Aid and Politics: The Weaponization of Humanitarian Assistance

Aid failure in Northwest Syria

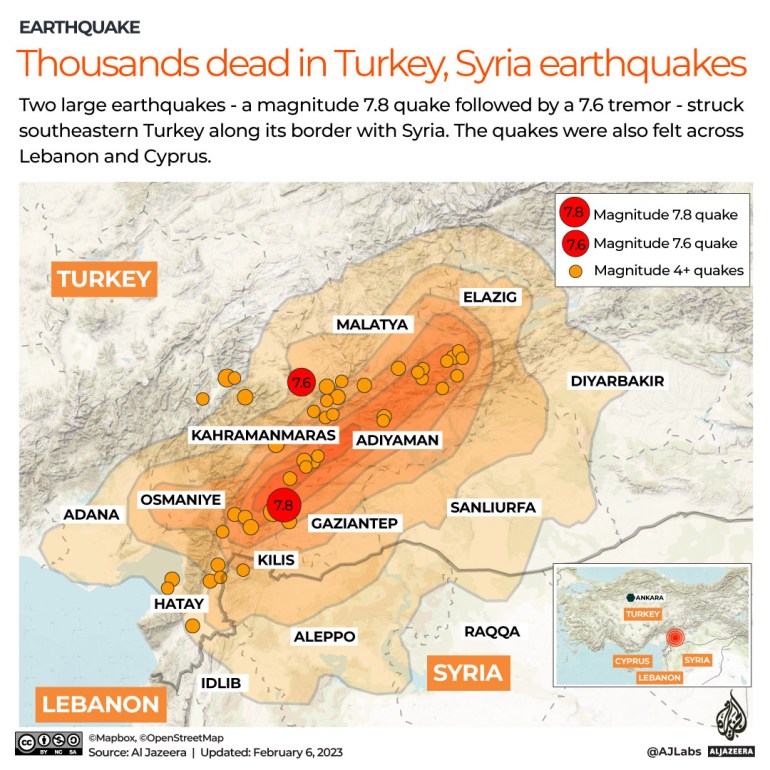

On February 6, a 7.8 magnitude earthquake hit Northern and Western Syria and South Central Turkey. The disaster has claimed an estimated 50,000 lives and caused tremendous damage to a region struggling with over a decade-long civil war and refugee crisis. The extent of the catastrophe caught the international community’s attention, with various countries pledging to deliver aid to the affected areas. However, as international assistance started pouring into Turkey, efforts to support northwestern Syria failed, leaving thousands of residents feeling abandoned by the international community.

Map illustrating the earthquake’s impact on Turkey and Syria on February 6, 2023. “Thousands dead in Turkey, Syria earthquakes,” by Al Jazeera, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

This is not the first time Syria has been in the global spotlight, and certainly not the first time it has been neglected by foreign aid. Entrenched in a civil war since 2011, its population has suffered the consequences of a collapsing economy and a humanitarian crisis. Unfortunately, the diplomatic sanctions and territorial division that followed have made delivering aid difficult.

