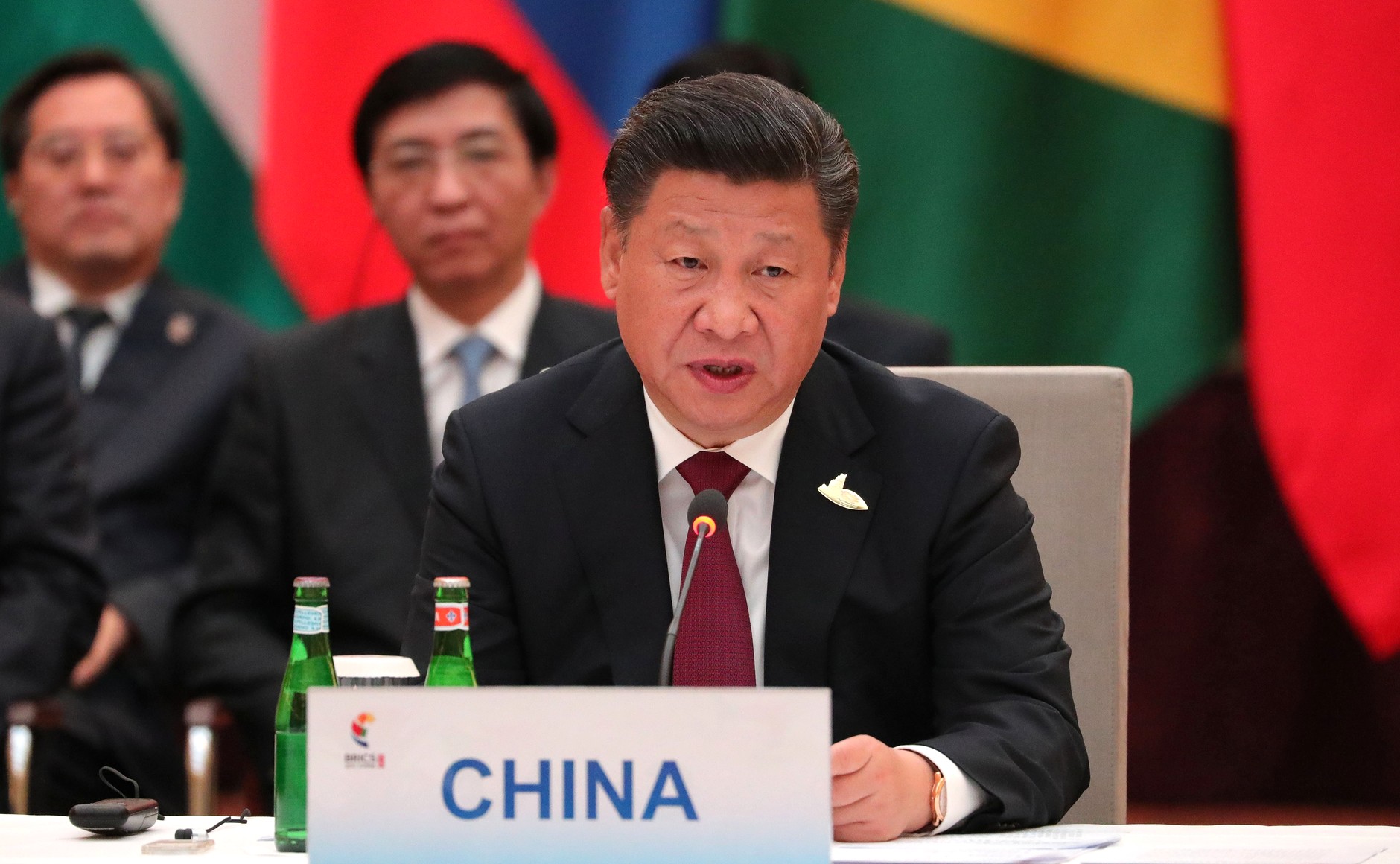

Awaiting “Never again”: The Persecution of Uyghur Muslims

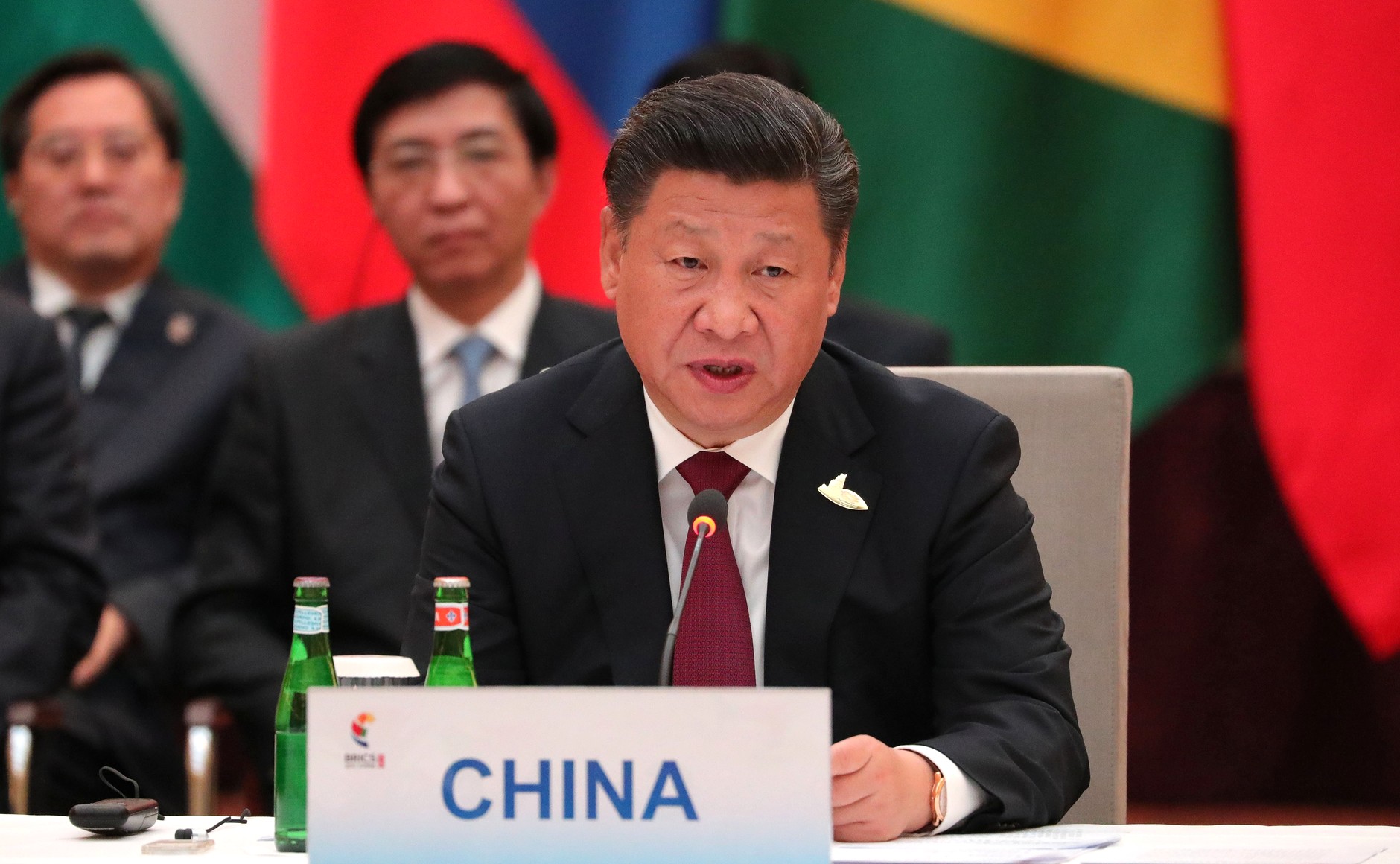

President of China, Xi Jinping has XinJiang province under intense military surveillance

https://bit.ly/2NSYC34

President of China, Xi Jinping has XinJiang province under intense military surveillance

https://bit.ly/2NSYC34

Spanning over 9.5 million square kilometers, encompassing over 1.3 billion people and a rich history, China is far from a homogeneous society, in both people and land. However, under President Xi Jinping’s rule, China has made its beliefs clear: a homogeneous society is all that will be tolerated. Human rights abuses is not alien to Chinese history and has long been reflected in the treatment of religious minorities in the provinces of Tibet and Xinjiang. Most recently, the persecution and oppression of the Uyghur population, who are predominantly Muslim and largely based in the Xinjiang province of China, has become increasingly apparent and alarming to international media.

https://bit.ly/2OtRyqI

In China, the government recognizes around 55 ethnicities; however, the Han Chinese majority has a strong presence in nearly all regions. The notable exceptions are Tibet and Xinjiang, leaving no coincidence as to why the Chinese government runs a tight ship in these provinces. The Uyghur Muslims are considered an ethno-religious group of Turkic descent. While found in large numbers throughout central Asia, the majority are by far concentrated in China. From their practice of Islam, as opposed to the non-religious majority of China, to their unique language and cultural practices – the Uyghur are seen as distinct from the predominant Han Chinese ethnicity in China. The incorporation of the Xinjiang province within China is relatively new, only occurring in the 19th century under Qing rule. However, intensified hostility towards the Uyghurs can be traced back to the mid-20th century. To assert control, Beijing launched aggressive settlement policies which relocated many Han Chinese to the province of XinJiang. The resulting rapid growth of Han Chinese in the area fueled animosity between the ethnic groups as tensions began to quickly escalate.

