Israelis are Back to the Polls Again, for the Fifth Time in Three Years

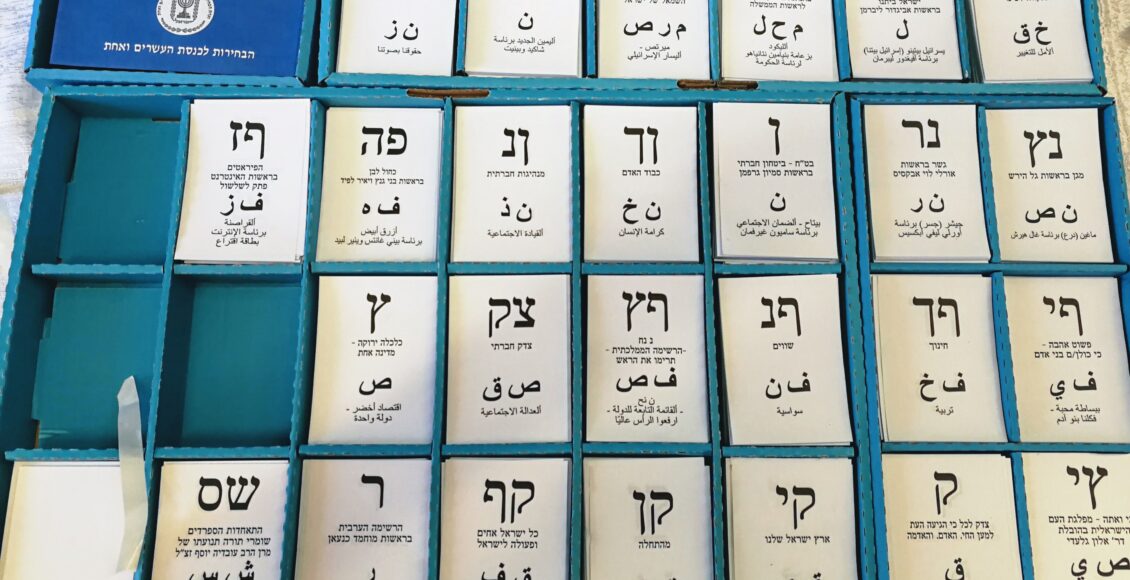

Ballots of the Israeli 2019 legislative election (Laliv Gal/ Wikipedia)

Ballots of the Israeli 2019 legislative election (Laliv Gal/ Wikipedia)

The large but fragile coalition led by Naftali Bennett collapsed in June after only a year in government. Though Israelis are tired of this era of governmental instability, the current political conjuncture seems to be here to last. Israel has a parliamentary system in which the Prime Minister and Members of Parliament (MPs) predominate. MPs have repeatedly voted in defiance against the government over the last few years. If the government does not get the support of the majority, the President dissolves Parliament and calls voters to the polls.

Israel’s ongoing governmental instability rests on various factors well-entrenched in the country’s politics. The governmental crisis is entrenched in the Israeli parliamentary system’s rules because election winners struggle to form governments. Moreover, Israel’s rising political fractionalization contributes to parties’ reluctance to build alliances and fosters governments’ collapse. Finally, the lack of political renewal, which boosts voter fatigue and threatens Israeli democracy, is crucial when explaining why Israelis are returning to the polls on November 1.

Failures of the Israeli parliamentary system

Parliament – the Knesset in Israel – has been the source of many issues in recent years. The President charges the party with the most seats to form a government by building alliances with other parties. Nonetheless, the two rival coalitions sometimes tie, like in 2019 when they both collected 60 seats, preventing them from forming a government. Coalitions often end up with a similar number of seats, and no clear winner emerges. For instance, in 2020, both coalitions failed to gain the majority of the seats – 61 seats – because the right-wing coalition won 59 seats and the center-right bloc captured 52 seats. Consequently, coalition governments are relatively weak and unstable because an alliance can collapse if a couple of MPs decide to leave it over political disagreements. That is what happened to Bennett’s coalition this June when two MPs successively left the alliance.

This trend of governmental instability has been on the rise for 20 years in Israel. This year’s election is the tenth since 2003. In comparison, there have been only 15 elections between 1948 –Israel’s creation – and 2003. Therefore, recent electoral results have exposed the Israeli parliamentary system’s limits and inability to build lasting governments.

