A Tale of Race in Two Nations

This year, France and the United States have both reckoned with their own respective issues of multiculturalism and systemic discrimination. In the US, the country was rocked by Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd. Simultaneously, in France, the American BLM movement reignited protests over the death of Adama Traoré, who passed away in 2016 under circumstances of police brutality eerily similar to Floyd’s. Yet, the dialogue surrounding these two issues is very distinct. Race has long played a role in the US discourse, from politics to culture, whereas French Republicanism has fostered a more “colourblind” approach, where conversations about class tend to dominate. Intertwining our own personal experiences — Max’s experience as a half-Indian American and Amy’s as a French citizen — it is fascinating to explore these distinctions between two cultures, and the reasons behind them.

Amy’s Story

Born and raised in a French household, I expected some level of culture shock when I immigrated to Canada. The architecture, the food-culture, and the weather were things I knew to brace for. What I didn’t expect, however, was the shock I felt when confronted with the way social issues were articulated. I’d never seen so much of the prevailing political discourse articulated around race. North America had finally stumped me. I asked myself: Does everything come down to race here? Through conversations with my French peers, I realized that I wasn’t the only Franco-European experiencing some level of discomfort from this. One friend revealed that these conversations made him so uncomfortable, he’d taken to exclusively befriending other French people, just to avoid them. These discussions laid bare that I’d never had an honest, candid conversation about race.

And while this has everything to do with me being caucasian, my complete and utter lack of exposure has system-level implications. This is mainly because race is not the medium around which the French media, political establishment, and intelligentsia, frame social issues. Rather, social issues are articulated primarily around class, with race being considered an unspoken extension of class. Whenever race is brought up in the French media, the majority of commentators, and (mostly white) French viewers, shun race as a non-issue, sticking uncritically to the idealistic notion of French colour-blindness.

By and large, the only people in France who orient political discussions towards issues of race are minority populations — the very same people these issues affect. After the traumatic images of George Floyd’s murder surfaced in May 2020, it was the Franco-African community that first rallied in protest in France, led by none other than Assa Traoré, the sister of Adama Traoré. Her mission is to raise awareness of racial discrimination in a country that refuses to acknowledge race. Meanwhile, the non-minority French people in my community reacted to France’s BLM movement with confusion and, often, defensiveness. I was told: “France doesn’t have a race problem,” or, “We’re not half as bad as the US.” This view was further abetted by the mainstream French media framing BLM protests as an “American uprising” within France. This isn’t our issue; it’s theirs.

Max’s story

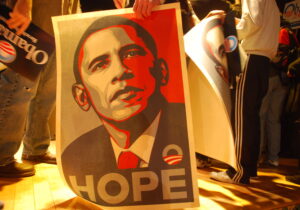

As a half-Indian American, the topic of race has had a constant presence throughout my life. Growing up in Westchester, New York, race was often discussed with my family and schoolmates. From my mother’s experiences of racism to the celebration of our backgrounds in elementary school, race actively shaped our conversations. Barack Obama’s election as our first African-American president was hailed as a confirmation of how far Americans had come from the country’s racist past.

However, my rosy outlook on US race relations came to an abrupt end when I returned to the USA in 2014 after four years abroad. I was immediately confronted by the Ferguson protests following the shooting of Michael Brown, and began to recognize the plague that is police brutality. I discovered that the reason my high school was far whiter and less diverse than my previous school, despite only being a mile away, was because New York’s public education system is the most segregated in America. And once the 2016 Presidential Elections came around, it became clear to me how much of an influence race played in US politics; turnout of African-Americans, racial resentment of white Americans, and the volatility of the vote of Hispanic Americans were all key discussion points in our politics. Class, though important, was largely marginalized by the issue of race, even more so with candidates such as Donald Trump, who actively made overtly racist statements.

