“Antiestablishmentarianism”: A Big Word for a Small Factor in the Future of U.S. Elections

In the wake of the Iowa caucus and New Hampshire primary, there seems to be a myriad of articles on varying topics about the 2016 election flooding all forms of media every day. Their discussions range from policy proposals and campaign promises to coughing fits and bathroom breaks. However, an important yet often neglected question revolves around the long-term effects of the 2016 presidential election. How will political analysts in 40 or 50 years see the 2016 election? What meaningful changes will these next 10 months have in store for the American political future?

There has been much talk about polarization and challenges to the “political establishment” this election cycle. As we’ve heard talk — and seen examples — of massive political polarization occurring in the American political atmosphere since the 1970s1, it has led political pundits and analysts to question the future of party structure and party alignment in the United States. This leads us to the following question:

Will the anti-establishment GOP candidates for President — Ted Cruz and Donald Trump — usher in a new party system?

The answer is no.

Since the founding of the United States, the country has seen five or six party systems, depending on whom you ask. These party systems are separate political eras wherein different parties, ideologies, and party identifications have aligned in new ways, each system ushered in by a new reformist way of thinking. The current debate regarding party systems is not a rejuvenation of the “has a sixth party system been created after the Civil Rights Act in 1963” question. Instead, the discussion playing out in the past two years has been about the future of the Republican party and the American political landscape.

There is genuine concern within mainstream media and high rank-and-file politicians about the potential GOP split. Patrick Healy and Jonathan Martin write in the New York Times, “[w]hile warring party factions usually reconcile after brutal nomination fights, this race feels different, according to interviews with more than 50 Republican leaders, activists, donors and voters, from both elite circles and the grass roots.”2

Although these concerns and fears of a GOP split are seemingly quick and reasonable conclusions one would draw from the chaos occurring within the Republican Party, a closer analysis renders the bases of this type of conclusion unfounded and illogical. Instead, it can be concluded there will neither be a GOP split nor a massive political realignment after the 2016 election for two reasons. Firstly, the very polarization in Washington driving the anticipation of a GOP split will in fact make such a schism impossible due to the inflexibility of party choices in the American two-party system. And secondly, realignment requires by definition changes in the voters’ demographics based on race, religion or region; these changes have not occurred during this election cycle. Instead, there is only antiestablishmentarian rhetoric originating from Trump, Cruz and others, which per se lacks the power to realign party politics since it permeates virtually all group divisions in the U.S.

1) Polarization’s opposite effect

Firstly, the wide gap between the strongly divergent ideologies that is making people question party endurance is what will keep the parties together.

