A New Pink Tide in Latin American Politics

Over the past half-century, Latin America has witnessed three cross-regional political shifts. The region first suffered uprisings of extreme right-wing dictators and their military juntas during the 1970s. Following the victory of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela in 1998, the late 20th century to 2021 was marked by historical elections of leftist governments, sparking the “pink tide“: a political wave favouring the Left. After a decade of hegemony, widespread disenchantment with the Left benefited the Right in Latin America. However, the recent economic and health crises appear to be reversing the standing of the Right in the region. The electoral victories of the Left, defeating the extreme Right in Chile and Honduras, the advance in the polls of Lula over Bolsonaro in Brazil, and the election of the first left-wing Colombian president, herald a new trend. Marked with disillusionment, is the right-wing only drying up and giving way to yet another optimistic “new Left” in Latin America, or are we seeing a new, robust, and viable “pink tide?”

The rise of the first pink tide

Freed from a geopolitical stigma at the end of the Cold War, channels in Latin America opened for a left turn in the 1990s. Left-wing parties could grow without fear of being associated with a “Soviet beachhead.” The rise of the pink tide was a reactionary, transnational wave capitalizing on the long-term grievances of minority exclusion in Latin America and the harmful effects of neoliberalism economic theory. Neoliberalism was also associated with rising inequalities based on the belief that government interventions were detrimental to markets. Thus, the pink tide became a popular empowerment tool used to overcome neoliberal market discrimination and absorb the marginalized indigenous communities and the rural people.

In the context of today’s Latin American Left, both the distinct populist, radical Left and the institutionalized, moderate Left make up the pink tide. The radical members of the pink tide capitalized on grievances based on rural economic exclusion from neoliberal practices. They also denounced the political ineffectiveness of their countries’ electoral democracy in the context of massive inequalities, violence, and social exclusion. However, both approaches to left-leaning governments arose to fight corrupt elites, which the former far-right dictatorships, fragile clientelistic democracies of the region, and military junta had favoured.

Like today, a central ideological root of the pink tide was the wave of progressivism it embraced and defended. Indeed, in addition to the normalization of Indigenous parties that leaders such as Bolivian President Evo Morales advocated for, legislators put gender inclusion on the political agenda. Women previously deprived of a political voice became represented in governments. For example, Argentina was the first to adopt a candidate quota law to increase the number of women in the Argentine Congress. Thus, the emergence of the pink tide was widespread, propelled by long-term grievances of exclusion, with a legacy of greater recognition of minority groups and economic reforms to alleviate extreme poverty.

The return of the Right

The political shifts in the region have often reflected a tipping point between optimism and disenchantment with the government and an illusory hope for other alternatives in a vicious circle. In the first pink tide, governments benefited from a short-term primary commodity boom and could afford increased social spending. Unfortunately, standing as a temporary resource, the exhaustion of the boom led to widespread popular disillusionment. Since the 2010s, the Right has been able to use economic slowdown and perceptions of corruption on the Left to revive itself. In Brazil, the narrative of untrustworthy left-wing parties was powerful and at the core of Bolsonaro’s campaign in 2018. Thus, leftist governments, which engaged in cronyism, led to disenchantment with the Left—with good reason—and ushered in a shift to the Right in Latin America.

The election of the conservative Mauricio Macri in Argentina marked the right-wing governance shift, climaxing with the election of Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil in 2018. One of the very causes of the emergence of right-wing governments has been the contest of globalism, pictured as a conspiracy to impose unfair economic policy, advance a “cultural Marxist agenda,” and control populations by uprooting them from core values. Thus, it is by capitalizing on discontents with the Left that the Right’s hegemony has held for a decade. Through shifting dissatisfaction, the Right is losing its grip today.

The Left as an alternative to a failing Right

Just as it did 30 years ago, the return of the Left is spreading across regions through the same anger directed at inequality and corruption. The current political climate repeats the first pink tide: increasing poverty and inequality exacerbated by the pandemic have led to mass protests and growing hostility towards conservative governments. This “new pink tide” resembles its predecessor as a reactive movement reflecting the successes of gender ideology, farmers and indigenous mobilization, or feminist movements which have spurred in Colombia, Argentina, and Mexico.