Political fractionalization in Israel

Israel is undergoing an unparalleled wave of political fractionalization, which tremendously contributes to the country’s governmental instability. Fractionalization is now a key trait of Israeli politics because of the many contentious issues between parties. Diverse ethnic and religious groups, ideologies, and principles shape Israel. For example, there are tensions between secular and religious groups, pro-settlement and pro-Palestinian rights, and socioeconomic groups, among others. Coalitions are often unstable; while parties may be able to unite on some issues, they diverge on many others. For instance, Bennett’s government collapsed after a vote on a law supporting West Bank settlers in June.

Israel’s political fractionalization fuels the ongoing governmental crisis because parties struggle to find compromises to build alliances. For example, there is a powerful right-wing movement in Israel, but its strong internal divergences make it difficult to form coalitions. Yisrael Beiteinu is a nationalist secular party that provoked the collapse of Benjamin Netanyahu’s alliance in 2019 because it refused to govern with ultra-Orthodox parties despite their many shared political views. Yisrael Beiteinu’s opposition to Shas and United Torah Judaism over religious matters was a dealbreaker. Political fractionalization implies that even if parties share political beliefs – all nationalist parties in that case – one disagreement over a critical issue can break apart a potential coalition. This episode fostered the current political crisis because it led the President to dissolve Parliament and launch a new election. Therefore, Israel’s parliamentary system gives substantial power to minor parties in coalition building because they represent the key seats a major party needs support from to access power. Yisrael Beiteinu had only five out of 120 seats in the 2019 Knesset but caused Netanyahu’s failure to secure power.

The last government tried to overcome political fractionalization and was a large coalition of parties across the political spectrum. Hardline conservative Naftali Bennett-led alliance included some left-wing parties, right-wing parties, nationalist parties, and even an Arab party for the first time in Israeli history. A broad range of issues animated this coalition of secular parties, religious groups, several pro-settlement parties, and a pro-Palestinian leader. Though the common desire to oust Netanyahu from power – he ruled for 15 of the last 25 years – united the coalition, its significant ideological divergences led to its downfall.

The lack of political renewal

The absence of new sweeping political figures in Israel strengthens the ongoing governmental instability. Moreover, the right has dominated Israeli politics for over two decades. Israel shifted to the right after the 1993 Oslo Accords’ failure. The collapse of the peace treaty between Israel and Palestine exacerbated tension between the two camps, leading to the Palestinian second intifada in the early 2000s and the rise of Hamas in Gaza. Those events raised security concerns in Israel and stimulated the right. The demographic conjecture also helped right-wing parties to prosper because of the significant demographic growth of the religious population, which has historically voted for right-wing parties. The shift to the right has electoral consequences. For instance, right-wing parties won more than two-thirds of the seats in the 2021 election. Netanyahu managed to surf over the minor differences between right-wing and nationalist parties to secure power for 15 years and become the longest-serving Prime Minister in Israeli history.

Various new leaders emerged in the last two decades but failed to generate lasting influence. Benny Gantz was the frontrunner against Netanyahu’s Likud Party in 2019, but he gradually lost importance. Gantz shared similar views with Netanyahu and even governed with him in 2020 after claiming he would never do so. Nevertheless, voters will always prefer the original over the copy, which is why Netanyahu still dominates among right-wing leaders. Furthermore, Bennett’s government might foster Netanyahu’s comeback to power because this political alternative has proven to be a failure. Voters might vote for Netanyahu again since they know his capacity to govern.

Israel’s lack of ideological and leadership rotation makes voters less attracted by the democratic process but also politics in general. The multiplication of elections boosts “voter fatigue” because citizens are less excited about politics since every election has the same outcome: Netanyahu in power or the impossibility of forming a government. Voters have less trust in the democratic system because the same figures have been in power for almost two decades, and Bennett’s government – the first rotational one for a long time – failed. Therefore, the current governmental crisis may be a threat to Israeli democracy.

Israel’s fifth election in three years is a landmark in the country’s political history. The two most likely outcomes seem to rest on Netanyahu’s fate. The former Prime Minister may regain power and continue his push towards more right-wing, religious, and neoliberal policies at the expense of political change and the ideological foundations of Israel. On the other hand, Netanyahu could fail to capture enough seats, and the country would go deeper into governmental instability and the political crisis it creates.

Featured image by Laliv Gal is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Edited by Max Rosen