In attempts to garner support to escape from the oppressive rule, there have been separatist groups and movements in the Xinjiang region. Consequently, Beijing has exploited these groups by labeling any dissidence as terrorist-separatist agenda. Despite its troubled history, the worst was only yet to come for the Uyghurs. The 9/11 attacks created a platform for China to suffocate the livelihood of the Uyghurs, marking a shift in governmental policies and monitoring of the Xinjiang region. Any act of rebellion or deviance by the Uyghurs became labelled as terrorism. This increased surveillance has only intensified under President Xi Jinping’s rule; being likened to a modern-day police state.

https://bit.ly/2NSYC34

According to the government, simple acts of worship, such as having a long beard, covering up, or really any representation of Islam became acts of “terror” and “rebellion”. These policies and sentiments have now culminated into what many have called “political re-education” camps but are nothing less than internment camps. As China has denied any existence of such camps, specific figures have been difficult to pinpoint; however, some reports have estimated a figure of up to 1 million people being detained. Treatment of captives include force-feeding pork and alcohol consumption, as these are prohibited in Islam, only exacerbated by the psychological warfare of stripping them of their ideological beliefs. Furthermore, reports of torture, and possibly even death, have surfaced. It is said the government is viewing Islam as a pathology; akin to a mental illness that can be eliminated from its society.

Is China anti-Islam?

Utilizing Islam as a a proxy for policy targeting is evident in the the detention and “re-education” of the Uyghurs, as well as Kazakhs of the region; however the issue remains more complex than that. The contentiousness lies in China’s adoption of what is “Chinese” and what is not. Simply put, China does not see the Uyghurs (or Kazakhs, and Tibetans) as Chinese, or at the very least, not Chinese enough. Not only does China employ differences in language and religion as discriminatory agents, but also as means of exerting control. The purpose of the internment camps is to quell any noticeable “differences” between Uyghurs and the Han Chinese. This way, in the view of the Chinese government, a homogenous society can be achieved.

The hypocrisy is blatant as China, and specifically Xinjiang, has a sizeable Hui population minority, who also predominantly practice Islam. Unlike the Uyghur population; however, the Hui Chinese are considered to be of Han descent. The Hui people have had an amicable relationship with the state, fully allowed to exercise their religious freedom and practices. The Hui are visibly more integrated within China; scattered around many of the largest Chinese cities. It is clear that the Chinese government views the Hui people as they are: Chinese. They are not seen as a threat, they are seen as loyal to the state. Yet despite practicing the same religion, or at least forms of it, these two groups face distinctly different realities. For example, Hui Muslims are allowed to fast for the Islamic holy month of Ramadan, whereas Uyghur Muslims are strictly forbidden from doing so. This has fostered animosity between the Hui and Uyghurs, two groups who share a religion, further feeding into the narrative that the Uyghurs are distinct from being Chinese.

Hello world? Are you out there?

The longstanding abuse of the Uyghur under Xinping’s rule, escalated as reports of the internment camps, surfaced in early 2017. However, only in March 2018 did we see the first mention of these internment camps by the UN at the Human Rights Council; international news outlets began reporting on the matter more extensively in the summer of 2018. In September of 2018, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination released a statement merely offering recommendations China should take to improve its human rights track record. When this is the most a specialized UN body can do; the voice of the international community becomes crucial, especially in the face of an economic superpower such as China. The United States has recently voiced its concern but there has been no formal call to action, no sanctions, and not really any strong language to indicate that any Western powers are doing more than raising an eyebrow on the matter.

Turning to Muslim-majority countries, we get silence. While not all Muslim-majority countries are beacons for human rights themselves, they have in the past at least spoken up on some issues to demonstrate some kind of solidarity with its fellow Muslims. The Organization of Islamic Cooperation and Muslim nations such as Indonesia have raised their voice against Myanmar (for its persecution of Rohingya Muslims). However, taking the parallel of Rohingya Muslim persecution in Myanmar, the Rohingya crisis had escalated to being classified as a genocide before the world took note. Will it take similar levels of atrocity in China for the international community to do something, anything?

As the economic powerhouse that it is, China remains with the upper hand in this situation as it is dubious whether any country will stand up to the prowess of China. The stakes are simply too high, for Muslim and Western countries alike. China has already come out defending its policies and telling other countries to not meddle in places where it ought not to. However, the United Nations General Assembly debates began on September 23rd; and being a more visible platform for countries to voice any disapproval of current international events, it is a major opportunity to present a global united front.

https://bit.ly/2OvPXkb

The world has an uncanny way of deeming who is worthy of helping and who isn’t. So the question remains whether yet again the world will idly await until another targeted genocide occurs to say “never again?”

Edited by Shaista Asmi