Access, Consent, and Sovereignty: Why the Resistance to Coastal Gaslink is About More Than LNG

Western Canada has been hankering for a new pipeline. Transporting crude oil and Liquid Natural Gas (LNG) to the coast allows for increased exports to countries other than the US – where demand has been drying up – and solidifies Canada as a world supplier of energy. Following a boom of LNG consumption in Asian markets, a flurry of proposed projects for pipelines and export terminals have been put forth to connect the massive northern LNG supply to the East Pacific. Crude oil, typically from the Alberta Tar Sands, is currently sold to the US at less than world prices while a smaller margin is shipped west, again to Asia. As the face of global energy shifts, Canada’s industry future relies on accessing world markets and foreign investments in LNG projects have shown that some at least are interested.

But reaching world markets has proven to be less an exercise in economics and more a lesson in understanding the values of all the people who stand to be affected. Few proposed pipelines have been built in the last decade. The environmental and cultural impacts of such projects created ardent opposition, primarily from local First Nations and environmentalists. TransCanada’s Energy East Pipeline, slated in 2013 to carry crude oil from Alberta to New Brunswick, cancelled after being deemed unfeasible following delays from opposition by the Assembly of First Nations of Quebec and Labrador, the Iroquois Caucus, the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs, the Grand Chief of Treaty 3 and the Kanehsatà:ke Mohawks. The Keystone XL pipeline, an expansion of the existing Keystone system reaching from Alberta to the southern US, underwent a series of protests, delays, more protests, rerouting, lawsuits, rejections, re-negotiations, and is currently halted due to an insufficient review of climate impacts. Embridge’s Northern Gateway would have carried diluted bitumen from Alberta through the Great Bear Rainforest to British Columbia’s northern coast, but the Coastal First Nations alliance fought legal battles to protect the sensitive ecosystem from tanker traffic, and the project was eventually quashed by the federal government. More recently, the twinning of Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain pipeline carrying bitumen from the Tar Sands through to the coast faced constant opposition from environmental groups and communities and, despite being bought by the federal government, has been halted on grounds that they failed to properly consult with First Nations.

(https://flic.kr/p/pPqJ7P)

There is a common theme in these examples: steadfast opposition from Indigenous peoples defending their traditional lands – although it is important to note that not all First Nations have opposed the projects, many have welcomed them and the economic prosperity they bring.

Coastal Gaslink (owned by TransCanada) seemed to have navigated through opposition. Taking natural gas from Dawson Creek (northeast BC) 670 km to a not-yet-built facility near Kitimat (on the coast), the pipeline was proposed in 2012, issued an Environmental Assessment Certificate in 2014, and reached an agreement with all 20 elected leaders of the Indigenous bands along the route. However, pipelines have never been just about pipelines.

More Than a Box to Check

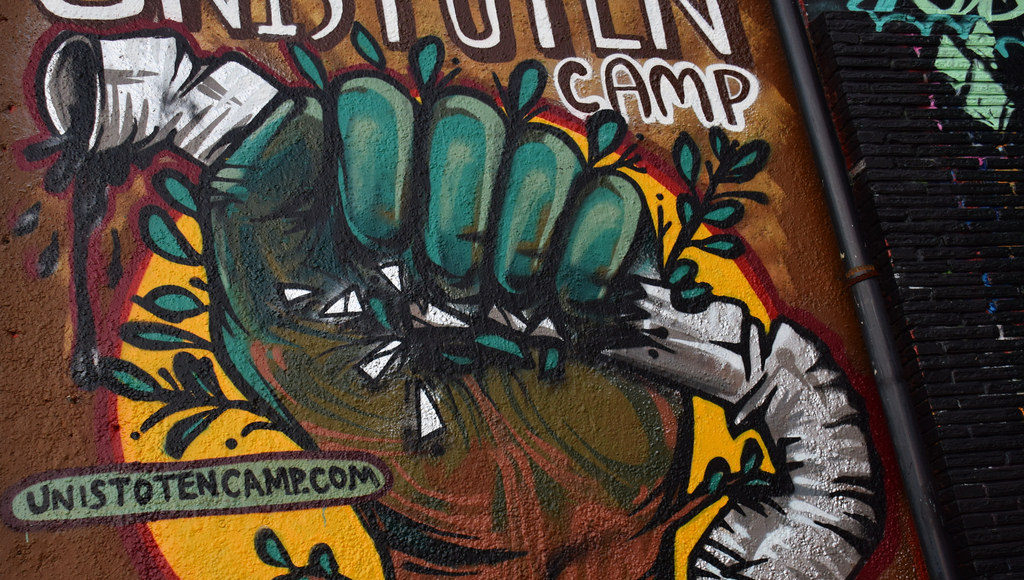

The Unist’ot’en are one of five clans making up Wet’suwet’en First Nation, living within a 20,000 km² territory in the central interior of British Columbia. Much of the land is unceded, meaning that a court has ruled that the Wet’suwet’en never gave up title to the federal government. In 2009 the Unist’ot’en set up a checkpoint on Morice River to control access into their territory, access that can only be gained with consent from Hereditary Chiefs according to traditional law. While the elected council of Wet’suwet’en had approved Coastal Gaslink, which runs through the unceded territory, the Hereditary Chiefs had not, arguing they had never been consulted. Coastal Gaslink workers were denied access, an injunction was filed to open the checkpoint, and on January 7 the RCMP broke through the Unist’ot’en blockade and arrested 14 people. Assisted by a Tactical Response Team, the display of force from the RCMP was the latest in disproportionate attention aimed at First Nations people. A temporary agreement has since been reached allowing access, but Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs are vowing that they will not permit a pipeline through their territory.