When I gained several French friends upon coming to McGill, they were flabbergasted by the way I casually broke up US politics into racial blocks. I was shocked when a friend asked, “But isn’t talking about how different races vote kind of racist?” To me, the role of race in politics was a key legacy of the racial disparities from American history and a reminder of our inability to close those gaps. Yet for my French friends, my candidness over race and racial issues came off as uncouth at best, and offensive at worst.

Why/Pourquois is it this way?

Why is Max’s racialization so offensive to French ears? Because, in general, the French intelligentsia has cultivated the notion that race, as a concept, is racist in and of itself. To differentiate on the grounds of race flies in the face of laïcité, France’s unique brand of secularism, which is meant to preclude discrimination on the grounds of race, religion, and ethnicity. Under the banner of laïcité, all are full and equal citizens who voluntarily identify with France’s Republican values. Race is meant to be invisible, and the only community French citizens belong to is that of the nation. Recognizing another is to betray the French ideal. As a result, discussions of class have primacy in academic and political circles when articulating social issues. Across both sides of the political aisle, race is largely considered the thrust of “American-style” political discourse.

In contrast, while colour-blindness dominates the intellectual conversation in France, it has been largely criticized in the US by the academic community. Structural deficiencies in education, housing, and income between white and non-white Americans continue to be staggering. “Not seeing colour” did hold some sway after Obama’s election to the presidency in 2008, since some reasoned that if we had elected a Black president, racism was not an issue anymore, and that perhaps the US had entered a “post-racial” age. Yet this mirage would be broken by Obama’s “birther controversy” and Donald Trump’s xenophobic campaign, demonstrating racism was alive and well. Movements such as the George Floyd Protests have further undermined the “colourblind” approach.

How a nation addresses the topic of race speaks directly to how it has reckoned with its history of systemic racism. In the US, there is a very frank acknowledgement of the role race has played in its history. From the Native American genocide, to slavery, to the three-fifths compromise, the US has constantly grappled with how to reckon with its large minority population. Its largest political battle in the 20th century, the fight to pass civil rights legislation, was a racial issue. And while the post civil-rights era experienced a current of racism-denial (by 1998, 64 per cent of white Americans dismissed racism as an actual hindrance anymore), protests and riots have consistently thrust the issue back into the spotlight, ensuring it never fully leaves social conversations. In contrast, France has largely dodged reckoning with its colonial legacy. While the effects of its imperialist past are still highly tangible in modern society, embodied by profound structural inequalities and continued racial discrimination, France’s response has mainly been to ignore race altogether and embrace an idealistic colour-blind Republic. President Emmanuel Macron has sworn to be unrelenting in his mission to end racial discrimination, yet he has refused (as have previous administrations since 1978) to include racial, ethnic, and religious statistical categories to the national census. How can the government combat something of unknown proportions? Race and racism are rendered immaterial, and racially-based inequalities remain consigned to the realms of class-inequality. This isn’t the case in the US, where the important role played by racial blocs in political coalitions has doubled down how often race gets discussed. Race heavily factors into how people vote, especially because race is such a strong determinant of socio-economic status. As such, Americans are keenly aware that race is an important consideration.

Conclusion

The US and France are undoubtedly distinct; systemic racism towards BIPOC citizens has not taken the same course in these two countries. However, France and the US have a shared history of having large minority populations as a direct legacy of their colonial pasts. It is important, in both cases, to reject colour-blindness as a solution to racial inequalities. While Donald Trump’s rhetoric illustrates the case against sweeping racism under the rug, France has arguably not yet reckoned with race in the same way. Its insistence on casting off racial considerations in favour of class doesn’t so much represent a renunciation of racism, but rather the erasure of racial minorities. This willful ignorance stands in the way of effectively addressing the country’s systemic racism. It is pressing among both nations to realize that racism remains alive and well, and the only path forward is to recognize it as such, and begin addressing racial divides.

Feature Image: USA raised fist, protest concept & France raised fist, protest concept by Jernej Furman is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Edited.

Edited by Clariza Castro