Family Ties: Sri Lankan Democracy in Peril

After Sri Lanka's election in August, the authoritarian Rajapaksa brothers now control both the presidency and parliament, spelling danger for the strength of the island's democracy.

Mahinda Rajapaksa in Russia by Alexander Nikiforov. Licensed under CC 3.0. No changes were made. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mahinda_Rajapaksa_in_Russia.jpg

Mahinda Rajapaksa in Russia by Alexander Nikiforov. Licensed under CC 3.0. No changes were made. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mahinda_Rajapaksa_in_Russia.jpg

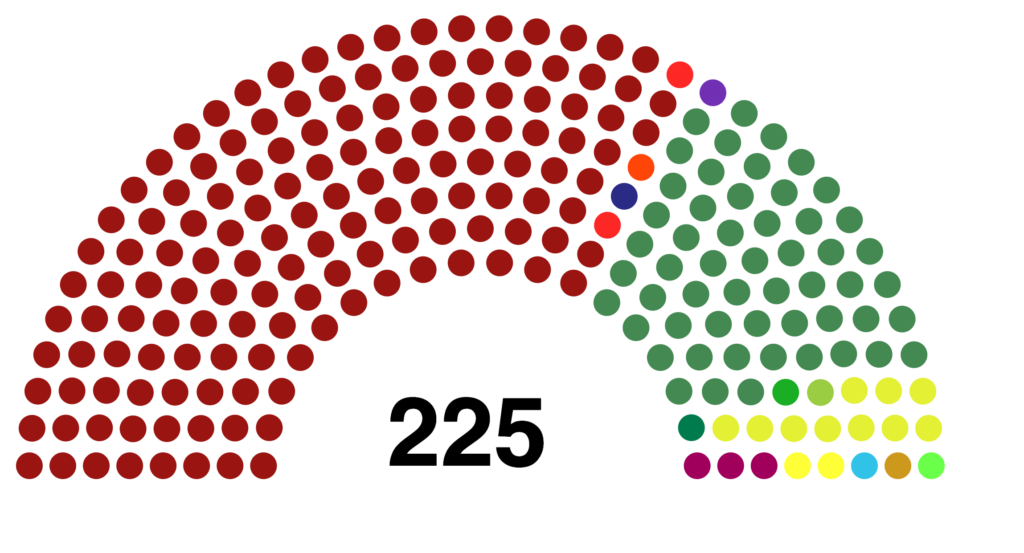

Having suffered a civil war and a constitutional crisis in the last fifteen years, Sri Lanka deserved an election that would bring stability to the island. Instead, on August 5, Mahinda Rajapaksa, an ardent nationalist belonging to a powerful political family, won an overwhelming majority in parliament and was elected prime minister. The Rajapaksa family’s reach throughout the Sri Lankan government is historic and pervasive. During the civil war, Mahinda’s brother Gotabaya, who is currently president, served as defence secretary, where he earned his reputation as a ruthless military officer. In that role, he also amassed numerous accusations of human rights violations that have yet to disappear. Mahinda, who was president during the civil war, garnered a similar reputation. The results of this election are particularly significant, seeing as the Rajapaksa family has gathered, through a coalition, a strong enough majority in parliament to alter the country’s laws and constitution with relative ease. Now, with the integrity of Sri Lankan democracy resting in the hands of these men, it is fitting to analyze their history of undermining it.

As politicians with substantial government experience, the Rajapaksas have a track record of struggling to uphold the country’s laws and stability. Mahinda Rajapaksa’s most recent spell as prime minister came in 2018, when then-President Sirisena unilaterally dissolved parliament and appointed him as a replacement, causing a constitutional crisis. Only a few weeks later, Rajapaksa was ousted after losing a non-confidence vote and the Supreme Court declaring his appointment unconstitutional. As illustrated by this tumultuous episode, Rajapaksa has shown little interest in compromising or finding common ground. His political career has also been characterized by controversial opinions and detrimental policies. In an interview with Time Magazine following the civil war, he falsely claimed that there had been “no civilian casualties” in the war’s final phase and, more importantly, confirmed that he did not support reconciliation with the island’s Tamil population, an ethnic minority. Rather than addressing the root causes of ethnic conflict in Sri Lanka, Rajapaksa’s policies are instead pushing the possibility of a long-term peace solution out of sight. In the northern, mostly Tamil-speaking province, his government supports “Sinhalisation,” which includes building military bases throughout the province, erecting monuments to Sinhala war heroes, and granting Sinhala businesses financial support to ensure Tamils are excluded from political and economic processes.

