Drop It Like It’s Hot – A Letter to Petrol Exporters

The sun is setting on our frivolous flirtation with cheap oil and free-flowing gasoline.

The sun is setting on our frivolous flirtation with cheap oil and free-flowing gasoline.

It’s sticky, dark, viscous, and carries such labels as “sweet” or a certain “blend.” No, not chocolate or coffee – oil. As the main ingredient in plastic bags to gasoline, oil is the base for everyday life. Accordingly, it is massively tapped and wildly volatile. In the past decade, oil has been on a rollercoaster, experiencing rapid fire price changes. This has recently come to a head in the previous two years – oil saw its price drop nearly $100 per barrel. Countries that are solely reliant on oil as their breadwinner have seen this situation bring about devastating consequences. To tame this calamity the heavyweights in question – Russia, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, and Qatar – are mulling over an agreement to freeze oil production to artificially rise prices back to “safer” levels. While the call to action may be deafeningly loud for these countries, this sort of response will do them no favors. It behooves this cabal to go back to the drawing board.

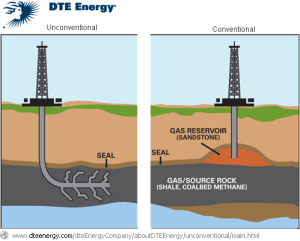

One may ask, with the culture of consumerism on the rise domestically and abroad, why is the price of oil dropping? The answer is rather simple: the United States. In the past half-century, oil has been primarily sourced from the Organization of Petrol Exporting Countries (OPEC) and their friends. America has had a tumultuous history with OPEC, so it did the obvious: it began focusing its energy on producing oil itself. Hence the newest trend in oil production: shale oil, a variant obtained by “fracking” deep sweet crude reserves in the earth. Shale oil now comprises a sizable chunk of American oil consumption, meaning an enormous disruption in traditional oil exchanges. The market for oil is now half as big, but the producers are now twice as many. This has led to a financial game of chicken, where each party drops prices lower than the other in hopes to provoke a greater response. Another good question would be, why is low oil such a bad thing? Oil is one of the earth’s most expansively traded commodities. Its flow and use in the financial system often indicates how healthy global securities, exchanges, and transactions are at the current moment. History has shown us from the 70s to the 80s that neither oil deficits or oil gluts are beneficial to the global economy. A golden middle ground should be pursued.

The problems with the four-way agreement to freeze oil production at current levels split into two parts: inefficiency and the Iranian conundrum. I will address these in that order.

The name of the game is balance. Oil prices are about keeping all worst-case scenarios at bay – relative to each other. A second-tier, but inadvertently most influential, factor shaping the state of affairs is the gigantic reserves of oil stored away in quantities that we have not seen since the 1980s. With such a bulbous growth on the supply side, as economist Liam Denning phrases it, “it is little wonder that this is not exactly a seller’s market for crude oil dated for delivery soon.” This should be considered in tandem with productive capacity, which around the world is in the high 90s (percentage-wise). An inherently overpriced good, such as any commodity (oil included) will sell for much cheaper if it is becomes clear what the size of the total global supply is, which was unclear when reserves were smaller and production rates were slower. The other worrying component is the turnaround time that it will require to effect serious change on the situation. By current estimates, the freeze will take 60 days for the turnaround to impact the market. 60 days in a market where oil, ISIS, and Russian sanctions bite at global affairs, which all impact oil prices, with hungry abandon is walking on a limb. The possibility of a wayward event shaking up the recalibration process is all too great to risk on a conflict-ravaged chessboard such as this. In the worst case scenario, we may see the supply for oil expand in complete discoordination with the constricting supply of oil in the world, setting the crisis deeper into our lives.

Iran is balance’s alacritous little cousin, always nudging her way into places she ought not to involve herself. Fresh from international time-out, Iran will be eager to enter the exclusive oil exporters’ club. The means: flooding the market with their own oil. Since the current oil demands are being met, excess bought oil will be stored into the reserves mentioned previously. They are already large enough to cause a substantial headache. If Iran begins using these reserves as a makeshift bank, the world’s oil supplies may go haywire. It is also important to remember that Iran’s reemergence as an oil power, and subsequent increase in net oil trade, will be welcomed by manufacturers, who are looking to get raw materials as cheaply as possible. Moreover, given the current ice-cold relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, it is quite possible an Iran-induced oil glut will elicit a knee-jerk reaction from Saudi Arabia to begin exporting oil at double the speed at which Iran will be exporting. This would mean a destructively dramatic increase in worldwide oil production that would renew the aforementioned game of chicken, only this time it will happen as a sudden breakout from unstable equilibrium and the two parties will be the two highest-potential oil exporters in the world. This pair, if they so desired, could potentially run the price of oil into the single-digit numbers (where oil becomes as bountiful as air or water),which would be a socio-political-economic disaster, purely owing to the tectonic shifts that would occur in the global economy, currently ruled by oil. The Iran factor is simply too great and unpredictable to leave unaccounted for in the calculus of the oil production freeze. Perhaps this factor could be mitigated by a formal agreement between Saudi Arabia and Iran, but the atmosphere between these two countries makes that proposition a pipe dream.

It would be nice to assume that the countries who created this mess in the oil market could contain it, if not clean it up. Oil drops of such proportions are never safe or sustainable, so while cheap road trips are nice, a peaceful world and stable interest rates are better. It would be better, perhaps, to approach the oil wars with a more strategic, levelheaded solution, incorporating the environmental, geopolitical, and financial interests of all those involved. Shale oil’s stake, just like OPEC’s, has become indelible from the crude oil exchange. What started as a momentary rejection of the status quo is now demanding a complete overhaul of the global energy chain.