The EU’s Deal With Libya’s Coast Guard: Funding the Continuation of the Global Refugee Crisis

Refugees attempting the Mediterranean crossing in January 2016.

Refugees attempting the Mediterranean crossing in January 2016.

Although Europe’s ongoing migrant crisis experienced a peak in 2015, the consequences of the pressure borne by European nations at the time — particularly by the Mediterranean countries who received a majority of asylum-seekers — are increasingly being felt today. In an attempt by the European Union (EU) to reduce migrant arrivals, a growing number of member states have begun adopting anti-immigration policies, with little regard for the migrants consequently affected. In the case of Libya, European countries recently signed an agreement with the Libyan Coast Guard (LCG), agreeing to provide financial and material support to the LCG in exchange for Libya taking on the responsibility of seizing and returning migrant boats leaving from their coast. This allows European nations to purposefully disregard the obligation they have to uphold international law, which states that they cannot return refugees “to a country where they face serious threats to their life or freedom,” as declared under the 1951 Refugee Convention. The core principle of nonrefoulement is thus technically respected since the signatory members are not those directly refusing refugees’ access to safety.

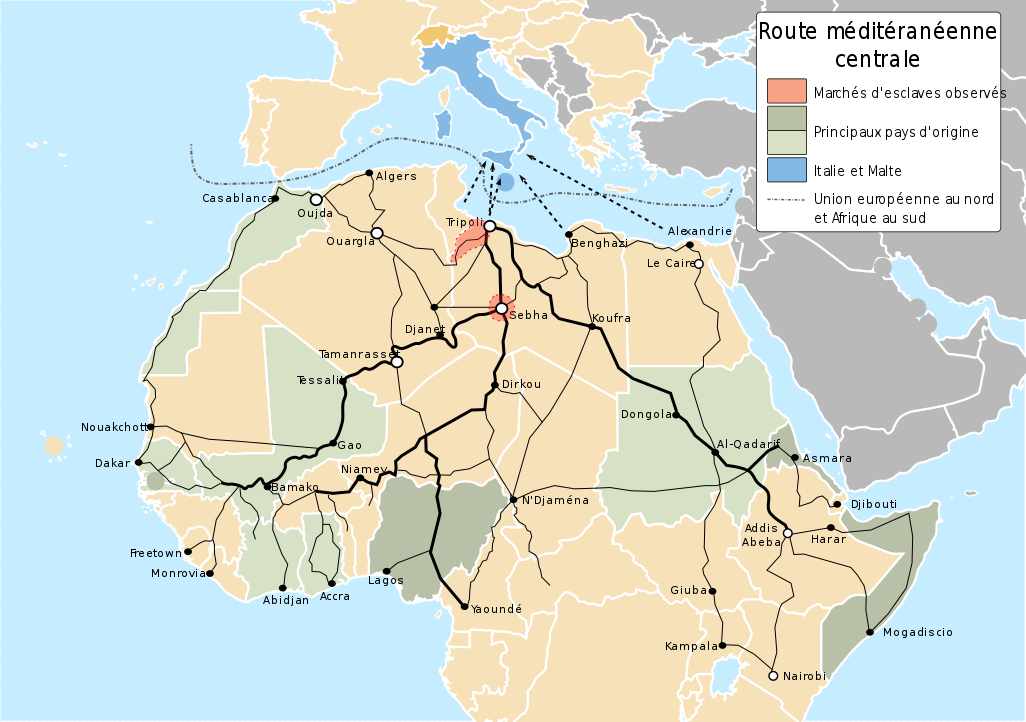

Since the fall of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi’s authoritarian regime in 2011, the country has faced worsening political instability. With no central government and rival militias dividing the nation, smuggling businesses based out of Libyan ports have thrived. The flow of migrants leaving for Europe through the central Mediterranean route — usually Libya to Italy — has risen drastically in past years. While all of Europe felt repercussions from the exceptionally high influx of migrants in 2015, seeing over 1.3 million arrivals from multiple war-torn countries in North Africa and the Middle East, Italy has been especially affected. Proximity to Northern Africa via the Mediterranean Sea has made it one of the most accessible European nations; as a result, Italy has continuously received between 120,000 to 180,000 migrants each year since, with numbers only dropping after their agreement with the LCG in late 2017. At this point, with the EU refusing to help migrants and removing most of their naval forces from the Mediterranean, non-governmental organizations were forced to play an even more significant role in aiding refugees despite the struggle they faced in safely carrying them to shore. Frontiers were often closed and ships full of refugees abandoned, causing more migrants to die at sea. Today, nearly twice as many migrants have died at sea in 2021 compared to 2017, rising from 1 in 42 deaths to 1 in 22. This marks an exorbitant increase, considering that the number of arrivals during this time shrunk from 119,370 to 19,060 people.

