Kenya v. Somalia: Is the ICJ’s Legitimacy Collateral Damage in its Own Ruling?

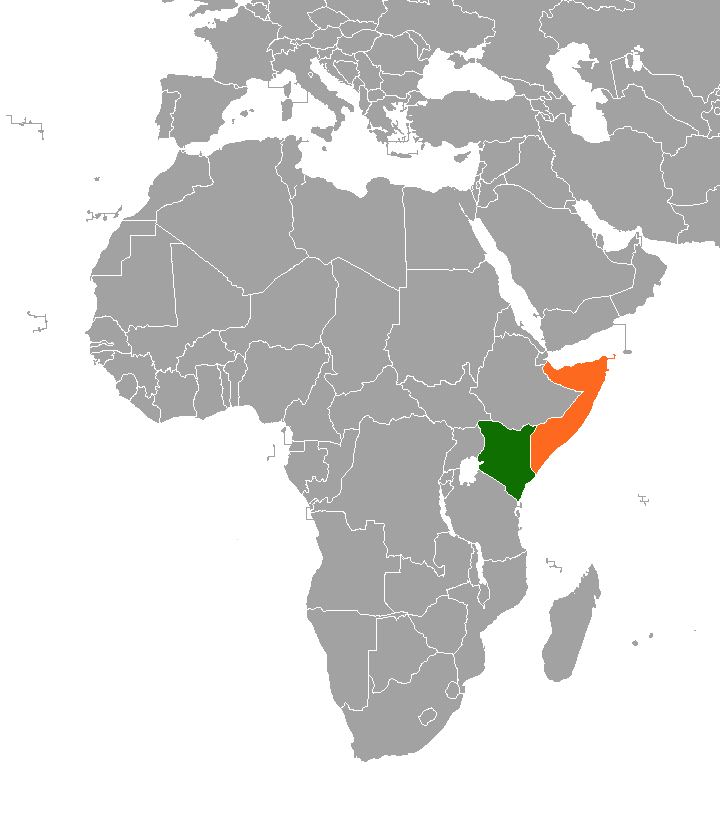

Flexing its muscles on October 12, 2021, the United Nations (UN)’s judicial organ, the International Court of Justice (ICJ), ruled in favour of Somalia over Kenya in a long-running maritime border dispute spanning over 100,000 square kilometres of the Indian Ocean. Following this ruling, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta made a public statement asserting that the country “rejects in totality” the ICJ’s decision. Assuming Kenya refuses to comply with the ruling, the state’s blatant disregard for the Court’s legally binding decision further contributes to the growing uncertainty surrounding the effectiveness of its power.

The ICJ, established in 1945, has the role of “settl[ing] legal disputes submitted to it by States and to give advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by authorized United Nations organs and specialized agencies.” In this case, the legal dispute was brought to the Court by Somalia in 2014 after out-of-court negotiations between the two states deteriorated. However, it was not until 2017 that the Court ruled it held jurisdiction over the case, citing both countries’ signatures of the Statute of the Court in 1963 and 1965. This gave signing states the right to bring any one or more states that have accepted the same obligation before the Court. Still, it took four more years for the ICJ to begin hearings on the case, before which Kenya withdrew from the proceedings after the Court denied yet another postponement.

As the disputed maritime area contains considerable deposits of valuable resources like oil, gas, and fish, both states hold a vested economic interest in a favourable Court ruling. Somalia argued for the demarcation of its sea territory by a line that runs southeast of its land border. In addition, Somalia sought financial reparations from Kenya, claiming violations of sovereignty. Kenya maintains that such demands are an “illegal grab at the resources of Kenya,” declaring that the boundary should follow the latitudinal line of its border. Applying the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which both states are signatories to, the ICJ judges unanimously ruled in October that there was “no agreed maritime boundary” in force between the two neighbours. Instead, it drew a new maritime border, allocating the majority of the 100,000 square kilometres to Somalia and affording Somalia exclusive fishing rights in the area. Nevertheless, the Court rejected Somalia’s demand for reparation payments, finding a lack of conclusive evidence that Kenya’s maritime activities had violated its sovereignty.

