Justice Department vs Google: the Politics of Antitrust in the United States

The lawsuit against Google signifies rising tension between the Federal government and Big Tech. Passing sweeping antitrust bills will not be easy for the Biden administration, but antitrust is certainly on the agenda.

The threat Big Tech poses to the economy is a ubiquitous talking point; across different geographical regions, political views and generations, most Americans agree that companies like Apple and Google are too powerful. Yet it was not until recently that industry monopolies reemerged as a political issue salient enough for the Department of Justice (DOJ) to file an antitrust lawsuit against Google in October 2020.

Antitrust laws were written for the express purpose of safeguarding average consumers against giant companies by stopping abuses of power in economic markets; in practice, they exist to foster competition. In a competitive market with many players, a seller cannot offer unfavourable prices to consumers without losing business. Prices must be agreed upon by both the consumer and producer — in doing so, the market ensures that consumers are not exploited. Individual consumers also benefit from innovation encouraged by competition, as firms are forced to “continually strive to improve their goods and services,” without substantially increasing their price. Why, if antitrust laws are so beneficial for consumers, did their use decline in the late 20th century?

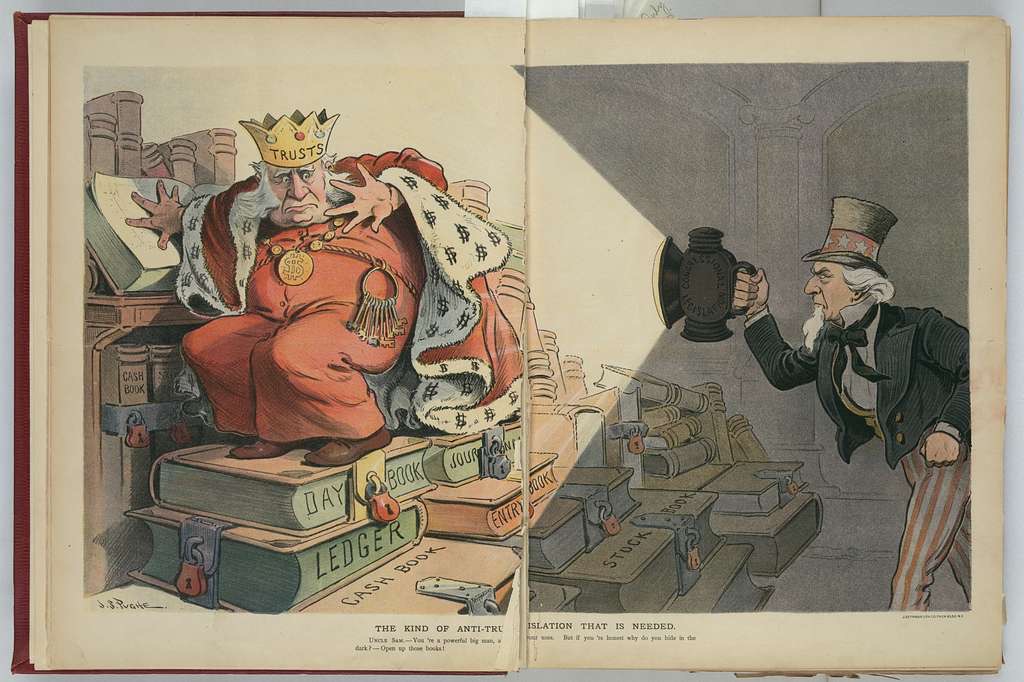

Antitrust’s use in the 19th and 20th centuries fluctuated greatly. Due to monopolies existing in the rail, oil and steel industries, antitrust laws were passed, like the Sherman Act of 1890 which prohibits firms from striking deals that limit competition, and agencies established to enforce them, like the Federal Trade Commission (FTC). After the World Wars, when American attention turned inwards again, support for antitrust laws swelled; economist F.A. Hayek endorsed them as necessary to create socially optimal economic conditions, specifying that “a carefully thought-out legal framework is required.” However, beginning in the 1970s, public support for antitrust enforcement waned as enthusiasm for self-correcting markets grew. In short, when monopolies were perceived as charging exorbitant prices, antitrust was strongly enforced. When that view’s popularity declined, so too did antitrust enforcement.

But in the 21st century, the impacts of monopolies on consumers are not limited to prices, as they now affect industry development and user privacy, which explains recent calls for stricter antitrust regulation and the lawsuit against Google. In light of this, Members of Congress investigated tech giants for over a year, an initiative culminating in a report urging for stricter regulation to be imposed on companies like Amazon, Facebook, and Google. This investigation led to the DOJ’s lawsuit against Google, in which it accuses the company of violating antitrust laws.

The lawsuit’s central complaint is that Google’s dominance of search functions and search advertising is unfair. The DOJ alleges that some of its practices are anticompetitive, including payments made to Apple to secure its status as the default search engine on Apple devices and the pre-downloading of Google apps onto Android devices. For consumers, however, the harmful effects of Google’s actions are barely noticeable. As the company argues, its search engine is free and already on consumers’ devices, making it affordable and convenient for them to use. This argument is similar to the one made by Standard Oil in 1911: it supposedly lowered prices to benefit its consumers, but by the same token put other firms out of business and subsequently dominated the market. Antitrust lawyers agree that it’s challenging for consumers to notice how Google’s monopoly affects them, since the true harm lies in preventing future small businesses from growing, innovating, and competing, which would eventually produce better outcomes for consumers. Furthermore, because of its dominant market share, users often feel forced to accept Google’s terms and conditions, which may infringe on their rights. For instance, when users click “join,” they relinquish their right to go to court against the site, even in cases where it might be justified. Individuals depend on firms like Google and Facebook daily for their jobs and social networks, meaning that many cannot avoid agreeing to the terms and conditions. Google’s use of personal data does indeed inflict damage on users — not necessarily in monetary terms, but by limiting the quality of goods they are offered and infringing on their ability to say “no.”