The disproportionate impact of the crisis on Mediterranean countries spurred drastic anti-migration policies in 2018, beginning with the Italian government’s “closed ports” approach that blocked NGO ships carrying migrants from docking at their ports. This was largely a response to the EU’s system for verifying asylum claims, known as the Dublin system, which makes nations responsible for the procedures regarding migrant arrivals. Increasingly bearing the brunt of the migrant crisis, coastal countries began to find ways to prevent arrivals on their territory. While Italy recently overturned its “closed port” policy, the EU is still far from providing a sustainable system for sharing responsibilities amongst countries to support migrant arrivals. In a vicious cycle, a nationalistic approach to immigration has led far-right parties to gain traction in nearly every European nation, solidifying a widespread belief that migrants threaten European unity. Such thinking only reinforces the far-right’s rhetoric, despite the true crisis at hand being a humanitarian one, revolving around the increasing number of migrants facing deadly or inhumane conditions, both at sea or within the repressive regimes from which they attempt to escape. The lack of solidarity with coastal countries shown by other EU member states has fueled Italy’s exteriorization of border management, as exemplified by their agreement with the LCG.

By helping the LCG capture departing boats and ignoring the appalling conditions in Libyan detention camps, EU members are exacerbating the inhumane conditions experienced by migrants. By June 2021, 13,000 people had been forcibly returned to Libya, exceeding the total brought back in all of 2020. Considering that the International Organization for Migration (IOM) reports higher numbers of asylum-seekers attempting the passage this year, the final tally will likely be much higher. Nonetheless, many migrants continue to cross despite the blatant dangers awaiting them because any alternative seems better than being stuck in Libya, where horrific human rights violations are experienced daily by those in detention camps. Detainees face constant torture, from sexual violence to forced labour, and remain trapped unless they escape or pay exorbitant ransoms for their freedom. One survivor’s account detailed conditions in the Zintan detention centre, where approximately 700 migrants were held in overflowing and filthy living quarters; prisoners had no access to clean water and faced frequent malnutrition as food was withheld as a form of punishment.

European governments and even NGOs within Libya (often backed by the same EU funds that finance the LCG) have failed to adequately address the humanitarian crisis at hand, likely because of their role in engendering it. Many asylum-seekers, and even certain aid workers, have stated that there is little to no substantial assistance from the international community. They remain in the same conditions and continuously feel alone in dealing with the abuse they face, further highlighting how rare the prospect of support from European nations is today. Fear that the consequences of the 2015 migrant influx will recur, again spreading certain nations’ resources thin, is cited for the rise in support for anti-immigration policies.

However, the migrant issue remains rooted in the EU’s system for receiving asylum-seekers, which has a major shortcoming in its uneven division of responsibility among all union members. Should “better migration management practices [and] better migration governance” tactics be adopted, as stated by the IOM, accommodating the number of arrivals to Europe each year would be a feasible task. By spreading the demands for refugee support, both financial and other, among all member nations, the integration of migrants could become both smoother and more beneficial to refugees and states alike. The human cost of this refugee crisis has long come second to other factors motivating the EU’s decisions, a trend which desperately needs to change to reverse the recent trends of rising migrant deaths.

The challenges faced by North African migrants looking for a better life in Europe, from the dangerous sea crossings they attempt to the cruel treatment they face if returned to Libya, are unfortunately largely due to the EU’s continuous contributions to repressive regimes and actors. The role played by European nations in this crisis is far from the first and will likely not be the last. In Turkey, the EU has long been providing billions of euros in funds in exchange for the Turkish government to block the migratory route coming from Turkey towards western European nations. Considering the influence and resources of the European continent, it is lamentable that they choose to utilize their capacities to further the humanitarian crises seen in war-torn and transit countries instead of addressing the systemic violations of human rights seen abroad. Instead, developed nations continue to benefit from the suffering of the less fortunate despite a legal obligation to uphold international law. Their eagerness to find loopholes in longstanding agreements shows that the moral side of their duty is dangerously ignored, with decisions being made at the expense of the vulnerable populations they are supposed to be protecting.

Featured image “Refugees on a boat crossing the Mediterranean sea” by Mstyslav Chernov is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Edited by Grace Parish.