War and the World Wide Web: The Rise of The Splinternet

On February 24, 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a “special military operation” and began a months-long invasion of Ukraine. Just days later, North American and Western European countries placed a series of economic sanctions on Russia. The country is now economically disconnected from the Western world, with only a few paths remaining open as many countries rely heavily on Russian energy exports. In addition to announcing their support for Ukraine, many private companies have also taken matters into their own hands, either withdrawing entirely or ceasing all ongoing operations within Russia. These actions put the structural integrity of the internet at risk, as countries may decide to move cyberspace operations within their own borders, leading to the development of a separated digital infrastructure and the possible fragmentation of the internet.

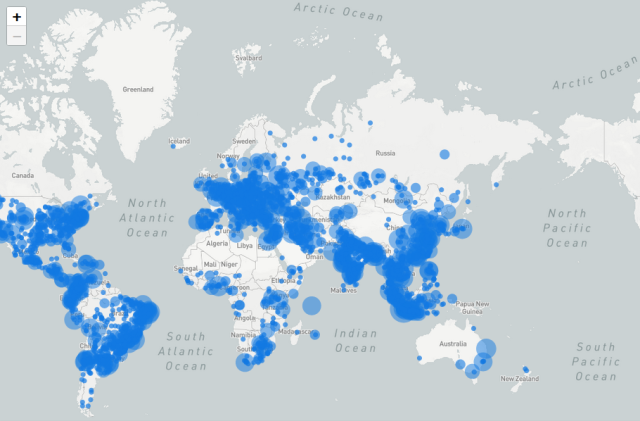

Both physical and digital companies have sanctioned Russia. Name brands such as McDonald’s and Starbucks are ceasing operations throughout Russia. However, lesser-known companies, who are also taking a stance, have a more immediate detrimental effect on the digital lives of Russian citizens. Physical infrastructure companies like Cogent and Lumen, which provide a backbone to the internet via hardwired infrastructure throughout Russia by connecting it to the rest of the world, are pulling out, vastly limiting the number of websites that Russian citizens have access to. Likewise, Silicon Valley-based tech giants are making efforts to slow their operations in Russia, while also trying to strike a balance with limiting Kremlin disinformation and propaganda. However, the exodus of tech giants from Russia is not a one-way street. The Russian government has blocked social media applications like Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, even going so far as to declare Facebook and Instagram’s parent company Meta an “extremist organization.”

The scale of these targeted sanctions and withdrawal of internet-based companies from one specific nation is major. Actions taken by countries and the private sector around the world have effectively created a digital wall around Russia, compromising the structure of the internet, as it has been shown that a country can be temporarily blocked at a moment’s notice. This further calls into question the role of private tech companies in facilitating internet freedom in authoritarian countries despite still supporting their economy through their services. Historically, private tech companies have cooperated with authoritarian countries in order to continue to conduct business, but with stakes so large, they have taken matters back into their own hands by supporting the facilitation of free speech in times of trouble and in areas where it would have otherwise been difficult to access such a thing.

The tech industry is facing a dilemma it has faced for a while: striking a balance between connecting all parts of the world and risking the spread of disinformation. In Ukraine, videos posted on TikTok and Facebook have shown the horrible truth and catastrophes that take place on the battlefield to the world in face of the Kremlin’s repeated lies. Similarly, before being blocked, Russians were able to use these same platforms to seek truth about a situation that they were otherwise being fed propaganda about by Russian state media. Social media, despite its many controversies, is a highly valuable tool that allows for uncensored discourse without the fear that someone is unknowingly listening in.

Prior to the war, Russia was in a unique position where, given its somewhat authoritarian characteristics, it was still connected to the entirety of the internet. Users could access alternative sources of information if they wanted to. Unlike China and Iran, where the government has tight control over the internet and regularly censors foreign websites and dissent. The actions and sanctions taken against Russia have had the same effect, giving Russian users no other option but the government-approved companies and services permitted to operate in its country.

Even though they have been almost entirely cut off from Western infrastructure previously connecting them to the internet, some hardwire connections still exist to Russia’s East, allowing data to pass through. In an effort to decrease its reliance on foreign infrastructure, Russia has intermittently created its own in-house Domain Name System (DNS), a tool that directs web browsers to their requested website. If Russia chose to use their own DNS, the government would be in a position to completely control what is allowed on its own state-approved internet. This pairs perfectly with a law that forced Russian internet providers to install equipment to monitor internet traffic and increasingly centralized control of Russia’s communication networks. Similar lesser-known laws have Russia headed towards a path of completely controlling the flow of information in and out of its borders. They have not cut themselves off from the global internet yet, but there is no telling what may happen in the future.

Furthermore, near the beginning of the war, Ukraine asked The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN), which oversees the worldwide DNS, to revoke .ru addresses. This plays right into Russia’s fear of being cut off from the internet. If things escalate enough, actions like these can be the incentive needed to take matters into their own hands to isolate themselves from foreign sites when the time is right. In line with their beliefs, ICANN denied Ukraine’s request saying they were “built to ensure the Internet works, not for its coordination role to be used to stop it from working.” Correspondingly, VPNs have played a vital role in ensuring Russian citizens’ access to impartial news sources. At the height of the conflict, installations skyrocketed, allowing users to bypass restrictions imposed by Russia itself and other parties cooperating with the sanctions in place. As much service as they can provide in bypassing digital restrictions and censorship, VPNs are not a complete solution in the face of government restrictions on internet freedom.

With all that is happening in Russia, it is unknown if they will even seek to rejoin the rest of the internet when the conflict ends. They have shown that they can function as a statewide internet if they want to, furthering the “balkanization” of the Internet. Put simply, “the vision of a free and open internet that runs all over the world doesn’t really exist anymore.” Russia is not the only country where worrying activities are taking place. China has exhibited great success in controlling information with its “Great Firewall.” On a smaller scale, the European Union has taken similar steps in the name of data privacy and protection – but in the wrong hands, these measures can be detrimental. Innocent users are slowly running out of options for an internet that respects them and is not tied to some form of state surveillance measure. Actions must be taken to preserve what we have now, if not improve on it: to create a more user-centric and democratic internet that was the vision of the first implementation of the World Wide Web.

Featured Image: Locked Internet by piqsels licensed under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License

Edited by Adam Steiner.