A Girl In the River: Oscar-Winning Film to Create Change in Pakistan

Oscar by Craig Piersma from Flickr Creative Commons

Oscar by Craig Piersma from Flickr Creative Commons

On the night of the 88th Academy Awards, director Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy took home an Oscar for her film, A Girl In the River: The Price of Forgiveness in the best documentary short category. Portraying acid attacks on Pakistani women in her first Oscar-winning film, Saving Face, this time she tackles the subject of “honour” killings in Pakistan that affects 1000 women every year. Honour killing is defined as “killing of a female, and sometimes her love-interests and other associates, for supposed sexual or marital offenses, typically by her own relatives, with the justification being that the ‘offence’ has brought dishonour to the family.” For the rare few who do not die from these vicious attacks, they are pressured by the community elders to forgive their aggressors to retain peace and order and absolve them of any guilt.

A Girl In the River is told from the perspective of an eighteen-year-old girl named Saba Qaiser, who survived an honour-killing attempt by her own father and uncle. Saba was engaged to a young man with whom she wanted to marry, and had acceptance from most of her family, save for her uncle and father. One day, Saba ran off to a local court and got married to her lover. While at her in-law’s house, her father and uncle came and said, “Let us take her back to our home, and then you come take her honorably so neighbors and society don’t look upon us as a family that has been shamed.” They then brought her to the woods in a car and beat her, shot her in the face and the hand, put her in a sack, and threw her in a river. Even after such a brutal attack, she still managed to pull herself out of the river and found a local fuel station, where she was then taken to a hospital. Saba was determined to make examples of her father and uncle, saying, “I want them to be shot in public so that no other father [or] man does this to a woman and his family.” Although her father and uncle were put in jail, a loophole in Pakistani law allowed the complete release of the perpetrators if they received pardon from the victim’s family. In Saba’s case, the neighbourhood Elders said they would ostracize her in-laws if Saba did not forgive her attackers. She eventually decided to go to court and forgive them, but in the film she said to Obaid-Chinoy, “I forgive them because of family pressure, because of societal pressure. But in my heart, they will always be unforgiven.”

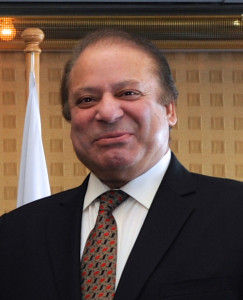

In Obaid-Chinoy’s acceptance speech, she mentioned that Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif told her that he would work on changing the laws regarding honour killing and eliminating loopholes that leave men unpunished for committing these brutalities. According to Sharif, honour killing “is totally against Islam and anyone who does this must be punished.” His goal is to make honour killings a crime against the state “at the earliest possibility.” Although the international recognition of this film is a huge step toward ending honour killing in Pakistan, one must question the feasibility of what Sharif is promising to Obaid-Chinoy.

Sharif and the rest of the Pakistani government seems to be thoroughly invested in the issue; he hosted a screening of the film in Islamabad and recently expressed “the government’s commitment to rid Pakistan of this evil by bringing in appropriate legislation.” Passing this legislation will be a long process, but progress has already been seen in Punjab, Pakistan’s most populous province. The Punjab Protection of Women Against Violence Bill unanimously passed on February 24, which redefined violence as any offense committed against a woman, including “domestic, sexual, psychological, economic abuse, and cybercrime.” In Punjab, two brothers were sentenced to death and fined for the honour killing of their sister and her husband, who got married out of their own will six years ago. This incident of holding accountability is an important step in changing a culture that has condoned honour killings for so long.

The lack of feasibility roots more from the religious parties in Pakistan. They have criticized the recent bill by calling it anti-Islamic, accusing the law for being one that “makes a man insecure” and attempts to liberalize the country. Mufti Kifayatullah, leader of the religious party Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, acknowledged that Islamic laws were misused to protect killers, but he still believes that “[r]emoving Islamic laws shall never be tolerated…The religious parties will not allow the government to solve the problem in this way.” The deeply-engraved ideologies in Pakistani society also defy the transformation. In A Girl In the River, Saba’s father told Obaid-Chinoy that he gained greater respect in the community for his attempt to kill his own daughter. He said, “Yes, I killed her. She’s my daughter and I wanted to kill her. I provided for her. How dare she defy me? How dare she go out without my permission? And I am ready to spend my entire life in jail because this is something I did for my honor, the honor of my family. She has shamed us.” Obaid-Chinoy saw that he did not see her as another human being; he saw her as an animal that he owned and could not make decisions on her own. The attitude of Qaiser’s father represents many other men who still believe they are entitled to the life choices of the women in their family, and feel they are fully justified to murder a woman if she goes against their wishes.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gk2OcKVu8qU&w=560&h=315]

There is still a long battle ahead before women like Saba Qaiser will find justice and protection against honour killing. If these legislations are passed as Sharif promises, it will be a watershed point in Pakistani history that will lead to a change of legal and cultural positions that function to protect women and prosecute the perpetrators of such inhumane gender-based violence.

HBO’s schedule to air A Girl In the River can be found here. McGill University is also screening the film; the event page can be found here.