Automation and the Death of Self-Sufficiency

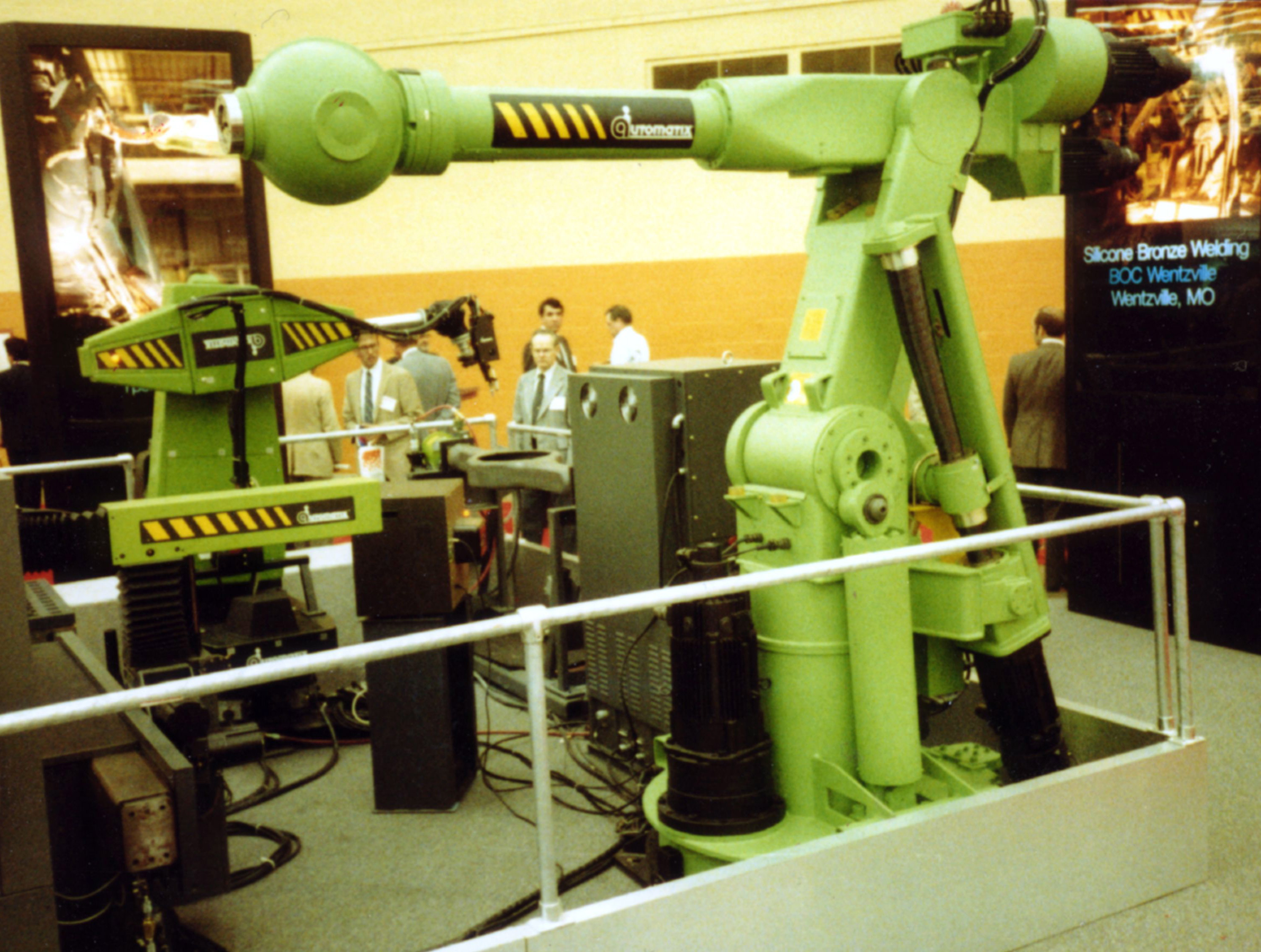

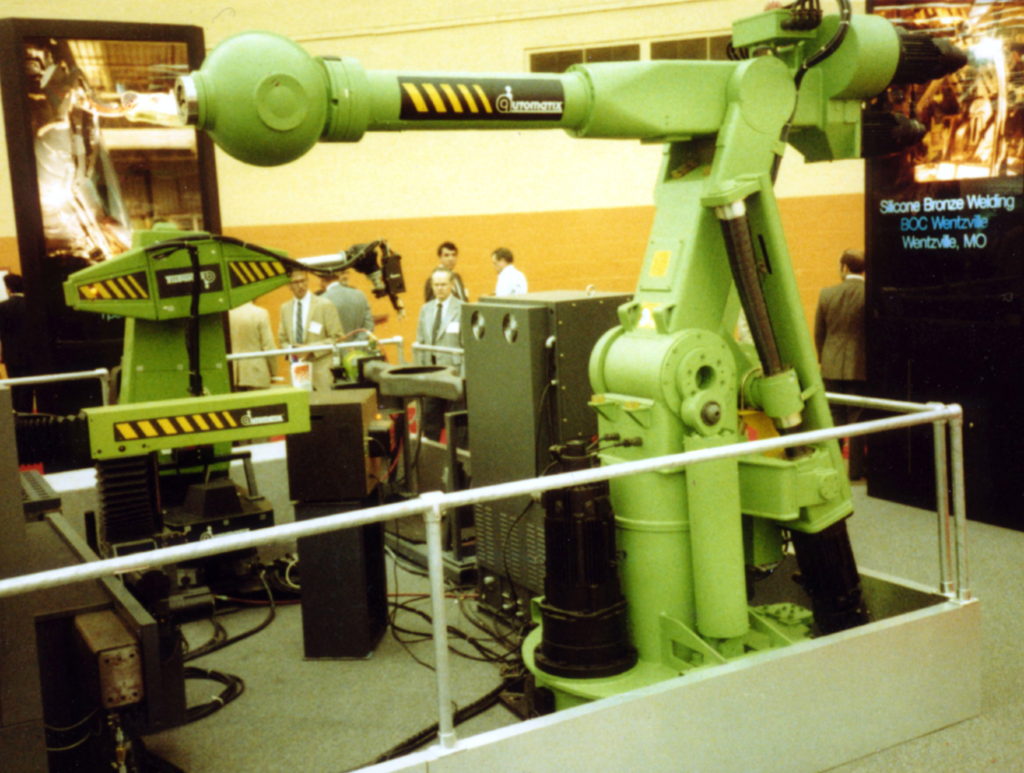

Robots and machinery are a critical part of modern industry

Robots and machinery are a critical part of modern industry

It was long considered a “stylized fact” of economics that the division of income between labour and capital was a set ratio. Charles Cobb defined it as the owners of capital receiving a third of national income, and labourers the other two thirds. This “miracle,” as John Maynard Keynes referred to it, is the result of the fundamental economic desire to minimize costs and is an important factor in maintaining income equality and fair wages. If this ratio falls too far towards the capital side, less and less of the wealth produced by the economy goes to workers. Instead, owners of capital will benefit.

Automation promises to disrupt this careful balance. What happens when there are few jobs left in the economy that can’t be done better, for cheaper, by a robot?

The “Miracle” of Income Distribution

“National Income” can be divided into capital and labour shares of income. The miracle of steady distribution results from the economic desire to keep costs down, and profits up. The higher the demand for capital–in sectors such as heavy industry–the higher the cost of production. Higher cost of capital incentivizes hiring more labour instead, leading to the careful balance we saw for nearly a century.

This is no longer the case. As capital becomes simultaneously cheaper and more efficient, companies are incentivised to invest more in capital production, and less in their labour force. From 1950 to 2001, the labour share never deviated far from 62%. In the 13 years after 2001, it fell to 56% of income: a significant drop for one of the static figures in economics.

Keynes’ “miracle” is already dying, and we’ve only seen the tip of the iceberg in terms of capital efficiency.

