A Mari Usque Ad Mare: East-West Regionalism in Modern Canada

What does regionalism look like across Canada's provinces?

"Centennial Flame" by nic_r is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

"Centennial Flame" by nic_r is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

I am a Western Canadian. That’s a fact I live my life by almost out of choice at this point. I’ve been living in Montreal for about as long as I ever lived in Calgary, and as those who know me will tell you, I’ve spent my time in plenty of different places. Despite that, I’m proud to be Canadian, and I’m proud to be a Westerner —but nowadays, those two statements carry very different meanings. As a Canadian, I’ve listened to Stan Rogers folk tunes about leaving the East to work in the West. As a Westerner, I recall family dinners narrated by the likes of Ian Tyson and Hank Williams, as I shared the table with relatives who have never been East.

On the other hand, I know plenty of Easterners who see no point in travelling to the West. It’s not uncommon for someone to stay where they’re comfortable, but why is it that Canada can be split in half by citizens who have yet to cross the centre line? More importantly, what are the consequences?

In the United States, North-South regionalism came to a head during the American Civil War — the deadliest war in its history — that killed 620,000 Americans. Even in a nation that claims to be the hallmark of freedom, such division can be fatal. The Civil War was motivated by disagreements over human enslavement, which Canada has not struggled with for centuries. Still, Canadian East-West regionalism is nonetheless readily visible.

Canada is an incredibly diverse nation. For nearly a century, Canadians largely disapproved of the American melting-pot theory. Instead, we’ve preferred the idea of a “cultural mosaic,” a term adapted from John Murray Gibbon’s 1938 book, “The Canadian Mosaic.” This concept encourages Canada’s many demographics to retain their cultural ties and build on one another to create Canadian identity. The policy adaptation of the idea — “multiculturalism” — will celebrate 50 years in 2021.

East-West divisions in Canada began with geography before people and politics were factors, with the Rocky Mountains. The Rockies’ rain shadow led to the diverse ecological and economic systems that span Canada today. Since the first landing of human beings in North America 13,000 years ago, the Indigenous peoples caught in this rain shadow preferred a nomadic lifestyle that helped them thrive on the dry, golden flats of Canada’s prairies. Meanwhile, Indigenous peoples out East (and in British Columbia on the far side of the mountains) more rapidly became sedentary. Even before European economies had reached North America, two distinct ways of life had been established in either half of the region based on the Rocky Mountains’ rain shadow. With sedentary agricultural life being more conducive to European settlement in the 16th century, Western lands were mainly employed for fur trading rather than permanent settlement until 1812.

In many ways, the delayed development of the West (again, excluding British Columbia) still exists. The less diversified economies of Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta suffer shocks disproportionately, as their economies rely almost entirely on agriculture and natural resources, namely oil. Accordingly, the industrial development of the prairies pales in comparison to the industrial hubs of the East: Toronto, Montreal, and Quebec City, to name a few. Compared to the agrarian West, the East (beginning at the Manitoba-Ontario border) was home to about 26 of Canada’s 38 million inhabitants, and 67 of Canada’s 100 largest urban centres were in Eastern provinces as of late 2020.

Beginning with the American loyalist immigration at the end of the 18th century, the West developed a political identity as a conservative stronghold: a logical attitude in a region so different and distant from Ottawa. The subsequent sentiment of “western alienation,” then, is the product of mutual misunderstanding.