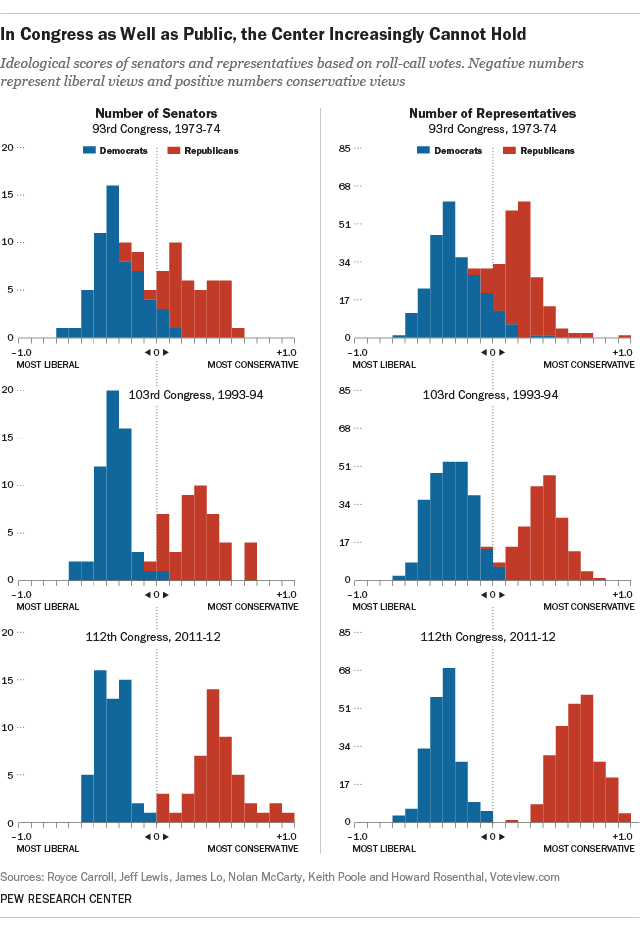

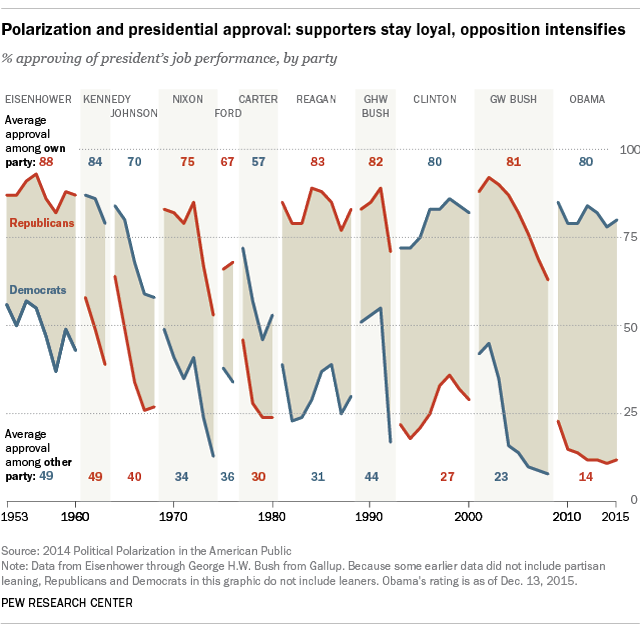

Since the 1970s, ideological polarization in the American political landscape has been well documented. Never before has such a clear divide been drawn between Republicans and Democrats. Presidential approval ratings based on party have become increasingly divergent since Eisenhower’s administration.3 The number of Americans who describe themselves as “consistently conservative” or “consistently liberal” has doubled in the past two decades.4 The proportion of the electorate self-identifying as moderate is drastically shrinking.5 And these political attitudes of the public have been translated into seats in Congress, reducing cross-aisle cooperation.6 Polarization of American politics is evident, to say the least.

Such chronic divergence in all political aspects of U.S. politics diminishes the American principle of compromise in government. As such, when pundits speculate that antiestablishmentarian candidates like Trump or Cruz might encourage creation of a new party, they are ignoring the fact that the radical rhetoric of these candidates is not intended to bring a new party; instead, Trump and Cruz’s messages serve to further polarize the political atmosphere. With increased radical positions within the Republican party, the party will be motivated to move more to the right to attract Trump and Cruz supporters. In this way, chances of realignment become slimmer as the Republican and Democratic parties drift even further apart rather than give way to a new coalition of voters composing a new party. In other words, there would be little chance of cross-aisle migration to allow a realignment process.

When such a large gap between Republicans and Democrats develops, contrary to what Healy and Martin argue, the GOP will not split into two new parties. Instead, deeply divergent factions will develop within the GOP. These two factions between establishment and anti-establishment voters will ultimately doom the party. They will jeopardize any chance of a right-wing candidate achieving office because the finite number of conservative-leaning voters would have to choose between the two factions of the GOP; few moderates or liberals would brave crossing the wide intraparty gap and migrate to one of those factions so that it has any chance at achieving a majority; and any national Democratic candidate vying against a Republican would be a shoe-in. In the end, Democrats will dominate national politics until the right-wingers figure out how to unite again. Thus, even the most stubborn-headed Trump or Cruz supporters should be able to realize that a split in the GOP would be disastrous for all conservatives in the United States. Whether this realization will translate into action is an entirely different question, however.