Photo of Lula supporting Tierra Livre, which organizes cooperatives of family farmers by PCdoBnaCamara licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0

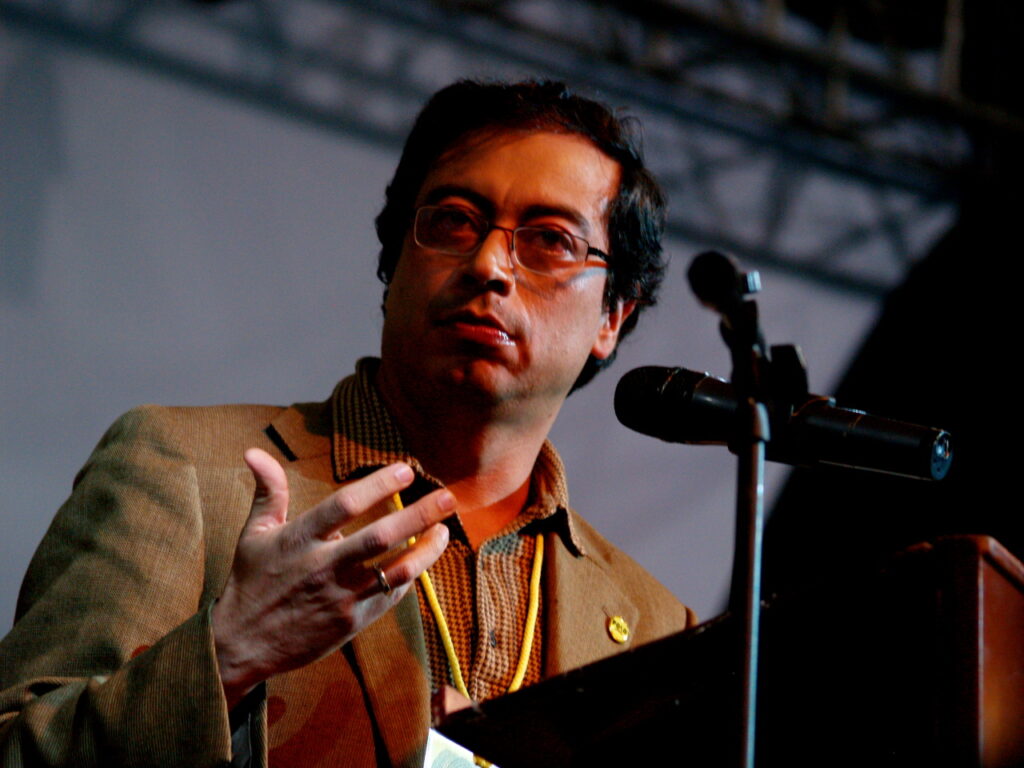

However, this time, no revolutionary ideological movement is countering the Latin American neoliberal doctrine. The population no longer seeks a new independent economic order nor emancipating from neoliberalism. Gustavo Petro is an example of the “new Left,” stating that “Colombia doesn’t need socialism, it needs democracy and peace.” The newly elected Colombian president tends to detach himself from the leftist political appellation as it is understood in the West, breaking away from the traditional Left and Right division, which caused harm to his country. The supporters of this new left-leaning governance are voters that “simply wanted a better life for themselves and their children.”

To this end, COVID has made the right-wing irrelevant in Latin American regions as protestors confront their government’s mismanagement of the pandemic. In a right-wing milieu without social safety nets, Latin American voters are driven to support candidates who promise big government and more social spending.

Bolsonaro represents the decline of an obsolete right-wing unable to respond to a global social crisis. Indeed, his struggle against globalism reduced the gigantic agro-businesses exports of his country, and his skepticism towards COVID and masks contributed to the country’s COVID-19 deaths. Moreover, Brazil’s heavy reliance on Chinese-made vaccines substantially negatively impacted vaccination, worker health, and the economy. As a result, under 20 per cent of Brazilians approve of Bolsonaro, legitimizing the Left as a viable alternative. The same is true for the victory of the Left in Colombia, where Petro benefited from the significant unpopularity of the conservative Ivan Duque, who had a disapproval rating of 77 per cent.

The wave of leftist governments settling across all of Latin America is indisputable. Sharing the same cries of inclusion, progressivism, and social justice as two decades ago, many perceive this political shift as a new massive pink tide. Evolving in a non-revolutionary context ideologically speaking, lacking a “populist” Left in the manner of Hugo Chavez of the 2000s, this wave propelled by the COVID crisis and the need for social safety nets diverges somewhat from the original pink tide movement. However, political change in the region has often reflected the vicious cycle of the incumbent governments failing to meet high expectations. Today, environmental and economic difficulties will be the challenges these leftist governments will face. It is perhaps too early to tell if these newly elected left-leaning governments will successfully hold power long-term, or if they will be ousted in the next cycle by the Right.

Featured image: Pink lake by Artem Zykin is licensed under Pexels

Edited by Joshua Poggianti