America’s Black and White Response to Drug Epidemics

Up until recently, the caricature of the typical drug user has often been painted as a person who suffers from their own moral failings. When the burgeoning crack epidemic was at its peak in the 1980s, the predominant response was to “lock them up” referring to incarcerating any addict or supplier affiliated with the trade. Thirty years later, the US government has a starkly different solution to a similar issue. The opioid epidemic is deepening its claws into the US— it could claim 1 million lives by 2020. Unlike the ’80s, however, the government is striving to eradicate its addiction problem through a different means: a health-based approach.

The 1980s in the United States were characterized by Madonna, bell bottom pants, and the revitalization of the War on Drugs by President Ronald Reagan. Harsh measures against illegal drug use manifested themselves through tougher penalties, increased government spending in anti-drug enforcement programs, and through the passing of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act by Congress in 1986. This act created mandatory minimum sentences for individuals found guilty of possessing above a determined amount of cocaine. A “100-to-l ratio between powdered cocaine and crack cocaine” served as the guideline for mandatory minimums. For example, the same minimum penalty of 5 years was administered for 5 grams of crack cocaine and 500 grams of powdered cocaine. Due to the lower price and easy accessibility of crack cocaine, it was consumed more by African-Americans while wealthier, white Americans consumed the powdered version more. The policies passed were all similar in nature as they criminalized the manufacturing, trafficking, and consumption of illegal drugs like crack cocaine, disproportionately impacting African-Americans.

Overall, the response to the crack epidemic was far from health-oriented, as it disregarded the mental and physical health of citizens over the villainization of their addictions. The media perpetuated a violent image of African-American men involved in the crack epidemic, which Rachel Godsil, the co-founder and director of research at the Perception Institute, found “exceedingly hostile”. These policies resulted in the mass incarceration of African-Americans at alarmingly high rates. The harmful legacies of the War on Drugs can be observed by the overcrowding of prisons in the US where, although “African Americans and Hispanics [made] up approximately 32% of the US population, they comprised 56% of all incarcerated people in 2015.” At the federal level, almost half the prison population is comprised of drug offenders. Although overall drug use is equal among black and white demographics, Human Rights Watch discovered that black people are more likely to get arrested and face 13.1% longer sentences than their white counterparts.

As one fast forwards into the era of skinny jeans, Beyoncé, and a starkly contrasting approach to drug policies in 2018, it is clear that the discourse regarding drug addiction has shifted. The current health crisis centred around opioids has killed over 42,249 Americans in 2016 alone and over 500,000 people since 2000. Opioid prescriptions increased from 112 million in 1992 to 236 million in 2016. The dependence and indulgence of the misuse of opioids have led to a historically fatal health crisis. This epidemic is fueled by the growing pressure on doctors from pharmaceutical companies to overprescribe opioids. The misuse of this drug in the United States was highlighted by the 2016 surgeon general’s report, as “only 10% of people suffering from drug addiction get speciality treatment,” creating a breeding ground for the current crisis. It has grown so out of hand that in October 2017 President Donald Trump declared a national public health emergency, recommending a contemporary War on Drugs. This status “expands access to telemedicine in rural areas, instructs agencies to curb bureaucratic delays for dispensing grant money and shifts some federal grants towards combating the crisis.”

Unlike the War on Drugs in the ’80s, contemporary drug policies focus on rehabilitation from addiction, a more compassionate stance on drug abuse. Michael Botticelli, President Barack Obama’s former drug czar, stated that “we can’t arrest and incarcerate addiction out of people.” Newer, health-focused strategies were exhibited by the 21st Century Cures Act passed by Congress, which invests $1 billion toward addiction treatment over two years. The language used to describe addicts is not riddled with negative connotations such as “crackhead”, “junkie” or even “super predator”, but rather portrays the users as victims. Chris Christie, former New Jersey Governor and head of the Trump’s opioid epidemic commission, stated that “We need to start treating people in this country, not jailing them. We need to give them the tools they need to recover, because every life is precious”, heavily contrasting the harsh “tough on crime” bipartisan stance that prevailed during the crack epidemic. This raises the question: why are the remedies to the two drug epidemics so vastly different?

There are several aspects to examine when answering this question. The first concerns the legality of the drug. It is important to note the legal differences in possession. Opioids are drugs often prescribed by doctors. Once prescribed opioids lose its potency over time, or when addicts lose their prescriptions, however, they turn to fentanyl and heroin, two illegal opioid drugs. On the other hand, crack cocaine is a hard-to-obtain narcotic. At its peak of the epidemic, there was a high degree of gang violence and murders through the transportation and sale of the drug. Therefore, the harsh laws instituted could be arguably justified in order to further deter illicit drug trade.

However, a frequently overlooked explanation for the drastically different responses is the race of the victims. The main victims of the opioid epidemic are white Americans. Before this crisis, racial minorities were often stereotyped as the archetypical drug addict. However, recent surveys reflect a change in an attitude among Americans from addressing addiction as a crime to treating it as a health concern. The change in the race of the victims has played an integral role in causing this change.

A 2009 psychology study conducted by Xiaojing Xu, Xiangyu Zuo, Xiaoying Wang and Shihui Han illustrated the impact race can have on evoking sympathy. The researchers discovered that “when participants looked at images of people in pain, the parts of their brains that respond to pain tended to show more activity if the person in the image was of the same race as the participant.” This study shows that a “shared common membership” with the individual subject to the suffering is more likely to evoke empathy. Therefore, due to this racial bias, the majority of Americans are more empathetic towards opioid addicts, because the epidemic largely impacts white people. These biases may explain why there are more compassionate measures taken to eradicate the opioid crisis when just several decades prior there was little institutional support for drug addicts.

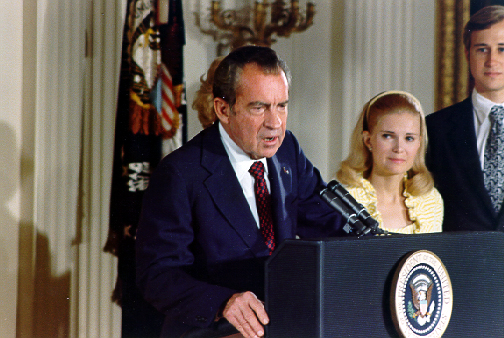

Moreover, there is considerable evidence that the War on Drugs was racially charged in its conception. A 2016 statement by Nixon aid’s John Ehrlichman explicitly states how, “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people.” Ehrlichman goes on to further assert that Nixon’s War on Drugs was a targeted effort and that by “getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news.” This statement shows the brutal truth about the corrupt, racist origins of the War on Drugs in the 1970s. When crack cocaine addiction largely impacted African-Americans, the clinical militarized approach was implemented to further damage black communities.

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people […] By getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news.” – John Erlichman, White House Domestic Affairs Advisor (1969-1973)

Despite the fact that it was drug abuse that was branded “public enemy number one” over 40 years ago, it is not the drugs alone that shaped perception and policy. The notion of race and ethnicity associated with drug addiction adapted alongside the changing onus of addiction. The opioid crisis exemplifies the fact that there is no true archetype for an addict. Victims of opioid abuse are upper-class and white, which runs counter to the traditional clichés associated with drug addicts. These drug users are sheltered from the government’s racist policing strategies, mandatory minimums and its enduring consequences on the justice and prison systems. Although there is still much progress to be made to adequately address addiction as a health problem, victims of the opioid crisis are receiving the compassion and policy changes that crack cocaine addicts in the ’80s could have never imagined. It is improbable to think that America would have the same empathic response if the victims of the opioid crisis were black.

Edited by Alec Regino