The Big Shift of Automation

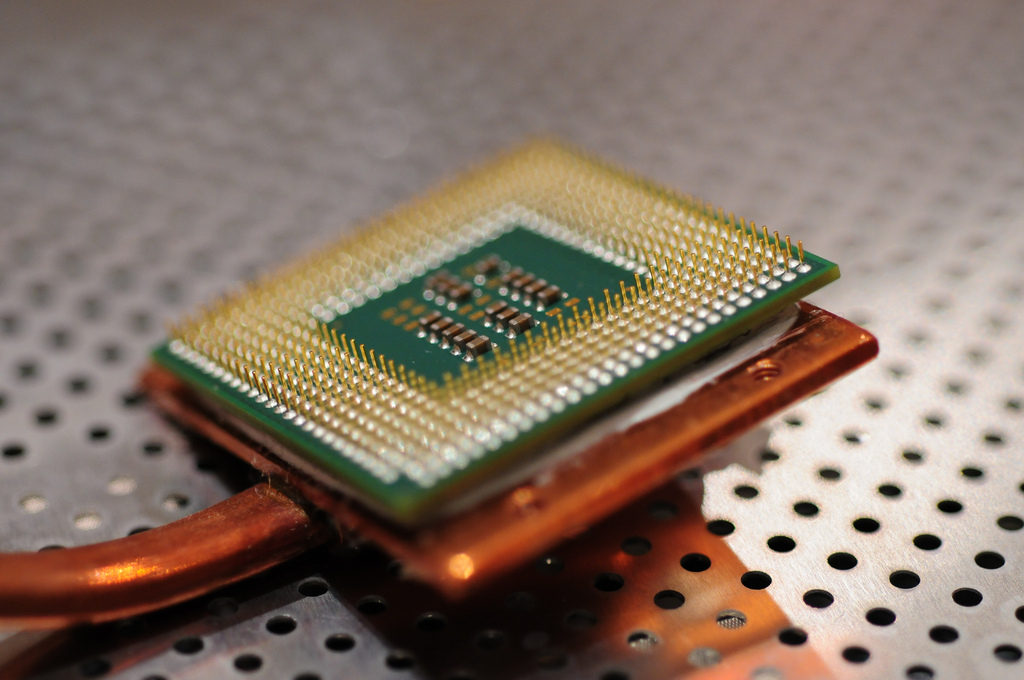

Automation is a term that almost feels like a buzzword. It has been discussed for decades as computers have grown more powerful and software has grown more sophisticated. Nonetheless, automation has yet to radically disrupt the fabric of our economy. It is, in fact, still in its infancy.

However, this is poised to change. At present, more than 40% of the Canadian workforce is at “high risk” of being replaced by automation within the next 20 years. In 2011, there were 283,185 Canadians employed driving trucks. If self-driving vehicles continue to hurtle towards market viability, then it is easy to see that 283,000 people may be out of a job in the near future, in addition to others whose professions revolve around driving a vehicle. Due to point of sale advances, grocery clerks are being phased out. Advances in automated machinery have reductions in the number of people necessary to build cars. These are just two of a thousand examples of how automation is changing our workforce. Human labourers are still necessary for the majority of jobs, but consider what might happen if heavy machines become self-driving or if a digging robot appears on construction and engineering sites. The changes would be huge.

Structural unemployment–unemployment that is a result of shifts in the economy–is not a new phenomenon. New technologies or market conditions continually change which occupations are in demand. This leads to unemployment as people lose their jobs in obsolete sectors.

The key difference here is the scale. Automation in the past has been a relatively slow process as our computers and machines advanced. Today’s level of automation promises to revolutionize the way we work, as computers and machines advance exponentially and become better suited to take over jobs that previously needed a human’s touch. Soon, there may not be many jobs that a machine can’t do better.

Income in an automated world

Elon Musk, the CEO of Tesla and SpaceX, has said that “Robots will be able to do everything better than us”. The pace of development in artificial intelligence is remarkable. In 2016, a division of Google’s Deep Mind beat the reigning World Champion at the game of Go, 4 to 1. Go is a board game famous for its complexity despite its simple rules. Experts said this win was a decade ahead of its time.

If automation continues to rapidly grow, and there is no reason to believe it will slow, there will be a serious need to re-evaluate how wealth is distributed. Capital will continue to draw larger and larger shares of income as it replaces many positions previously held by workers, because automation promises to expand the usefulness of capital investment. No need to hire a salesperson if an automated checkout machine will do it wage free. If 40% of Canadian jobs are indeed at risk in the next two decades, and certainly more in the years after, there will be significant human suffering as incomes decline and people lose their jobs. More importantly, we may begin to enter a world where there simply are not many jobs that are done by people; most jobs will be handled by machines. And the real winners of an increase in capital income are the owners of capital – the wealthiest members of society.

Universal Basic Income

Universal basic income (UBI) is a concept that has been gaining traction in recent years. It’s a simple one at its core: replace the complicated, administratively expensive social safety net with an unconditional, liveable wage received independently from other sources of income. UBI is the ultimate safety net, as it ensures that everyone is able to provide for themselves no matter the economic conditions they find themselves in.

This may seem like a utopian idea, but lawmakers are already experimenting with it. Ontario has begun enrolling participants in a limited UBI experiment, with the stated goal of finding out “whether a basic income can better support vulnerable workers, improve health and education outcomes for people on low incomes, and help ensure that everyone shares in Ontario’s economic growth.”

A UBI would help reduce concerns that automation would hurt income equality and vulnerable workers. If the more than 280,000 truck drivers in Canada find themselves replaced by self-driving trucks, even those who may be too old to be able to find productive new employment would still receive a livable wage. Structural unemployment, resulting from shifts in the economy, would hurt people less because they would have a guaranteed income.

That’s not to say we are ready for a UBI yet. People are still the driving force behind every product and service the modern economy provides. But if automation continues at its breakneck pace, soon machines will be doing most of our jobs. The best social good comes when we use this potential to help all of us – not just those of us fortunate enough to own the new automated capital that will run our economy.