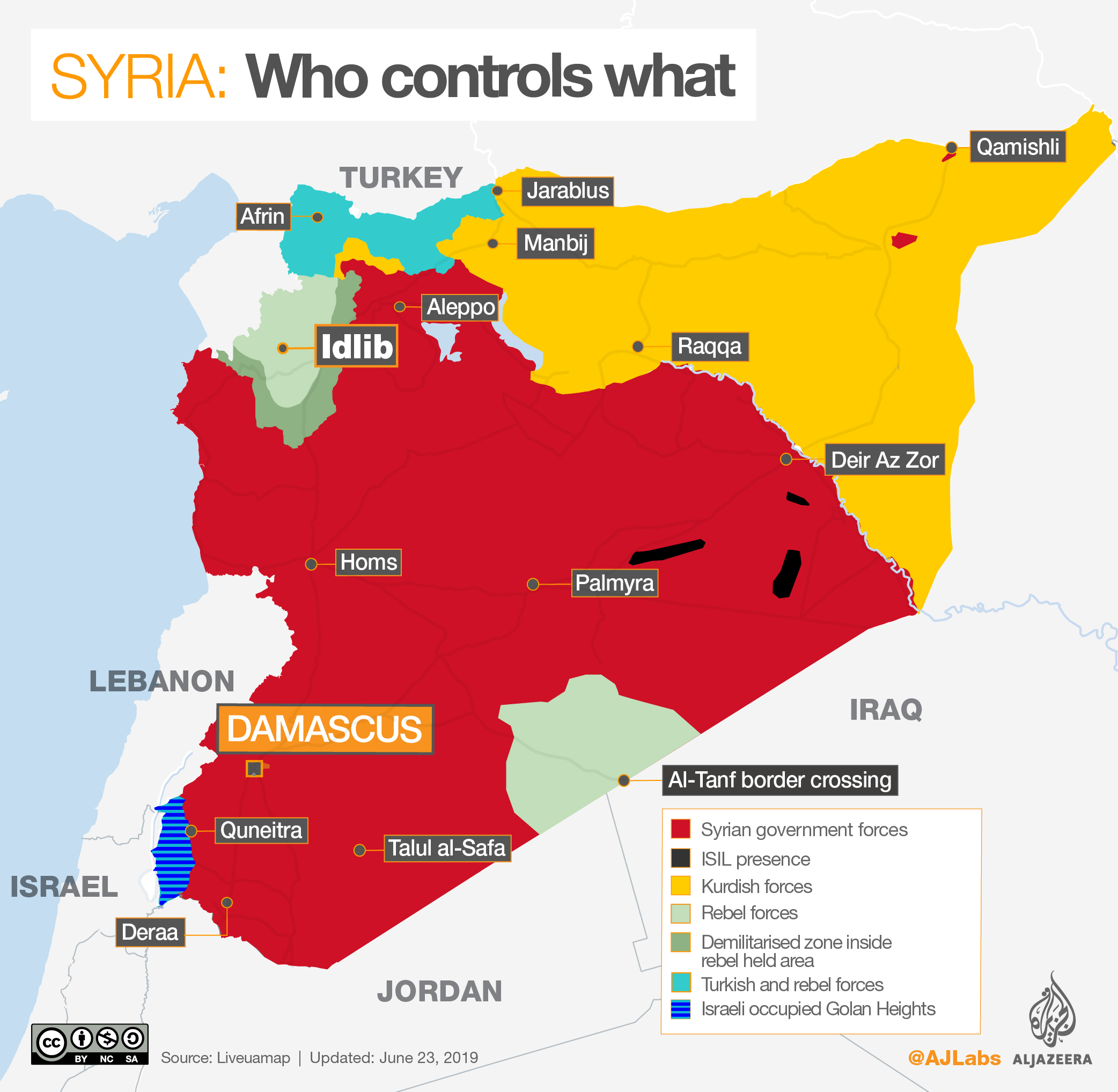

Over the years, aid has been delivered to the northwest part of the country through the Bab al-Hawa land crossing with Turkey, allowing Syrians to meet their basic needs and survive. However, when the earthquake hit, this land crossing was damaged and remains closed–thus impeding much-needed aid delivery. Despite the seriousness of the situation, the international community has been slow to respond efficiently. The latter has failed to prevent politics and corruption from hindering aid efforts and to facilitate delivery measures, compromising the lives of thousands of Syrians. Aid only enters the region once the UN Security Council has approved it. This is problematic since, over the years, Russia and China have vetoed UN efforts to open additional humanitarian crossings. They claim that this move would undermine Syria’s sovereignty, reducing its chances of gaining back control over the rebel-controlled areas in the North. Russia’s acts to deter relief delivery to the Syrian people sheds light on its larger involvement in the Syrian civil war as it has backed Bashar al-Assad’s regime. In 2015, Russia decided to give full diplomatic, political, and military support to Assad’s regime, against which the opposition forces were progressively acquiring more territory and getting closer to Damascus. Russia’s military intervention brought little change to the war’s outcome. However, it successfully prevented the collapse of Assad’s regime, helping him recapture the territory he had lost to the rebels. Thus, Russia’s behaviour in the Security Council can be seen as an effort to assert the regime’s sovereignty by preventing opposition forces from exercising any efficient authority (such as administering and managing aid) that would reinforce their control over the seized regions. Consequently, millions of Syrians are deprived of lifesaving aid.

