The Paradox of Universal Housing in Singapore

Few countries can show off a success story nearly as remarkable as that of Singapore. Located at the tip of the Malaysian peninsula, the island-state features some of the highest levels of socio-economic development, ranking ninth on the Human Development Index (HDI) and recording the third-highest Gross Domestic Product per capita in Purchasing Power Parity in 2020, only 55 years after its independence from Malaysia. Remarkable economic growth was complemented by outstanding social policy efforts, the most successful of which is the Universal Housing Policy (UHP). However, the COVID-19 pandemic has spotlighted several cracks in the policy, particularly its inability to maintain ethnic cohesion and reduce disparity among the city’s many racial groups.

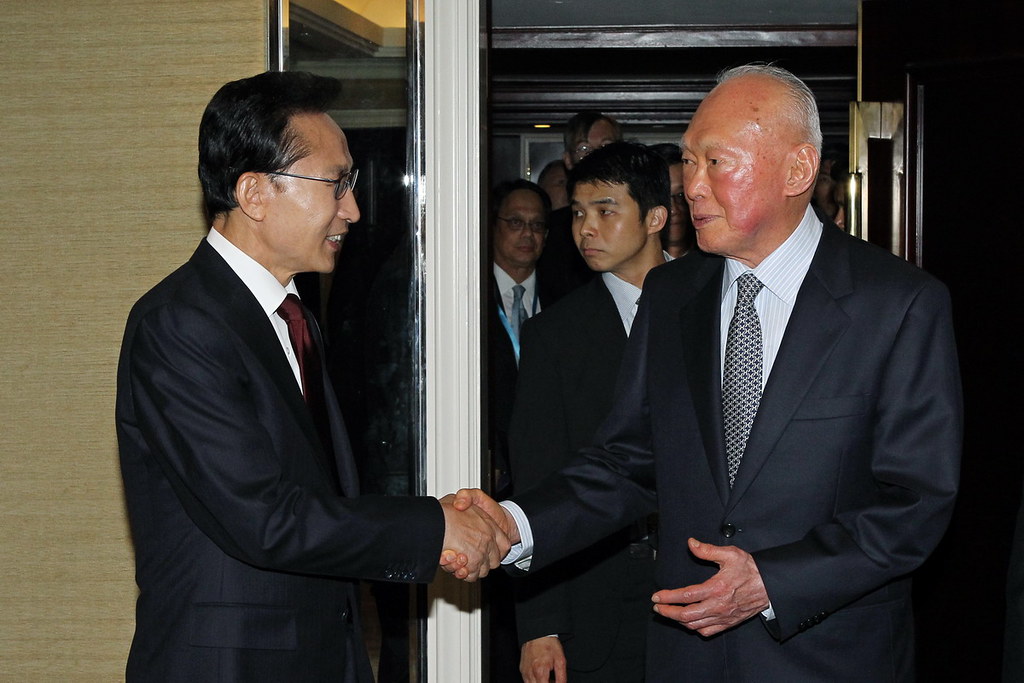

Post-independence problems and the Housing and Development Board

Singapore’s UHP is the brainchild of the independent city-state’s first Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew. At the dawn of its expulsion from Malaysia in August 1965, Singapore found itself in a potentially dire situation. Much like its neighbour-state, Singapore has an ethnically and culturally diverse citizenry, with 76 per cent being Chinese, along with 15 per cent Malays, 7.5 per cent Indians, and other groups making up the remaining 1.5 per cent. The question of ethnic cohabitation proved to be a contentious issue in neighbouring Malaysia, which went as far as to trigger large-scale riots on May 13, 1969 following the electoral win of the Chinese-majority opposition Democratic Action Party (DAP). Moreover, Singapore faced a dramatic housing shortage crisis, increasing the potential for violent clashes like in Malaysia.

Lee Kuan Yew’s response to both problems was the establishment of the Housing and Development Board (HDB) in February 1960. The HDB built several hundreds of thousands of low-cost, state-owned housing units which were rented out to citizens only (although permanent residents whose immediate family included at least one citizen were also entitled to a housing unit). Additionally, Singaporeans could use the existing Central Provident Fund (CPF) — a comprehensive social security system allowing citizens and permanent residents to save funds for retirement and healthcare — to help them finance a state-owned house. In 1989, these state-owned dwellings begun applying the Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP), placing a minimum quota on ethnic groups inhabiting the facilities. Due to the city-state’s demography, initial quotas sought to facilitate the moving of non-Chinese populations into HDB dwellings.