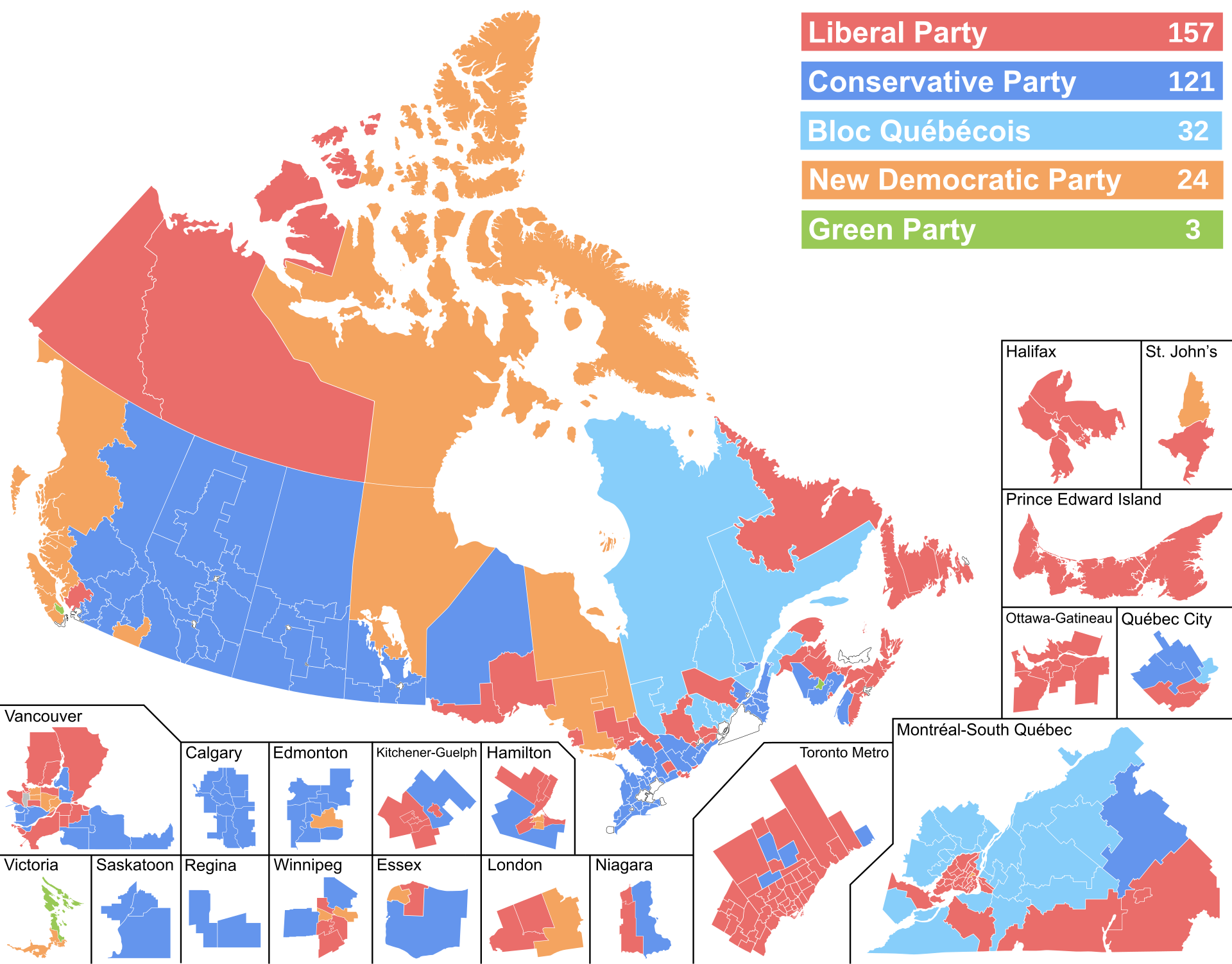

Western Canadians are politically disadvantaged in terms of representation in Ottawa. The Canadian House of Commons is a group of 338 Members of Parliament who hail from districts of equal population. Due to the lower population of the Western provinces, larger areas have less sway and receive less federal attention, disproportionality that further contributes to the sentiment of western alienation. And with a flight from Victoria to Ottawa ranging from 6 to 14 hours, it can be easy to feel cut off even as an elected official. It should be noted that Westerners sometimes enjoy greater federal representation on the individual level due to the lower citizen-representative ratio. Still, Alberta has the highest electoral quotient in the country, while only sending 34 Members of Parliament to Ottawa.

Now that we know what East-West regionalism looks like in Canada, what are its causes? “Wexit,” as silly of a word as it is, stole the spotlight in 2019. The cries of secession from Saskatchewan and Alberta occurred as tensions with the federal government were riding high and oil prices low. The West’s pipelines required to keep its oil industry-relevant were being tabled by Ottawa, leaving entire sectors to feel ignored. Pro- and anti-pipeline protesters rallied across the nation, expanding the issue that began in economics into civil and indigenous rights. Before COVID hit, this was Canada’s hot button issue. So the burning question: is Wexit a possibility? Would Canada need to imagine assuming a new shape as provincial borders become international borders? Are we hurtling toward a civil war for the fate of the north? Likely not.

While reading this article, you may have noticed that East and West Canada are two distinct regions of the same nation. Through years of cultural, economic, and political differences, the Ontario-Manitoba border has served as a line in the sand between the two halves of the country. Canadian identity has assuredly developed around it: I say that from experience. However, as a political science and economics student, and a man from a Western family studying at an Eastern university, I don’t see an irreparable divide that will threaten to drive Canada apart or plunge it into war. Instead, I see two pieces of a plurality of cultures and identities: mere fragments of the stained glass artwork we call Canada. East and West are not the only categories into which we sort Canadians. There are countless languages, heritages, and lifestyles supported through the democratic tolerance that we are lucky enough to enjoy here. As Thomas D’Arcy McGee cried during the Confederation debates, “When I can hear our young [people] say as proudly, our federation, or our country, or our kingdom, as the young [people] of other countries speak of their own, I shall have then less apprehension for us.”

Featured Image: Centennial Flame burning on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. “Centennial Flame” by nic_r is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Edited by Luca Brown