A Rocky Road to Peace: Syria’s Failing Ceasefires

As Syria prepares to enter its 8th year of civil war, the situation in Eastern Ghouta, its southwestern region, suggests that not much progress has been made. In just this past week, around 530 citizens in Damascus’ last rebel-held suburb died, while roughly 2,500 were wounded; the dreadful scenery was described by UNICEF Executive Director Henrietta Fore as “hell on earth”.

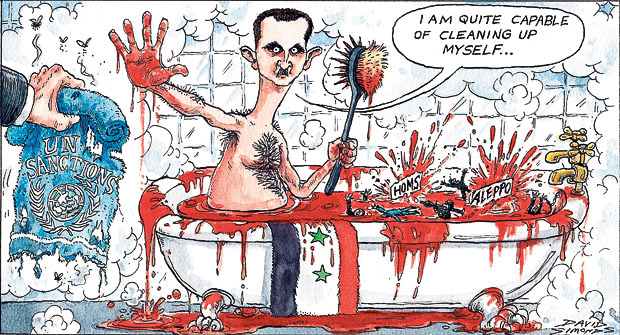

This worrying portrayal of what could be some of the worst violence seen since the start of the civil war has been heavily critiqued by human rights groups, denouncing the lack of initiative taken by the United Nations and allies of the Syrian war to help endangered citizens. Recently, the United Nations Security Council spoke out against these atrocities by calling for an immediate 30-day ceasefire, intended primarily to allow the delivery of humanitarian aid and medical assistance.

However, following a lengthy implementation, the resolution ordering a ceasefire yielded no results. Despite an agreement, fighting has, in fact, erupted on both fronts. On one side, the Syrian government asserts they are targeting terrorist groups who broke the truce first, while the rebels claim to be responding to regime attacks through firing mortar shells on the other.

While the UN hoped to create a safe corridor for civilians to leave, families from Eastern Ghouta find themselves trapped in the midst of intense fighting. Solutions are continuously discussed by international actors in Security Council sessions to mitigate fighting and protect Syrian civilians. However, based on the UN’s past efforts, quite often long-term resolutions and temporary ceasefires fail to be successful. In fact, ceasefires implemented to address the Syrian war are extremely fragile and are often disregarded in the days following their implementation.

Before delving into the cracks of failed resolutions, it’s crucial to understand the mechanisms of peacekeeping operations (PKOs). Beyond monitoring ceasefires, PKOs use a range of tools to facilitate a country’s road to peace. To execute this arduous task the UN deploys carefully selected personnel, which differ in size and composition depending on the operation, to enforce PKOs. Personnel for these operations can range from armed military troops and police units to unarmed observers. For instance, in Sierra Leone, military troops and police units have used various disarmament tactics to both reduce the capacity of factions to commit violence and to signal strong commitment towards civilian protection.

Furthermore, observer personnel also occupy a prominent surveillance role in ceasefires by reporting on real-time events. Even though observers do not possess the capability to protect civilians or intervene in violence, they do report on ceasefire violations so that subsequent repercussions can be enforced. In practice, however, observers have failed to produce favourable results. In the early stages of the Syrian war, 300 blue helmet observers were sent across Syria to monitor the implementation of the ceasefire from both government troops and rebels. Despite this, as opposed to mediating violence in the region, observers actually became a source of conflict and increased violence.

While factions were threatened by the presence of UN mediation, civilians also mistakenly sought safety in observers in the midst of fighting and endangered their lives by travelling through war zones. The ceasefire was in fact marred by so much violence that observers were unable to do their work. As a result, the UN decided to pull out observers from Syria, making it near impossible to place responsibility on an actor in the event of a ceasefire violation.

Furthermore, although the presence of police units, military troops and observers on the ground do signal a serious commitment to a certain conflict, influential decisions in these PKOs lie in the hands of delegates of countries disconnected from direct hostilities and civilian deaths. Previous ceasefires have in fact evolved along strict political axes and combined efforts between the United States and Russia, who, albeit as allies to opposing factions of the war, are currently seeking common ground and taking the lead on providing a political solution to the Syrian crisis which matches the interests of their respective allies.

In September 2016, following a first attempt at a ceasefire in February, Russia and the United States reached a second and “final” agreement regarding the conflict. The deal proclaimed that if Russia were able to pressure Syrian president Bashar al-Assad to respect the ceasefire for a week, the US, in turn, would set up a joint coordination unit with Russia to begin air strikes against terrorist groups active in the Syrian war. However, the resolution was subject to an important loophole — attacks against terrorist groups were not included in the ceasefire and thus weren’t subjected to constraints. As a consequence, the ceasefire was poorly adhered to by the Syrian government and airstrikes and aid blockades in rebel-held areas persisted.

Unfortunately, this narrative similarly remains in Eastern Ghouta today. While the United Nations urges both parties to respect the ceasefire and allow humanitarian aid to reach civilians, the Syrian government has manipulated the exclusion of terrorist groups from ceasefire agreements to conduct persistent attacks on rebel-held enclaves. Moreover, Syria’s ambassador to the UN recently stated plainly that “the fight against terrorism would continue regardless” and that attacks launched during the ceasefire served as a response to violence resulting from terrorist groups. Rebel factions on their side agreed to the truce and facilitated aid access, but also vowed to respond if attacked.

The tensions that arise in temporary ceasefires highlight an intrinsic structural problem that makes these resolutions more fragile than most. Indeed, temporary ceasefires presuppose an ending period where both parties will have an incentive to adopt an offensive tactic in preparation for renewed fighting. Both sides are evidently aware of this danger and have equal motivation to move against their adversary. As tensions between both parties increase, ceasefires begin to unravel and it becomes nearly impossible to determine who broke the truce first. As a consequence, ramifications for disobeying the ceasefire cannot be applied and the credibility of such a resolution lowers significantly.

If a ceasefire were to be effective in Eastern Ghouta, UN delegates must not only mediate the conflict and various attacks but also clearly articulate the consequences of such violations. Ceasefires succeed when they outline a concise roadmap for future negotiations, whilst establishing a mechanism to report violations and address such infringements.

Lastly, it could be argued that ceasefires embody simplistic band-aid solutions to a greater conflict, which can only be solved with long-term peace settlements in between all actors of the Syrian war. Suzanne Werner asserts that the resumption of conflict often stems from the failure of settlements to resolve the underlying issues at hand, and instead propose an incomplete solution which does not eliminate the source of conflict and provides the conditions for further hostilities. As ceasefires continuously fail to protect civilians and enforce a peaceful environment, their ability to yield long-term results or even prompt effective peace agreements is greatly challenged. Instead, as Werner suggests, ceasefires propose a simplified and often rushed solution to what often is an extremely complex and multifaceted conflict.

The ceasefire proposed for Eastern Ghouta ultimately possesses none of the aforementioned traits and instead provides little information as to when the ceasefire will begin or how it would be enforced on all factions. With a crumbling structure and a lengthy implementation process, one questions whether this month’s ceasefire will produce favourable results or long-term peace outcomes, leaving Eastern Ghouta’s 400,000 habitants unprotected and neglected for an eighth consecutive year.

Edited by Alec Regino