Are Europe’s Niche Parties Serious?

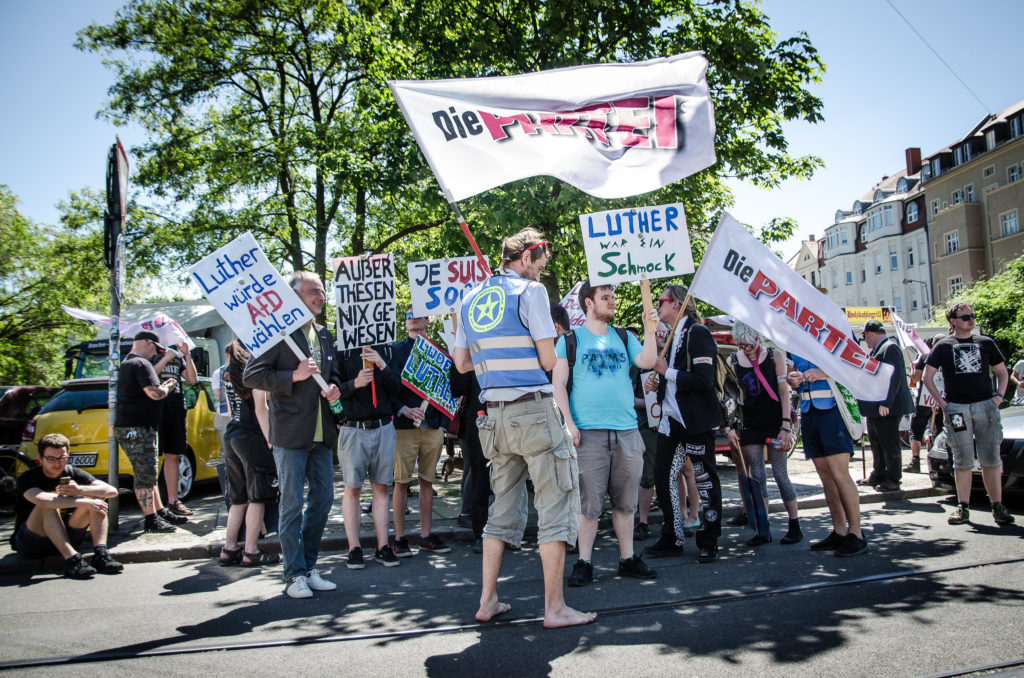

Germany's satirical Die Partei gained seats in the recent European Parliament elections.

https://flic.kr/p/UXH5v7

Germany's satirical Die Partei gained seats in the recent European Parliament elections.

https://flic.kr/p/UXH5v7

The incoming class of European Parliament (EP) members promises to be a politically diverse one, with the ascent of political groups other than the two who usually dominate, social democratic S&D and Christian democratic EPP. While broadly speaking, Green parties and Euroskeptic right-wing parties gained seats, so did eclectic, small parties. This isn’t new; European Parliament elections usually suffer from low turnout, bottoming out at 43% in 2009, relatively low compared to national elections in which upwards of 50% often turn out. In such circumstances, devoted activists and purists partake in disproportionate numbers, leading to the election of small parties, especially where many EP seats mean that the threshold for entry is very low, as in Germany and France.

Historically, some of these parties have been personalistic, some extremist, some strange, and many, a combination of the three. They often reflect niche issues. In France’s 1999 EP election, a party called Hunting, Fishing, Nature, Traditions garnered 6.78% of the vote and won 6 seats, even winning the Department of Somme. In Spain in 2014, Union, Progress, and Democracy (UPyD) won 4 seats after winning 1 in 2011 on a platform based around rejection of Basque and Catalan nationalism. While neither of these oddities is represented in the new EP, more than a few interesting smaller parties found their way to Brussels.

These small parties often reflect a malaise, fed by the perceived failures of established politicians in confronting complex issues like globalization. Populist movements on the right or left that blame foreigners or financiers tend to capture this malaise. In some contexts though, disillusionment manifests itself in a “burn it all down” mentality seen especially (but far from exclusively) in satirical and pirate parties. Often excluded from discussions on populism, due to their smaller role, these anti-system parties are united by a desire to revolutionize government itself, instead of solely replacing incumbent leaders. Scholars also note that anti-system parties eschew cooperation with other political entities, perhaps because of the rejection of the political mainstream. This culminates in an alternative vision to extant offerings, especially through new forms of connection with a voting base. This base tends to be young and disillusioned, ripe for political protest. It’s worth asking whether these small, seemingly niche anti-system parties can play a serious role in governing. Emerging from the 2019 EP elections, Germany’s satirical Die Partei and the German and Czech Pirate parties help answer this question.

