Handheld Imperialism: American Tobacco in China

The cigarette is a ubiquitous institution. The streets of every major city are littered with their remnants, and the smell of tobacco smoke is nearly inescapable. Cigarettes are different things to different people — to some, they are vices to be removed from society; to others, they are social and cosmopolitan. To many young Chinese men at the turn of the 20th century, the cigarette was a sign of modernity that was sought with fervent desire.

After the American Civil War, American tobacco companies began to produce cigarettes with Virginia Brightleaf Tobacco in an effort to compete with the Turkish companies that wrapped Egyptian tobacco. These American cigarettes were brought to China between 1905 and 1937 by young men who marketed them as a signifier of Western modernity in the “desperately backward” East. Young men from tobacco-growing states in the American South travelled to China to exemplify their vision of the 20th century with the ‘cool’ American cigarette in hand. This marketing of the desired modern identity began in earnest in 1905, when American Bright Leaf Producers joined up with British Tobacconists and formed the British-American Tobacco Company, hereafter referred to as the BAT. This company represented a sort of ‘multinational imperialism’ under the guise of tobacco exportation. Britain and America targeted China for this joint colonial project to get China hooked on cigarettes in much the same way that Britain had once pushed opium in the vast and unclaimed ‘orient.’

Today, China is both the largest producer and consumer of tobacco in the world. There are more than 300 million smokers in the country, constituting approximately one-third of the total cigarette smokers in the world. 26.6 per cent of China’s adults smoke cigarettes, and 3,000 people die every day of tobacco-related illness. These deaths and the massive presence of cigarettes in China are direct consequences of the BAT’s aggressive marketing techniques. This marketing campaign tapped into the larger Chinese project of modernization and national development that was occurring at the end of the Qing Dynasty and into the years of the Republic.

The 1911 fall of the Qing Dynasty brought a crisis of national identity: what did it mean, in a modernizing and globalizing world, to be Chinese? Could Chinese men overcome the feelings of emasculation created by centuries of Western imperialism? How could China cease to be exploited by Western powers? How could China stop being the ‘sick man of Asia’ and become a respected member of the global economy? For some, the answer was to construct a vision of modernity that aligned with the industrial realities of their historical exploiters: Western powers like the US and Britain, both of which peddled a modernity marked by consumption and youthful liberation. BAT brands like Ruby Queens saw this crisis of modernity and masculinity unfolding and offered the cigarette as a cure.

The young men exported from the American South to China by the BAT portrayed themselves as cool, modern, and virile. They sold the cigarette as something that would give young Chinese men those same characteristics; a hand-held ticket to the modern world cloaked in the ardently admired “aura of jazz” (Enstad, 186). Jazz was seen internationally as something sophisticated, youthful, vibrant, sexual, modern, and distinctly American, so BAT subsidiaries sponsored radio programs and sent out men who played jazz and smoked bright leaf tobacco. Capitalist interests constructed modernity out of the haze of cigarette smoke. In doing so, they took Jazz from Black communities in the segregated south and turned it into a tool of economic manipulation, the effects of which are still very present in China.

In the early years of the Republic, around 1915, cigarettes exploded in popularity and the BAT once more leveraged the tenuous national identity in China for profit. Bright leaf tobacco fetched a high price but was expensive to grow. Chinese farmers were drawn to the possible profits of Bright Leaf, despite the fact that they didn’t have the necessary equipment to cultivate it. In an impressive show of manipulative benevolence, the BAT began to loan coal, fertilizer, and machinery to Chinese farmers. For the privilege of using the equipment and participating in corporate modernity, the BAT charged these farmers interest and thus, with a rueful smile, the BAT created a labour force completely dependent on themselves and their equipment. This labour was both indebted to the company and cheaper than the labour force in the American south, and so the BAT made use of the political and social influence won in China by “a half-century of imperial wars and arm-twisting diplomacy” to exploit a group anxious for inclusion in the global world.

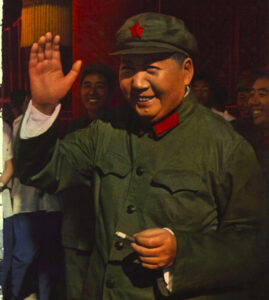

Mao Zedong’s anti-Imperialist policies stamped out many signifiers of Western exploitation, but the cigarette remained strong. Ironically, Mao championed self-sufficiency and anti-imperialism with a cigarette in hand, albeit one produced by a state-owned factory. He even went so far as to promise “food, shelter and cigarettes” to his troops during the civil war. Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese leader who led the post-Mao reforms and oversaw the rapid capitalist expansion in China, was well known as a chain smoker. Deng Xiaoping and his pack of Panda cigarettes helmed China’s second modernization and reified the intimacy between China, cigarettes, and inclusion in the Western world. These intimate linkages are a testament to the realities of the legacies of imperialism in a corporate age; they are legacies that often exist unconsidered and unchallenged. Cigarettes are a given reality in most countries. In China, they are also a visual signifier of the aggressive expansion of corporate America, and the thousands of daily tobacco-related deaths testify to the devastating effects of the pursuit of profit by any means.

Featured Image: Brightleaf Tobacco Warehouse, Virginia. VCU Libraries, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Edited by Devanshi Bhangle