Both the UHP and EIP proved to be an adequate and long-lasting response to the housing shortage crisis that once imperilled the city; Today, nearly 80% of Singaporeans live in state-owned dwellings. At first glance, this policy appears to borrow more from the planned economy tradition of centralized governments like the former Soviet Union, rather than the US-backed neoliberal governance style. However, Singapore’s home-ownership rate of 91 per cent ranks #1 in the world. Additionally, the EIP helped ease the risk for inter-ethnic rivalries which had marred Malaysia two decades ago, and is still pervasive today. In this sense, the UHP owes its success to a savvy mix of modern capitalism and state-planned socialism, which has been Singapore’s home recipe for many of their public policy successes. Unfortunately, the current pandemic highlighted the unforeseen limitations of Singapore’s most successful social initiative.

A success for ethnic integration?

COVID-19 disturbed Singapore’s domestic politics, much like the rest of the world. In April earlier this year, the Singapore Ministry of Health reported that the situation was critical, with an average of 600 new COVID-19 cases per day, peaking at 1426 on April 20 alone. This was a stark contrast to the January average of 50 daily cases.

Poor housing facilities for foreign workers were partly responsible for the surge in cases. In fact, considering that the UHP’s privileges are strictly reserved for citizens and occasionally permanent residents, foreign workers are completely excluded from the policy. Despite its extensive ambition, the UHP excluded nearly a quarter (1.3 million individuals) of the population.

Since the government mandates employers to provide accommodation for foreign employees, Ministry of Manpower (MOM) dormitories have been a key housing solution for many low-wage foreign workers, the majority of whom are from Bangladesh, India, or China. These dorms represent an ugly contrast to the HDB-administered dwellings — the living conditions of these units are poor, and are relegated to areas far from the vibrant downtown neighbourhoods where civic facilities are easily accessible. While purpose-built dormitories providing amenities like minimarts, laundries, and gyms have been on the rise for the past few years, most of the current existing dorms are low-cost dwellings, and are oftentimes converted factories or temporary quarters where the living conditions are deplorable.

These facilities invited much criticism at times for allowing up to 20 workers to share a room pre-pandemic. Human rights advocates also denounced other inhumane conditions, such as the lack of clean water. In late March, a Singapore-based Southeast Asian migrant rights group, Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2), warned of potential virus clusters in the city’s most poorly administered and unhygienic dorms. It took a nationwide lockdown to bring this nightmare scenario to reality; Since April, transient workers formed the overwhelming majority of COVID-19 patients in Singapore. This surge in cases undermined Singapore’s early successes at detecting and preventing major outbreaks, and reminded the government of the dismal extent of ethnic integration in the city.

Moving forward with universal housing

Singapore owes much of its infrastructural development to South and Southeast Asian migrant workers, who significantly contribute to the city-state’s GDP. Such claims are far from being unfounded; the South Asian diaspora is associated with the buildup of major economic hubs in Asia — including the vibrant metropolis of Dubai in the United Arab Emirates — despite government failure to adequately recognize their labour.

With the number of cases steadily decreasing, uncertainty looms over the fate of foreign workers in Singapore. Admittedly, the UHP is undoubtedly one of the city’s biggest social policy achievements, but the current health crisis shows that outstanding social policy does not necessarily prepare a country for a pandemic.

Ultimately, the approach to universal housing must be incrementally changed. Singapore cannot remain complacent in the striking paradox that weds one of the most successful universal housing policies in the world with an ever-growing housing crisis for migrant workers in the city. Early efforts from the MOM must be noted, including the decision on November 6, 2020, to set up a task force to increase mental health support for foreign workers in their dormitories.

Nonetheless, it is difficult to envision an improvement in the emotional well-being of workers if their basic housing situations are not adequately addressed vis-à-vis the current health crisis. While the MOM announced in June 2020 that new dorms would be built by the end of the year, Siagapore’s land scarcity lends uncertainty to this promise. The current government must continue to prioritize battling the pandemic, however, it cannot come at the detriment of Singapore’s foreign workers’ living conditions.

Featured image: Singapore skyline by Jia Le under Unsplash License. No changes made.

Edited by Sajneet Mangat