(https://www.flickr.com/photos/unistoten/8223656688/)

“Our medicines, our berries, the wildlife, the salmon, the water, the air we breathe, a lot of those are not replaceable,” she said. “If they destroy those and wipe out those species then they are wiping out our food and our way of life.”

– Freda Huson, spokesperson for the Unist’ot’en

The confusion stems from the fact that Elected Chiefs and council are a separate system from Hereditary Chiefs. Since time immemorial, the Hereditary Chiefs inherited their title and were tutored from childhood on the laws and customs of the community. Wet’suwet’en Nation has 13 Hereditary Chiefs who are considered to have jurisdiction over the wider traditional lands where Coastal Gaslink would cross. The elected Chief and Band Council is a product of the Indian Act of 1876, which was, at its core, a document designed to assimilate indigenous people into Canadian settler society. Today elected leaders are an integral part of many First Nations’ decision making and, as in the case of the Wet’suwet’en, work together with the Hereditary Chiefs. However, in what some are calling ‘the path of least resistance’ Coastal Gaslink only made an agreement with the elected council, who only have jurisdiction over the reserve itself. Demonstrating the incompetence of corporate regulation, Coastal Gaslink confirmed they did not consult with the Unist’ot’en because they were not identified by the provincial government as a governing body.

Whose Laws are These Anyways

Disagreement within Wet’suwet’en Nation is not the cause of crisis. Disagreement happens at all levels of governance everywhere. The arrests at Morice River were a symptom of the inability of the provincial government to respect First Nations governance and authority. Unist’ot’en people may have broken BC law when they defied the injunction, but RCMP officers broke Wet’suwet’en law when they entered onto Wet’suwet’en territory without permission. This is a legal pluralism seen since Europeans ventured west, with only one side facing penalties for their transgressions. Coastal Gaslink’s lawyer Kevin O’Callaghan argued in the injunction hearing that the leaders of the Unist’ot’en camp had not joined in consultations, constructing the blockade as a ‘self-help remedy.’ At a rally before the hearing Unist’ot’en camp founder and spokesperson Freda Huson reminded the crowds that no company representative came to the Unist’ot’en feast hall, where important decisions are heard and made. The laws of British Columbia are meant to serve its citizens; failing to reconcile traditional customs leaves a significant group disadvantaged.

As a non-native person, understanding the intricacies of Indigenous governance as its been complicated by centuries of colonial violence is not easy, nor is there a one-case-fits-all explanation. I certainly cannot claim insight into how Wet’suwet’en decisions are made. Nonetheless, recognizing that other systems have been in place since before Canada was a nation can help in appreciating the challenges First Nations communities still face.

(https://flic.kr/p/w6pCs3)

The events of January 7th have earned condemnation from across Canada. While the RCMP review their actions, First Nations leaders in BC voice their support of the Wet’suwet’en and many cities, including Montreal, have held marches in solidarity. Overt colonial violence is no longer tolerated in the public eye, but legislative protection is lagging. Many protesters and supporters have quoted Article 10 of the United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People: ‘… Indigenous people shall not be forcibly removed from their lands or territories.’ However, UNDRIP is not law in Canada. When it was written in 2007, Canada was one of four countries to oppose the declaration. Then-premier Steven Harper objected to the assurance of ‘free, prior, and informed consent’ regarding the use of indigenous territory, concerned that it would allow First Nations to veto development projects – in the same situations that are occurring in Wet’suwet’en territory.

A New Attitude

Justin Trudeau’s federal government has since embraced UNDRIP, but despite meeting with Indigenous leaders and communities to hear their concerns, little concrete action has actually been done. In 2015 MP Romeo Saganash put forth a bill (C-262) that would ratify some aspects of UNDRIP into Canadian law, but the bill is currently waiting to be read in the Senate and has not been touched since May 2018. Had C-262 been passed, judging the actions of Coastal Gaslink, the RCMP, and Unist’ot’en protesters would be much easier.

Is there a place for a new pipeline on the West Coast? Many people, including several First Nations leaders, concede that there is. Coastal Gaslink has promised $6 Million in conditional work contracts towards constructing the pipeline to First Nations along the route, investment that helps bolster opportunities for future generations. However the process of deciding on a project is not a simple one, nor should it be. As well as the inherent environmental risks and impacts from transporting oil or gas, the vast tracts of land involved contain a diversity of culture that cannot be overridden in the name of development.

Any community or municipality in the route of a proposed pipeline has to find a balance between environmental protection and economic benefit. That decision must be made by the people most directly affected, in the manner they see fit. First Nations and advocacy groups are increasingly raising dissent to trespassing, and as the record of cancelled projects show, they are gaining ground. Until corporate planners realize theirs are not the only rules that count, British Columbia could be waiting for their pipeline for a long time.

Edited by Kody Crowell