Satirical Parties Not Serious Parties

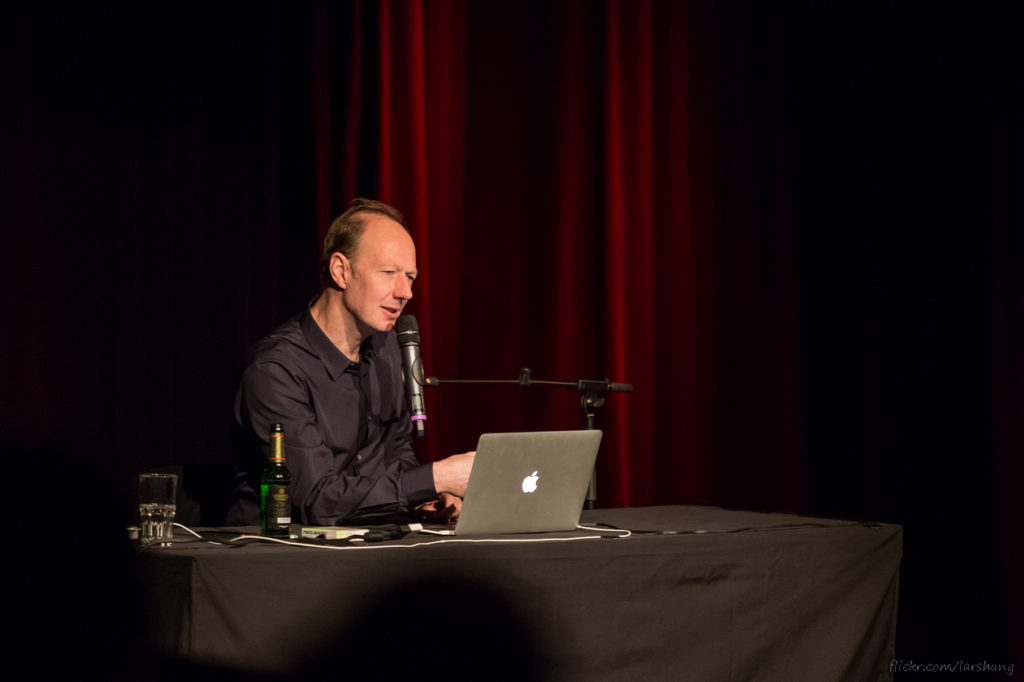

As one type of anti-systemic entity, satirical parties capitalize on the discontent voters feel with politics; these parties include Germany’s Die Partei and Hungary’s Two-Tailed Dog Party. Their platforms enrich an often serious discipline with humour. While in most countries, Hungary included, joke parties fall short of the threshold to enter the EP, in Germany, Die Partei obtained one seat in the 2014 EP elections and gained a seat in 2019 to bring their total to two seats and 2.4% of the vote. Die Partei was founded in 2004 by satirical magazine editors, using a strong online presence as a launching point for elections, despite a relatively low paid membership of 25,000. Partei’s name not only means party, but humorously stands for “Work, Rule of Law, Animal Protection, Elite Promotion, and grass-roots democratic Initiative”, parodying frequently used political buzzwords. Rather unsurprisingly, Die Partei’s platform is a colourful mockery of what other parties promise, and their leader Martin Sonneborn is himself a comedian. Some of Die Partei’s most interesting ideas include invading Liechtenstein, promising to introduce prescription cocaine, and jokingly protesting against tourism in Berlin. To some, giving a joke party a platform might seem like a waste of space in Brussels and taxpayer dollars. In fact, this point seems fair upon mention of Die Partei’s silliest antics and ideas.

However, their humour is not limited to lambasting the system, allowing them to ostensibly undermine the German-far right. In this sense, maybe a satirical party can play a serious role. Die Partei developed a browser extension to block online mentions of far-right parties. In the EP, Sonneborn at times rose with bogus points simply to block neo-Nazi NPD member Udo Voigt from speaking. Sonneborn also cleverly spoke out against US torture of terror suspects with a question about whether Germany and the US would practice musical torture together. Another speech jokingly advocated expelling Ireland from the EU, not-so-subtly decrying their corporate taxation practices. Therefore, it’s worth asking whether a joke party can play a serious role in resisting right-wing populism and promoting a progressive agenda. Perhaps by targeting peoples’ frustrations with politics, these parties can make important points while capitalizing on anti-system resentment through humour.

That said, the nature of a joke party may undermine its ability to be a credible political actor. While Sonneborn and company claim to undermine the far-right, some of their stunts are offensive and tactless. For one, Die Partei’s party list for the 2019 EP election included a number of candidates with names eerily similar to historical Nazi figures, incensing observers from all political backgrounds. Additionally, in 2011, Sonneborn appeared in blackface on a billboard, using a racist trope against then-US President Barack Obama. Die Partei’s willingness to employ prejudice contradicts their ability to combat the far right — after all, why rely on the far right’s offensive symbolism for supposed humour? As long as Die Partei focuses on edgy, offensive ‘humour’, they detract from their own ability to affect positive change. Thus, while humorous parties can promote progress, this positive role can be quickly overshadowed by an inclination to shock the public.