This project fits with Mahinda Rajapaksa’s broader strategy of quieting the grievances of minorities by inserting the military into economic and cultural spheres to maintain order. This strategy also includes restricting the free press and silencing any dissenters. In 2010, he began a censorship campaign that re-criminalized defamation and enabled him to suppress any anti-government journalism. Shortly before he was murdered, human rights activist and journalist Lasantha Wickrematunge claimed Rajapaksa wanted him dead. His fate was similar to that of many other dissenting journalists in the country. Accordingly, these authoritarian tendencies risk being amplified by a supermajority in parliament. As president ten years ago, Mahinda Rajapaksa amended the constitution by removing term limits, and his brother recently claimed he would loosen restrictions for elected officials by abolishing the 19th amendment, which dilutes the power of the presidency. With their hold on parliament and control of the presidency, there is almost no governmental resistance keeping the Rajapaksas from amending the constitution to serve their long-term political ambitions. It is clear that to them, the traditional checks and balances of government are simply unnecessary obstacles to propagating an authoritarian vision throughout Sri Lanka.

Without any domestic opposition, the most likely resistance to these authoritarian developments will come from foreign democracies. To avoid possible reprimands from the international community, the Rajapaksas will need to maintain their strong relationships with powerful neighbours, specifically India and China. Consequently, Mahinda Rajapaksa promised to nurture his friendly relationship with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who has contributed to Sri Lankan COVID-19 relief efforts and shares the Rajapaksas’ nationalistic political outlook. Despite Sri Lanka’s close relationship with India, the country more often looks to Beijing for economic and military support. In light of this, both Rajapaksa brothers have claimed that they would maintain a neutral position between the United States and China, but given their close relationship with Beijing, this scenario seems unlikely. Indeed, the prime minister’s history with China is a controversial one. When he illegally seized power in 2019, Beijing quickly congratulated him. Later, when he asked for enormous loans to build a port, China provided them. When Mahinda Rajapaksa’s government needed military hardware to win the civil war, China supplied it. And finally, when the Rajapaksa brothers were accused of violating human rights by the international community, China cleared their names.

Moreover, the Rajapaksas oppose US military bases on the island and distrust American influence in general. With both economic debts to Beijing and a personal aversion towards Washington, it is nearly impossible for the Sri Lankan government to remain neutral in any Chinese-American conflict, and the implications of this reality are significant. Chinese President Xi Jinping has clear motivations to grow the Sri Lankan debt and the island is ripe to expand the Belt and Road Initiative. To date, Chinese investment has had a negative impact on Sri Lankan democracy, especially in terms of human rights and labour laws. With closer ties to Beijing, the Rajapaksas will have access to significant military power, which, in turn, will allow them to keep up their pattern of silencing journalists and covering up human rights abuses. In short, without the international community reprimanding human rights abuses in Sri Lanka, no one will.

At home and abroad, the Rajapaksas are well situated to enact whichever policies they please. The new parliament’s powers are significant and as seen under previous governments, civilian opposition in Sri Lanka is quickly quashed. As a result, they have both the means and motivation to further their own interests at the expense of their citizens. The declining influence of Western democracies in comparison to the governments of Modi and Xi spell danger for basic civil rights and liberties in the region. Ultimately, the Rajapaksas are openly authoritarian politicians, whose interests and political track record do not align with protecting the integrity of Sri Lankan democracy.

Featured image: “Mahinda Rajapaksa in Russia” by Alexander Nikiforov is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Edited by Chino Ramirez.