Nostalgia Nationalism: Twisting the Image of the Past for the Present

The origins of the word “nostalgia” lie in the combination of the Greek words “nostos,” meaning homecoming, and “algos,” meaning ache. Initially used in the late 1600s to describe the homesickness that Swiss soldiers felt when fighting away from home, nostalgia was regarded as a medical problem and was commonly diagnosed among slaves, soldiers, and labourers. While then, the term was used to denote a state of risky, clouded judgement, today the term is often used in a much lighter sense. However, the dangers of letting nostalgia mislead one’s historical judgement remain, so much so that playing on nostalgia has become a viable political strategy. By invoking the propaganda of the past and contrasting it with imagery of the present, political parties can prey on individuals’ sense of nostalgia in order to associate themselves with a counterculture against mainstream political movements, thereby indicating a “return to tradition.” While today’s difficulties and a yearning for the past are interconnected, conservative parties have somewhat successfully capitalized off of the resurgence in nationalist thought over the past several years. Calling on people to fondly remember the past serves two purposes. First, given the prevalence of rhetoric ‘good ol’ days’ rhetoric, politically-motivated individuals or groups can very easily ignore legitimate explanations for countries’ issues, such as wages, education, or crime. Second, nostalgia for a past in which the human rights of marginalized groups were ignored can be used to stir xenophobic or sexist sentiments.

Anemoia and the empires of the old world

“Anemoia” is defined as “nostalgia for a time you’ve never known”; While often used to describe the odd feeling when you look at old pictures, nationalist parties have manipulated the sentiment to encourage devotion towards old empires and regimes. Turkey perhaps provides one of the most prominent breeding grounds for this kind of conservative, traditional ideology. Aptly titled Neo-Ottomanism, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has used Ottoman imagery and history as a selling point and inspiration for his policies. He has played off prevalent conceptions of the fall of the Ottoman Empire as a betrayal by Europe, which carved up Ottoman territory among themselves through various treaties. In fact, the history of the Turkish republic was not pro-Ottoman; politically, the creation of modern Turkey was a movement built around secularism. It was intended to be a transformation of the Ottoman Empire into a modern nation-state involving reformations in all forms of government, culture, and life, through drawing on Western values. In a country like Turkey, where the art, religion, food, and architecture essentially create an open-air museum for the Ottoman Empire, it is difficult for the Turkish to escape their heritage. From this vantage point, it becomes easy for leading parties and political movements to invoke nationalism and form a rallying cry around this imagery. The two main culprits behind this style of nationalist behaviour are the leading Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP). A very recent but blatant instance of Neo-Ottomanism was Erdoğan’s decision to turn the Hagia Sophia back into a Mosque after it was stripped of its museum status by a state court.

Virtually every European country exists in a context similar to Turkey’s, wherein citizens are surrounded by landmarks, traditions, and relics from decades, centuries or even millennia ago. Italy, for example, has seen a resurgence in fascism wherein politicians need only look back to World War II and the rise of Mussolini for a turbulent era to draw on. The Roman empire and its remnant architecture has also been subject to exploitation by fascists and nationalists in the country. In Nordic countries like Sweden, far-right movements have linked increases in immigrants to the country’s problems, positing ethnic homogeneity as a solution. These examples show that if not taught with nuance or properly analyzed, any part of a nation’s history, be it architecture, religion or past leaders, can be selectively exploited for political gains.

