19. However, the country’s women face a particularly unique challenge: not only is the national economy and current medical infrastructure far from adequate for handling a health crisis, but the country’s social environment frequently puts women at a disadvantage.

Intense political instability due to the ongoing battle between the internationally recognized government and the Taliban insurgency continues to ravage and divide the country. In areas in which the Taliban maintains control, women are prohibited from getting an education or working outside the home as teachers or in other professions. Moreover, their mobility is severely restricted. Most relevant to the mitigation of COVID-19 is the historical taboo of male doctors treating female patients. With women being barred from education, and by extension, unqualified or simply prohibited from becoming doctors, women with health issues have essentially no avenue for treatment. These circumstances are especially dire in the context of the current COVID-19 crisis, but also expose a much deeper and ongoing problem of inaccessibility to healthcare along gendered lines.

The Taliban held national political authority between 1996 and 2001. For periods during their rule, women were explicitly prevented from accessing healthcare through official decrees, which barred them from treatment at hospitals in Afghanistan’s capital and forced female doctors out of practice. Even in emergency situations, such as war-related injuries like bullet wounds, women were turned away from hospitals on account of their gender. While these regulations have relaxed with the transition of political authority, women living in Taliban-controlled regions continue having difficulty accessing critical medical treatment, as it is presumed that the group continues to operate under provisions similar to those of their governing period.

The COVID-19 situation is both a health crisis and a political one, as Afghan authorities and Taliban leaders attempt to obtain political power and stability in the country. The healthcare system in Afghanistan is under attack, both by the Taliban’s political agenda and by a virus that knows no bounds. Women’s health has become a disposable pawn, with women’s human rights being violated in a social context that already disadvantages women, and routes for medical help having been destroyed amidst violent insurgency.

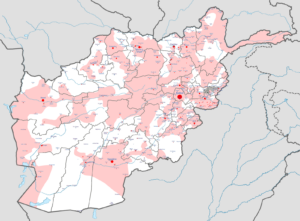

While the United States-led coalition initially dismantled Taliban strongholds in Afghanistan when they removed the Taliban from power in 2001, Taliban-controlled territories still remain. Healthcare in these areas is virtually nonexistent for these communities. In April of 2019, the Taliban banned the entry and operations of the Red Cross from their territory after the World Health Organization (WHO) pledged to vaccinate 9.3 million children against Polio in partnership with the organization, though the ban was lifted in September. Taliban leaders issued threats to both the Red Cross and WHO, alerting them that attacks were imminent if members of the organization were to enter Afghanistan as part of their campaign. Considering that attacks on the international community’s healthcare infrastructure are not uncommon in Afghanistan — one example being the deadly 2017 attack on an orthopedic center — these threats were taken seriously. As a result, standard healthcare is absent in many parts of Afghanistan, leaving people to work with inadequate systems that are scarcely available.

Even when healthcare is available, women are explicitly prohibited from accessing it. Under the Taliban, male doctors and nurses can only touch female patients above their clothing. This law has severe consequences for women’s health, especially reproductive health, which often requires invasive yet critical examinations. These constraints on reproductive health have led to death rates of up to 6500 women dying per year during childbirth. Other sources claim the rate is much higher. The Red Cross and other interim medical institutions are allowed to work in Taliban-controlled territory with the group’s approval, but they must adhere to Taliban regulations, rendering doctors powerless when it comes to women’s health operations that conflict with Taliban doctrine. Historically, Taliban militants have been stationed in hospitals or other medical locations to ensure that operations and examinations are done in accordance with their rules, and they are given the green light to intercept any activity contrary to said rules.

The Taliban has taken other measures to dismantle healthcare, both in an effort to continue marginalizing women within the system and to undermine the legitimacy and strength of the internationally-recognized Afghan authorities. In 2019, 192 healthcare facilities were closed down after the Taliban initiated attacks. Of these, only 34 have re-opened. These closures and healthcare constraints will foster the spread of COVID-19.

The Taliban may see this pandemic as an opportunity to gain political legitimacy. A logical attempt at exploiting COVID-19 for this purpose might entail an increased investment in healthcare and its requirements. Yet recent comments suggest that the Taliban’s manifestation of this investment would simply be a refrain from medical infrastructure bombings, allowing sites of healthcare to exist in the first place. Notably, Taliban spokesman Suhail Shaheen remarked that the group “assures all international health organizations and WHO of its readiness to cooperate and coordinate with them in combating the Coronavirus.” However, this cooperation has yet to extend to any meaningful slackening of the regulations surrounding women’s accessibility to healthcare.

An Afghan woman living in a Taliban-controlled region of Northern Afghanistan pondered, “Who will test the women?” when the single health clinic in her village was staffed with only male doctors. Despite the Taliban’s pledge — on paper — to cooperate with medical authorities to stop the virus, they must recognize that the virus is not limited by gender. Slowing the spread of COVID-19 requires equal treatment of all its victims.

Featured image: Women roaming the streets of Afghanistan wearing the burqa, which is mandated by the Taliban. “Women Wearing Burka in Afghanistan,” by the U.S. Air Force, is licensed in the public domain.

Edited by Nina Russell