Within the first few days following the earthquake, Assad’s regime insisted that all aid delivered to Syria should exclusively come through Damascus, as the central government would administer its distribution and delivery. However, it is hard to believe that the government would have shared this aid efficiently and provided it to rebel-controlled areas. In 2019, Human Rights Watch released a report accusing the regime of developing a “policy and legal framework” allowing the diversion of humanitarian aid to punish opponents and benefit loyalists.

On February 13, Assad authorized the UN to deliver aid to rebel-held northwest areas through two additional crossings for three months. Nevertheless, whether these relief efforts will be efficiently managed and distributed to benefit civilians rather than satisfy alternate political motives remains to be seen.

Another obstacle to aid provision in Syria is that European countries and the United States still sanction Assad’s regime and have expressed their reluctance to engage in formal relations with his government and directly send it aid. However, alternatives do exist. Ned Price, the US States Department spokesperson, said that the US was committed to delivering aid to Syria, but only through NGOs, as directly engaging with a government that has “brutalized its people over a dozen years” would be ironic and counterproductive.

Notwithstanding, after initial resistance, the US agreed to ease some of its sanctions on Syria to facilitate aid delivery. This, however, still shows how political considerations can mark decisions regarding humanitarian aid and delay its delivery.

The weaponization of humanitarian aid

Foreign aid is, in theory, provided to countries gripped by poverty, conflict and war with the expectation that the central government will efficiently use it to improve people’s lives and stimulate economic and human development. Yet, in practice, we see that aid falls short of its purpose as countries, due to political interests, fail to provide it to countries in need, or the receiving central government fails to administer it efficiently, co-opting aid for its own purposes. Since there is no effective international system controlling states’ use of humanitarian aid and holding them accountable for their misuse, political actors have been able to abuse assistance and use it as a strategic tool to satisfy their interests.

It has often been the case that states have deprived their population of humanitarian assistance to pressure opposition forces to surrender. This was the case in Syria in 2011. Following the outbreak of a revolution, the regime denied aid to large segments of the society for civilians to pressure rebel groups into surrendering. Instead of using the provided aid to ensure the survival and well-being of their population, aid is weaponized. As such, ensuring the state’s survival and defending its sovereignty is once again prioritized over improving human rights and people’s life. Having states holding so much power regarding the delivery of aid is problematic since aid can be used to acquire concessions from external and domestic actors. In the case of Syria, Assad could use aid as leverage against rebel-controlled areas.

Map illustrating which actor controls which areas in Syria; the northwestern region is under rebel forces. “Syria: Who controls what” by Al Jazeera, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

The state hopes to contain the opposition and assert its power by weakening the civilian population. The Ethiopian government also used this tactic in the war in Tigray. It imposed a two-year blockade in the Tigray region hosting rebel groups to prevent the delivery of aid and services to millions of civilians. Starvation is being used by the Ethiopian government as a war weapon against Tigrayans, endangering the livelihoods of millions of people. Such acts attest to the repressive nature of the Ethiopian state as it does not act according to its fundamental purpose to protect its civilians but instead is willing to deprive its citizens of their rights and security to ensure its survival. States should not be able to unilaterally decide which segments of their civilian population will receive or not foreign assistance.

Providing aid in an international system characterized by power competition is challenging. As seen in the case of Syria, political interests and sovereignty concerns have taken precedence over safeguarding human rights. Thus, states seem willing to hinder aid efforts to ensure their security and power. It is paradoxical to think that states are the primary guarantors of their citizens’ human rights and safety when they are often the root cause of their suffering. Power politics should not impede the management and resolution of humanitarian crises.

Individuals should and must remain the priority. International mechanisms should be put in force to hold states accountable for their misuse of aid and prevent any permanent member of the Security Council from vetoing relief efforts. As the Syrian case shows, since 2011, political interests and corruption have hindered aid efforts, endangering the lives of millions of Syrians as they were left to deal with a crippling humanitarian crisis. The international community has failed to prevent the politicization of aid, and now is the time for a change.

Edited by Justine Peries

Feature image: “EU’s response to the earthquake in Türkiye and Syria” by EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.