Echoes of the Cold War

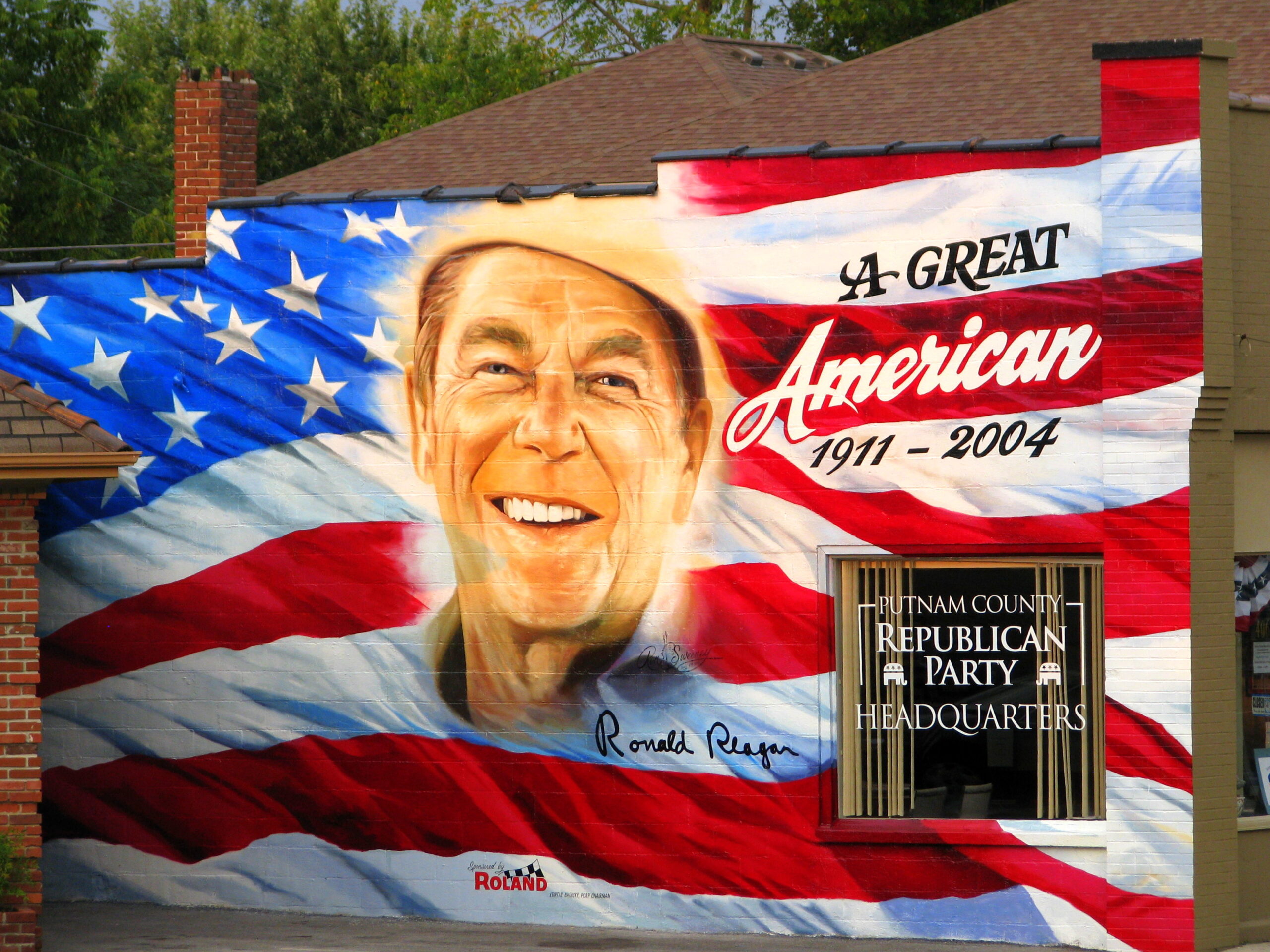

Recent events have demonstrated that a country doesn’t need an esoteric imperial legacy to draw from to use nostalgia as a political tool. In America and Russia, too, politicians have not hesitated to wield images of the past for political gain. In the US, Donald Trump’s campaign slogan, “Make America Great Again,” attempts to create a rose-tinted vision of America’s past. Despite the fact that the slogan does not define any period (though it originates from the Reagan era), the strength of “Make America Great Again” lies in the audience it can target. If a Trump supporter believes that America was great in the past, whether that be in the 1950s or 1990s, this slogan will invoke nostalgia from that period. The statement “Make America Great Again” implies that America was greater at a point in the past and that modern leadership has driven the country away from that time. This idea resonates strongly with a significant part of the American population. Studies show that seven out of ten Trump supporters believe that American society has gotten worse since the 1950s, with 51 per cent of the general population feeling that the American way of life has changed for the worse since then. This inevitably leads to skewed views of a nation’s situation by the citizens and individuals on which democracy relies.

In Russia there is a considerable population that is nostalgic for the Soviet Union, so when President Vladimir Putin makes statements calling the collapse of the Soviet Union “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.” it should come as a shock to no one. And regardless of how one views the state of Russian democracy, it is vital for Putin to appeal to that demographic. From the beginning of his political career, Putin has set out to restore Russia’s greatness and has taken to altering historical narratives and educational curriculums to support that vision. This involves glorifying past times of prosperity, ignoring times of struggle, and consolidating the Soviet past into one unified Russian history in order to strengthen the bond between the nostalgia of the past and the government of the present. Soviet nostalgia has become a unique way to develop and forge a new Russian national identity following the collapse of the Soviet Union and to combat the regret and idealization that many Russians felt towards the previous period.

Nostalgia affects us all, and no matter one’s background, most have felt a longing for a certain past. Those feelings are a powerful tool that can be manipulated to rally people behind blind traditionalism at whatever cost. In trying to construct these pasts, politicians will do whatever it takes, from changing narratives to completely eliminating or altering the history taught in schools. It is important to make sure that individuals understand the exact nature of the past from all angles in order to prevent themselves from being susceptible to those who attempt to invoke a past era in service of today’s goals.

Featured image: “Roman empire” by Jae C. is licensed for use under CC BY 2.0

Edited by Nina Russell