Pirate Parties As an Example of a Movement Getting Serious

However, another group shows how a small youth-driven anti-establishment message can evolve into a more serious movement. Europe’s Pirate Parties reflect such an evolution. United in Brussels as the “European Pirate Party”, they will be represented by one German MEP, incumbent Julia Reda, and three members of the Czech Pirate Party, their highest-ever representation. While the name “Pirate Party” may hint at satirical leanings, these parties approach politics differently from those like Die Partei. Examining the origins of Pirate parties reveals much about their emphasis. Emerging in 2006 in Sweden and Germany, Pirate Parties primarily sought to change copyright laws to facilitate peer-to-peer file sharing and increase digital privacy. Despite this focus, their initial attempts seemed amateurish. For example, German Pirates first organized on a wiki page run by a man who referred to himself in a fictional language.

This initially seems like an overly narrow focus and a disorganized strategy, but the success of Pirate Parties emerges from what they’ve come to symbolize — a broader youth-driven, technocratic protest movement. While the German Pirate Party entered a period of domestic decline after initial success, observers like the American New Republic magazine note that they tapped into an understanding of “how state intervention in the internet has impinged on civil liberties”. Others point to increasing governmental regulation and surveillance of technology causing anxiety among internet users. Electoral results flesh out this explanation. A study by political scientist Simon Otjes reveals that factors leading people to vote for Pirate Parties include youth, distrust of traditional politics, and concern about cyberlibertarian issues like privacy. This reveals a growing seriousness, guided by political disaffection, behind what might have seemed like an ephemeral movement.

An examination of their platform, shared by organized Pirate Parties, demonstrates incorporation of concerns beyond technology. Initially, the Pirates’ platform was confined to reforming copyright laws, ending patents, and respecting privacy. Nowadays, their shared platform includes issues ranging from supporting sustainable local agriculture to arms trade treaty implementation to the legalization of marijuana. That said, despite a diverse left-libertarian focus, a significant portion of the platform remains devoted to privacy, copyright reform, and the ‘traditional’ issues of the Pirate Party. Such proposals include rejection of increased government surveillance, the ending of patents for software, and legalizing copying music for non-commercial purposes. While ideas like abolishing patents are borderline untenable, the existence of a unifying platform for Pirate Parties allows them to reach past their initially narrow focus and become established as a serious political movement, particularly because technology impacts many issues.

Moreover, Pirates have a record of legislative action in Brussels. Recently, German Pirate Party MEP Julia Reda worked with NGOs to organize protests in 45 cities against a highly restrictive drafted copyright reform law in the EU. The bill, specifically Article 17, would lead to internet media platforms assuming responsibility for copyright violations, possibly causing a crackdown on videos, memes, GIFs, and other forms of online communication. While the law unfortunately passed anyway, Reda successfully advocated changes to the legislation and effectively tapped into public discontent. Especially as governments, including the EU, confront a rapidly changing technological landscape, niche technocratic parties help protect internet users and voice their concerns.

The Pirates’ electoral success also warrants a more serious outlook. The Czech Pirate Party has been especially successful lately. In the 2017 national elections, the Czech Pirates capitalized off political deadlock and widespread perceived corruption — two ingredients that fuel anger at the government establishment. This cements them as an anti-system party. Winning 22 seats in Parliament in 2017, the Czech Pirates became the third largest party. Moreover, in the 2018 municipal elections, they captured the mayorship of Prague, and currently, they’re polling 19% nationally, sufficient for second place. This success, reflected again in EP results, demonstrates that while remaining true to their anti-systemic roots, Pirates can grow their base through the aforementioned channels of support. What seemed like a small online movement is quickly becoming a vehicle for political protest from younger generations. The Czech Pirates also propose a broad platform that encapsulates these concerns. For example, they seek more equitable taxation structures and eventually a universal basic income. These ideas appeal not only to fringe voters, like some populist proposals do, but to centrist voters whose anger with the government doesn’t cloud their pragmatism. Similarly to satirical parties, Pirate parties employ an anti-establishment viewpoint. But, instead of mocking the system’s shortcomings, they propose a decidedly more serious alternative to ‘politics as usual’, evidenced by their ability to win more seats than satirical parties and propose diverse policies.

Conclusion

As exemplified with by two movements, lesser-known anti-systemic parties can serve as agents of political change, although those who wish to be taken seriously must branch out and renounce boundary-crossing immature attempts at humour. Nonetheless, the dichotomy might prove tough to sustain. The distance between satirical and serious anti-systemic parties often proves more blurred than the dichotomy between Die Partei and the Pirate parties would suggest. Satirical parties can change over time, seeking political incorporation. After all, the Movimento Cinco Stelle (MS5) party in Italy, now a part of the governing right-wing coalition with Lega, began as an anti-establishment party started by Beppe Grillo, a provocative comedian, on his rant-filled blog. Its first slogan and logo comically employed profanity against political incumbents. Over time, its unhinged, almost-mocking rhetoric ascended to a prominent place in the Italian government, showing the potential for evolution of satirical anti-system parties. However, if straightforwardly satirical groups like Die Partei give up their act, they may have to contend with internal division. It’s worth remembering the downfall of the Polish Beer Drinkers’ Party, which won 16 seats in the Sejm (Parliamentary) elections of 1991 but split into two over whether or not to continue being humorous. Thus, while Die Partei’s antics might elicit chuckles in Brussels, the rise of small niche parties isn’t just a laughing matter.