2) Absence of concentrated catalysts

Secondly, two factors make it so no new cleavages will develop along the lines of anti-establishment politics: a lack of a true catalyst to trigger party realignment and the spread-out nature of the anti-establishment movement. These factors combined further hinder any across-the-board realignment of American politics.

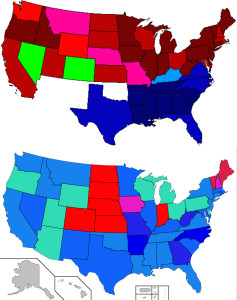

Building on the issue of polarization, at a time where the divide between blue and red states is so clearly defined, party realignment seems extremely improbable in today’s political climate. Realignment entails a dramatic change in the political system, usually caused by a major historic event. Three criteria have been used to characterize political realignment: a critical presidential election in which the electorate changes its voting pattern; a major conflict that divides the electorate; and a political party weak enough for a new party to either take control or to reflect a significant change in voter characteristics.7

Using this definition and these criteria, the history of realignments in the U.S. shows a very different situation leading up to previous realignments from today’s political atmosphere. The transition into the fourth party system, for example, was catalyzed by the Great Depression and Roosevelt’s New Deal, realigning political attitudes and different group’s party preferences based on whether they benefited from the Democratic president’s sweeping policies. Some posit that the 1960s Civil Rights movement also ushered in a new realignment. Whether the movement in the 60s has ushered in a new party system is a contentious debate in itself.

As compared to the profound social and political changes exhibited in the 1930s and 60s, how can analysts consider Trump and Cruz’s radical ideas within the Republican party necessary and essential catalysts for such a profound change in the American party system? To compare these drastic shifts in political attitudes, groups’ party identifications, and social factors of these historical cases of changes in party system to today’s chaos in the GOP is to compare apples and oranges. The current disagreement in the GOP is relatively insignificant vis-à-vis the profound changes that occurred in the 1932 election or during the Civil Rights movement.

In addition, for a new political realignment to occur today, political compromise and cross-aisle voter movement would be required. And as we’ve seen, compromise in American politics seems increasingly unlikely. The nature of the antiestablishmentarianism Trump and Cruz are promoting makes it improbable to bring about long-lasting party realignment.

Another factor that makes realignment unlikely is the fact that antiestablishmentarian sentiment is not confined to a certain region, race, or religion. Instead, it permeates many different sociological groups in current American political culture. Thus, there is a low possibility of certain states, based on their stance on establishment politics, switching colors or sparking creation of new parties. Unlike the New Deal when African Americans unitedly migrated from the Republican party —which they had supported since the Civil War— to the Democratic party, there is no clear shift along current sociological divides. Thus, the criterion for a political alignment which requires changing of voting behavior and patterns within the country is not upheld.

Conclusion

Fret not. The current American polarization of politics and discontentment in Washington will not actually bring about new parties or radically different party bases anytime soon, at least not due to the current anti-establishment movement. Nevertheless, there is still the monstrous threat of ideological and policy divergence in the American political landscape. This plague of gridlock and stunted political discussion cannot be ignored. Thus, instead of debating future party systems and political alignment, political analysts and pundits must get to work on better understanding the causes and solutions to the increasingly polarized American political landscape. That way, we Americans can finally get back to work on accomplishing what our Founding Fathers knew we were best at: compromising and getting things done.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

1 http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/06/12/polarized-politics-in-congress-began-in-the-1970s-and-has-been-getting-worse-ever-since/

2 http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/10/us/politics/for-republicans-mounting-fears-of-lasting-split.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=first-column-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news&_r=0

3 http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/01/12/presidential-job-approval-ratings-from-ike-to-obama/

4 http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/06/12/7-things-to-know-about-polarization-in-america/

5 http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/06/12/7-things-to-know-about-polarization-in-america/

6 (http://www.pewresearch.org/files/2014/06/FT_14.06.13_congressionalPolarization.png)

7 http://inhomelandsecurity.com/commentary-the-sixth-political-party-realignment-and-the-end-of-the-gop