Thank Slavery For The Second Amendment

“A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed” – The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution.

One of the most common defenses of the Second Amendment to the United States Constitution rests in the assertion that the people should have the right to bear arms in order to resist a tyrannical government. Asked what a tyrannical government actually looks like, some will explain that a government becomes tyrannical when it restricts one’s civil liberties, such as one’s freedom of speech and right to peaceably assemble. Yet few are calling for an armed insurrection against the Trump administration for its assaults on Americans’ civil liberties. After all, many of those protesting against systemic racism and police brutality are probably opposed to an unrestricted interpretation of the Second Amendment, not least because it has historically been invoked by racists to justify the killing of unarmed African Americans.

So when is a government considered tyrannical, and when does the Second Amendment become a necessary safeguard against government transgression? If someone had asked some of the founders, they might have said, “abolition.”

It’s not emphasized in history textbooks enough, but the Second Amendment was included in the Bill of Rights, at least in part, to placate plantation-dominated states in the South, so that slave owners could protect themselves from slave revolts and abolitionists by controlling their own state militias. People have only been misled into thinking otherwise because of a fatal misreading of history and a pernicious disregard for grammatical logic.

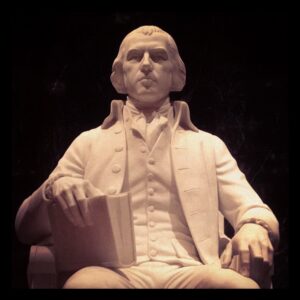

For starters, the question of states’ authority over their militias, not individual gun ownership rights, is at the heart of the Second Amendment. In June 1788, James Madison, one of the principal drafters of the Constitution and a future US President, made his case for ratification before the Virginia state convention. By then, eight of the nine states required to approve the Constitution had ratified it. Because New York, Rhode Island, North Carolina, and New Hampshire leaned anti-federalist (opposed to strengthening the central government), and did not seem likely to ratify it, all hope rested with Virginia. But it quickly became clear that Madison had made a dangerous oversight: he had inadvertently threatened the institution of slavery.

Slavery found its champions in Patrick Henry, the governor of Virginia and the colonies’ most renowned orator, as well as in George Mason, the intellectual leader of the anti-federalists. They railed against the proposed Constitution, arguing that its original wording, without the later addition of a Bill of Rights, implied that the federal government would be able to control a state’s militias without the state’s consent. This posed two problems for slave states. On the one hand, if the United States went to war and levied state militias, it would leave the southern states at the mercy of slave revolts. In some parts of the South, particularly eastern Virginia, white inhabitants were significantly outnumbered by their enslaved counterparts, and state militias were considered necessary to terrorize the slaves into submission. On the other hand, without explicitly extending the right to organize, arm, and discipline militias to the states themselves, the federal government might have been empowered to subvert the slave system by disarming the southern state militias. To this criticism, Madison argued that the states’ right to regulate their own militias was “concurrent” with that of the federal government. Nevertheless, Henry and Mason insisted that this was not the case, and nearly prevented Virginia from ratifying the Constitution.

Fear of Black people compelled Henry and Mason to resist the Constitution. And that fear defined the Southern cultural milieu that raised them: Southern colonists were habitually afraid of their human chattel, always fearful that enslaved African Americans would turn against them unless they were violently suppressed at every moment. Such fears were stoked by the Stono Revolt in South Carolina in 1739, after which state militias were increasingly used as slave patrols to subdue and preempt unrest, regularly inspecting slave quarters on plantations to search for arms and ammunition. Indeed, during the American Revolution, the southern states committed far fewer militias to the cause than their northern counterparts, because they feared inviting slave insurrection at home.

That same anxiety dictated their deliberations on the Constitution in 1788. The concern that the northern states might have been empowered to curtail slavery was justified; for as Patrick Henry observed at the convention, “slavery is detested… the majority of Congress is to the North, and the slaves to the South.” In short, the “tyranny” they feared was a government controlled by northern abolitionists.

In the end, Virginia ratified the Constitution by a thin margin, and, unbeknownst to them, New Hampshire did the same. The Constitution was adopted, in spite of the concerns raised by Mason and Henry. Nevertheless, determined to secure slavery, Virginia proposed that Congress consider a declaration of 20 rights, including a right to bear arms, and 20 constitutional amendments, including one empowering states to arm their militias if Congress did not.

When Madison was elected to Congress in the fall, he was careful to ensure that nothing in the Bill of Rights contradicted the authorities established in the main body of the Constitution. So, instead of explicitly stating that states had the right to arm militias, he made use of the fact that state militias traditionally required members to bring their own guns with them. The people (that is, the free, land-owning white people) would arm themselves and come to the states’ defense when mustered by the states, if the federal government did not raise them itself. And so, finally, control over the militias really was “concurrent” between the states and the federal government — as Madison had originally intended.

The Second Amendment, then, is a product of Madison’s political maneuvering. This inheritance has been misunderstood, because the militia clause is followed by a qualification: that the “people” have the right to bear arms. However, this clarification was only necessary because state militias enlisted free citizens who were required to bring their own firearms. Of course, it would have also eased states’ concerns about the tyranny of a standing army, the idea of which provoked images of red-clad British troops marching on colonial liberties. Still, this way of appeasing the antifederalists did not invite every American to overthrow a government that they perceived as tyrannical; it rested in the assumption that states would act as cohesive political units, giving states greater leverage in the national political arena.

Naysayers contend that the Second Amendment was less about regulating militias and instead necessarily about individual gun rights, because colonizing the western frontier posed many dangers, including resistance from Indigenous peoples. But they forget that frontiersmen were originally required to bear arms, as members of the militia, to combat Indigenous inhabitants of the land. They were, of course, regulated accordingly in preparation to fight them — following a brutal tradition that started with the first European settlements in the Americas.

An honest consideration of the historical context shows that the Second Amendment was intended to balance states’ rights and those of the new federal government — a particularly important issue to southern legislators who saw a strong central government as a threat to slavery. Yet that historical context has been ignored too often by lawmakers, and most troublingly, even by some of the Justices on the US Supreme Court. As the US reckons with its history of racial injustice and protesters topple statues that glorify racists, perhaps Americans should train their eyes on the Second Amendment that equally enshrines America’s history of violently asserted white supremacy.

This is the first installment of a two-part series by the author.

Featured Image: “Second Amendment” by Eli Christman is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Edited by Clariza-Isabel Castro