The Court’s ruling will undoubtedly further deteriorate the rocky Kenyan-Somali relationship. This strained relationship regarding borders dates back to 1963 when Somalia claimed part of Kenya’s Northern Frontier District, only to be later intensified by refugee migration to Kenya following the fall of Somalia’s dictator Siad Barre in 1991 and the institutionalization of the Islamic militant group Al-Shabaab in 2006. Since then, Somalia has accused Kenya of intervening in its internal political affairs, leading the country to cut off diplomatic relations in 2020. Since then, animosity between the two nations has only grown, with Somalia supporting Djibouti over Kenya for the United Nations Security Council’s (UNSC) non-permanent member seat. Kenya retaliated by hindering the issuing of visas on arrival to Somalis. This inter-state tension holds the potential to reverberate across borders, causing further regional instability within the Horn of Africa.

Moving forward, the ruling could pose profound economic and security implications for both countries. According to Meron Elias, a Horn of Africa researcher with the International Crisis Group, Kenya has been a major contributor of troops to the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM). AMISOM seeks to mediate the Al-Shabaab who regularly carry out attacks, utilizing violence to impose taxes and demand payments from civilians and businesses. Consequently, a Somali win at the expense of Kenya runs the risk of losing out of vital contributions of troops. Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta described the situation as a “zero-sum game,” stating, “this decision…will also reverse the social, political and economic gains and potentially aggravate the peace and security situation in the fragile Horn of Africa region.” Continuing his claims, President Kenyatta asserted that European countries with vested interests in the oil and gas industries were driving the ruling — Somalia previously held an auction for blocks of oil and gas in the disputed region in 2019.

In contrast, Somalia’s President Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed praised the Court’s ruling declaring that “justice has prevailed.” As the maritime dispute sparked nationalist sentiments, the ruling offers President Mohamed a political boost as he seeks a second term in office this election period. While the situation remains tense, it is unlikely to escalate into conflict due to a “weak federal government and a nascent maritime authority,” according to Timothy Walker, the maritime project leader at the Institute for Security Studies in South Africa.

Not only will the ICJ ruling have inter-state implications, but it will affect domestic interest groups as well. The contested area of the Indian Ocean is a source of income, and thereby livelihood, for fishermen. Fishermen in Lamu Country along Kenya’s northern coast will be especially impacted; according to think tank Africa2100, approximately seventy per cent of Lamu’s fishing derives from the contested triangle. As a result, the new exclusive fishing rights will severely limit Kenyan fisherman’s access, negatively impacting the communities livelihood. At least two fishing landing sites exist within the disputed area. Kenyan fishermen at these landing sites have already begun protesting, demanding “fair and impartial judgement” while calling upon regional bodies to intervene.

Although ICJ rulings are legally binding, they are entirely unenforceable, and many other countries besides Kenya have also chosen to ignore them. In the 1986 Nicaragua Case brought against the United States regarding its military and paramilitary activities in and against the country, the ICJ ruled in favour of Nicaragua. The Court demanded the US pay reparations for injuries and the removal of troops. Ultimately, the US refused to comply with the Court’s ruling. Nicaragua then brought the case to the UNSC to enforce the decision under Article 94 of the Charter. Yet, all attempts were vetoed by the US, exhibiting the ability of superpowers to manipulate the framework of these international organizations from their original purpose to necessitate favourable outcomes. More recently, the Court ruled in a case brought to it by the Philippines that China lacked a legal basis for its expansive claim to sovereignty in the South China Sea. Ignoring the ruling entirely, China refused to participate in the tribunal’s proceedings and reiterated that it would not abide by it. The ICJ’s long history of UN member states blatantly disregarding its legal rulings destabilizes the organ’s legitimacy within the international system. Adding to this dysfunction, when relevant parties refuse to comply with a judgement, the other parties can only seek recourse from the UNSC. But, within the UNSC, five powerful countries — the US, China, France, United Kingdom, and Russia — hold veto power and can then block action that could negatively impact them or their allies. As a result, situations similar to the Kenyan-Somali case highlight the much broader question of the effectiveness of international organizations within an anarchic system.

Featured image: “The United Nations Security Council Chamber” by Michelle Lee is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Edited by Grace Parish