Gender Discrimination in South Korea

A woman wearing a short, tight-fitting jeogori (jacket) and a plump chima (skirt) / A man in durumagi (traditional topcoat)

(Source: Han Style)

A woman wearing a short, tight-fitting jeogori (jacket) and a plump chima (skirt) / A man in durumagi (traditional topcoat)

(Source: Han Style)

Confucianism was, and still is, deeply rooted in South Korea’s society. One particular theme is patriarchy where each gender has its own role in a family. Family is an important functioning unit of society in South Korea; the society functions like a big family in which they identify their rankings by age. And each gender has its own social construct formed by the society’s expectations and traditional ideologies. Although the patriarchal culture has undergone changes as South Korea continues to develop in the modern world, the mentality of gender specific role seems to remain strong within the society, inherently bearing gender discrimination, particularly in justice, the entertainment industry, marriage life, and employment.

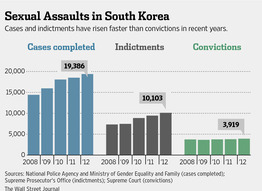

Graph retrieved from the Wall Street Journal

It turns out that males in South Korea receive a more lenient judgment in court than females for sexual crimes. Many rape or sexual assault charges were dropped simply because the prosecution, dominated by male, was often convinced that the convicted will not attempt the crime again and concerned for the impact of the criminal record on these men’s future employment (see graph on the left). One example was of a young woman raped by a drunk man. When she pressed charges against the man, police officers had tried to persuade her to drop the charges. Despite the effort of setting up a Ministry of Gender Equality and Family in 2011 and launching a special sex crime task force in 2013, many of the sex offenders are not being punished by the justice system. Chang Pil-wha, director of the Asian Center for Women’s Studies at Seoul’s Ewha Womans University, remarked that the issue is the deeply rooted mentality that sustains the patriarchal culture within the Korean society.

Furthermore, there is gender discrimination in job recruitment. Male are judged less hard in seeking employment compared to females in South Korea. Because of the Confucius ideology that women have the role of taking care of the family, employers are more reluctant about hiring a female, fearing that she is more likely to quit working certain stages of her life. Employers tend to believe that female employees are going to resign after getting married or bearing a child. Hence, employers discriminate against non-single female job seekers. In fact, many employers are accused of asking female job seekers about their plans after marriage and giving birth, which has led to the Ministry of Employment and Labor prohibiting employers to ask such questions to female jobseekers in the future. Nevertheless, by interviewing some South Koreans university students, female job seekers, typically newly graduates, face higher expectations when applying for jobs – such as higher grades. In addition, females are judged more by their physical appearance rather than their capabilities. In certain extreme cases, there are physical appearance requirements specifically for its female applicants: for example,“Wanted: women over 165 centimeters in height and under 50 kilograms in weight.” On the other hand, men are generally recruited to a more important position in the company, such as in management than sales. Overall, males have better prospects in securing employment.

As aforementioned, under the impression of the Confucius culture, South Koreans have assumed different roles for each gender. Women are expected to raise the children and take care of the household while the men work to be the main financial supporter of the family. Many women, therefore, chose to stay home, take care of the children, and resign if they had worked before marriage or giving birth. This mentality is still deeply rooted in the modern South Korean society as 22% of married women quit work because of childbirth and 41% resigned due to marriage. While more and more men respect their wives’ decision on quite working after giving birth, still many share the idea that females should stay home for childcare during the child’s early critical development period.

(Source: Han Style)

The entertainment industry also likes to exaggerate these different gender roles. Females and males typically convey certain characteristics and they are expected to behave in certain ways to be labeled as female or male. Although females often receive disadvantages from the society, males are often discriminated against in the entertainment industry by its portrayal of how a male is supposed to be. For example, males are expected to live by societal expectations such as serving the army and financially supporting the family, which are emphasized in films and television dramas. This compels the men to bear more responsibilities or to conduct their behaviour in certain ways. These stereotypes are projected to the public in South Korea and also reflect the social construct of different gender roles. Female and male celebrities are also judged with a different set of criterion – a double standard. Male celebrities enjoy the privileges of having the public accepting their wrongdoing easily; female celebrities often are subjected to more critical judgement from the public, particularly appearances.

In conclusion, although South Korea’s gender equality has been progressing, the traditional mentality of patriarchy is still deeply rooted in the public that affects many things from individuals’ personal lives to their work. Also, this gender discrimination is often explicitly or non-explicitly projected in entertainment industries. Changing the foundation of the Korean culture will be hard but as the society develops, hopefully women can be seen as equals to men in terms of ability. The rising awareness about feminism in South Korea can also be advantageous for men, as it may uplift some pressure of being the sole financial benefactor of a family.

References

- Highlights Korea: Babies and Bosses – Policies towards reconciling work and family life. (2007). Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/korea/39696376.pdf. from The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) http://www.oecd.org/korea/39696376.pdf

- Hyun-ju, O. (2015). Guidelines issued on sex discrimination in hiring. The Korea Herald.

- “Interview with Hong Seung Pyo”. Conducted by Rachel Chan. (2016).

- “Interview with Im Ju Won”. Conducted by Rachel Chan. (2015).

- “Interview with Lee Je Hoon”. Conducted by Rachel Chan. (2015).

- Jin-young, C. (2014). Government Policy Not Working – 22% of Married Korean Women Quit Their Jobs. Business Korea.

- Park, B. J. (2001). Patriarchy in Korean Society: Substance and Appearance of Power. Korea Journal, 41(4), 25. Retrieved from http://www.koreasociety.org/doc_view/353-patriarchy-in-korean-society-substance-and-appearance-of-power-by-boo-jin-park

- Strother, J. (2013). South Korea Struggles to Confront Stigma of Sexual Assaults. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304682504579154571193810410