The implications of the lawsuit are still unknown. While this case will spend years in court, Google is not the only one being prosecuted; any small victory for the DOJ will likely be applied to other Big Tech firms. In addition, over 40 states plan to file a similar suit against Facebook, and the FTC could present a related complaint. Furthermore, the volume of lawsuits against Big Tech will likely increase under the Biden administration.

Democrats and Republicans view antitrust regulation differently. Recently, Democrats have broadened the scope of antitrust, claiming that modern tech monopolies decrease social welfare in ways that go beyond price, whereas Republicans are hesitant to expand its definition. In the past, antitrust focused narrowly on the consumer welfare standard, strictly emphasizing the dangers of price increases. However, this definition does not account for monopolies’ role in blocking entrepreneurship, controlling advertising, and shutting down small businesses.

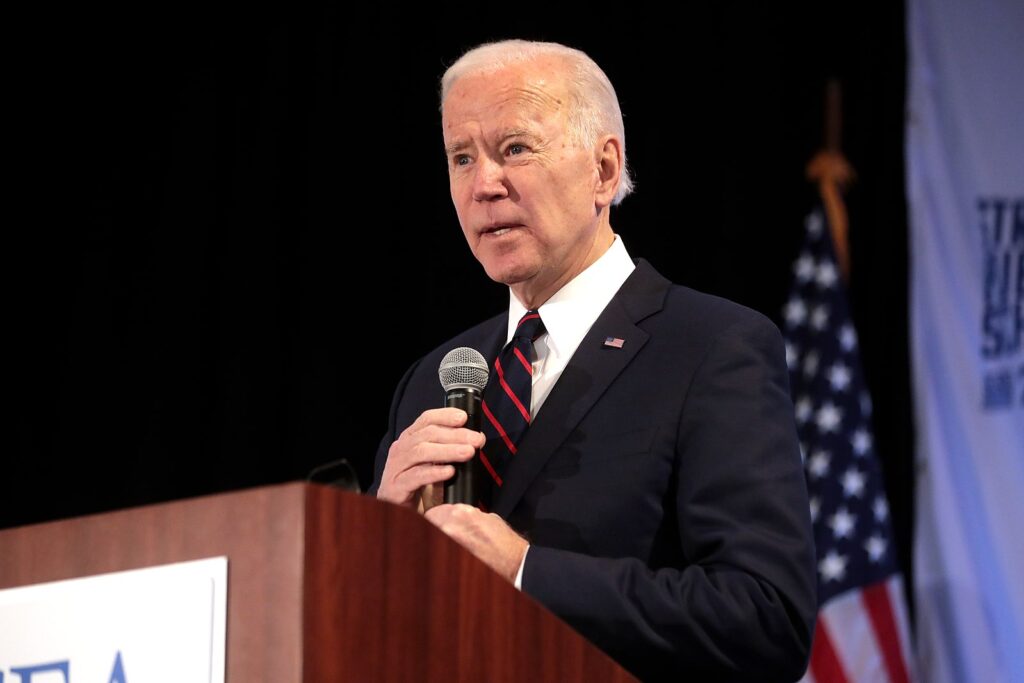

The Biden administration will likely not pursue as aggressive of an antitrust policy as some members of the party would hope. Instead, it seems antitrust will be an avenue for building bipartisan bridges, albeit at the cost of strong action. House representatives David Cicilline (D) and Ken Buck (R) plan to write the legislation together, but antitrust experts, like former deputy director of the FTC Sean Royall and Georgetown University professor David Vladeck, do not expect such legislation to bring comprehensive changes. In the Senate, the tone is similar. Even if the President-elect does seek aggressive regulation, enacting it will depend on the Senate and its extremely narrow margins. Should Republicans maintain control, hopes of sweeping reform will stall. Furthermore, even though Biden will take office in 2021, he will inherit an FTC with a Republican majority, the commissioner of which he cannot replace before 2023. In sum, standing in the way of aggressive antitrust regulation is a close Senate, a conservative FTC, and a political appetite for moderation.

While Biden’s team presumably will not start an antitrust revolution, it will likely trigger a leftward shift in regulation. With or without a Senate majority, Biden can expand the lawsuit against Google and block more mergers between competitors, echoing his work against a T-Mobile and Sprint merger during his time as Vice-President. The issue of social media regulation can also be dealt with: Biden promised to push for the revocation of Section 230, the law that shields tech companies from liability for the harmful content published on their platforms. Biden can also restore net-neutrality rules by repealing Trump’s Freedom Order, which slashed Obama-era regulations.

During the Biden administration, it appears there will be a balance between pushing whatever antitrust legislation possible, no matter how minor, through a divided Congress and using the power of the executive branch to enact larger reforms. Biden’s once-friendly relationship with tech companies and Silicon Valley has seemingly expired, and facing serious pressure from the progressive wing of his party, antitrust regulation is on the agenda, although it may not be a top priority. Whatever the result, antitrust plays a significant role in the denouement of the Biden campaign. Tackling bipartisan issues was a focal point of his campaign, as was rebuilding faith in government, both of which could be accomplished through competent antitrust regulation.

Edited by Sara Parker

Featured image: Google Food by brionv. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0