Balochistan: The Overlooked Casualty of South Asian Soft Power Relations

As Asian nations grow in power and economic clout, regional disputes have increased, most publicly through conflicts in the South China Sea and Kashmir. India’s conflict with Pakistan along its North-Western border is arguably the most publicized dispute between two nuclear powers since the end of the Cold War. The spillover from their struggle has resulted in a new, but less publicized front between the two in Balochistan, as India attempts to subvert a threateningly invigorated Chinese-Pakistani alliance in South Asia.

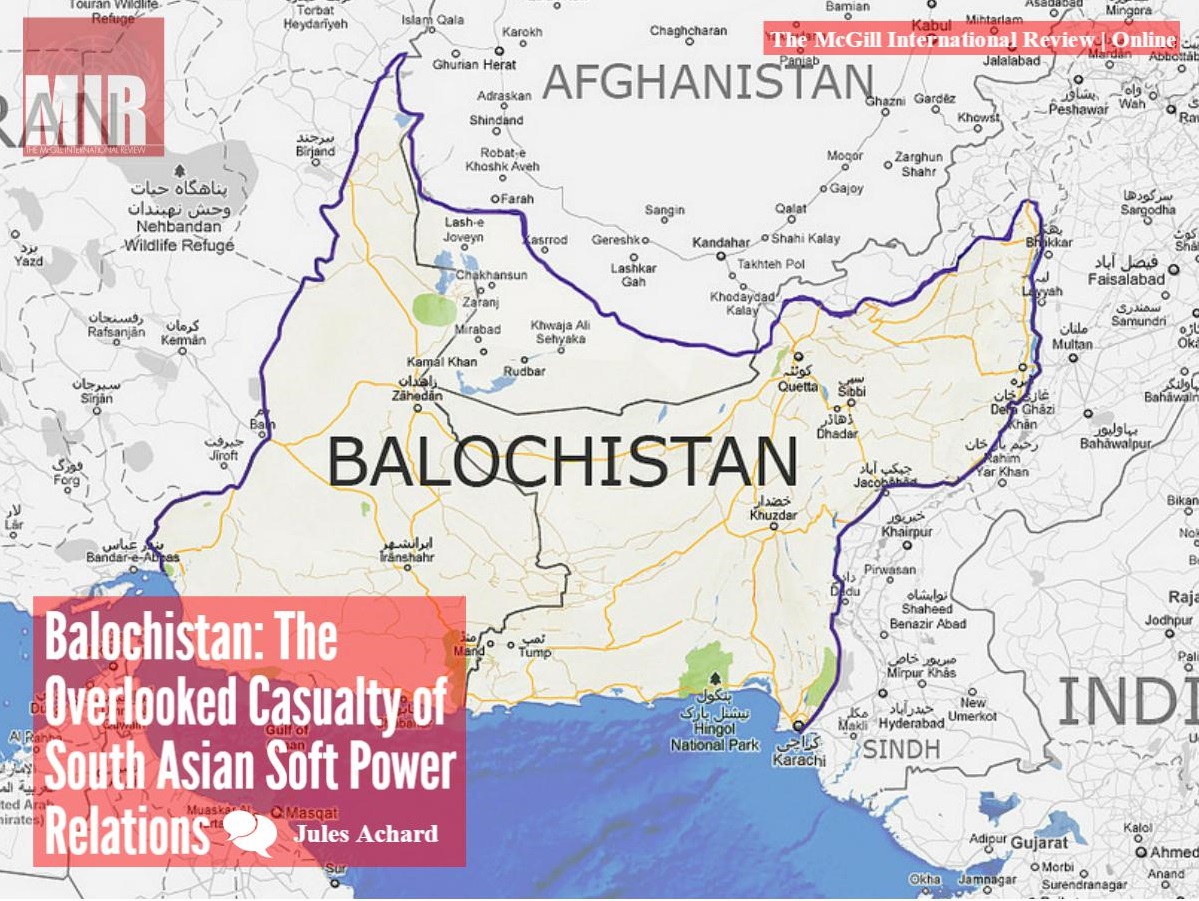

With its strategic geographic location split between Pakistan and Iran, large natural endowment sitting beneath a scarce and underdeveloped population, Balochistan is similar to Tibet or Kurdistan; its indigenous population repressed for the benefit of a larger power’s interests. Despite much less international media coverage of the atrocities and conflicts taking place in the region by comparison, the consequences of China’s interest and investment, particularly in Gwadar, a deep sea port near the Arabian peninsula, will surely have put the West on notice. Balochis can lament their unfortunate geographic location at the center of one of the world’s new economic crossroads, including them in global power dynamics between regional and supra-regional powers that will ultimately and arguably provide them little or no benefit while forcing Pakistan to tighten its control over the region.

The largest of the four provinces of Pakistan, Balochistan holds only seven percent of Pakistan’s population, only half of whom are native Baloch. Balochi nationalists have accused the Pakistani government of attempting to make them a minority in their own province in order to neutralize any power that vocal and increasingly violent nationalists have. The poorest region of Pakistan, it has long been underdeveloped, with the lowest overall literacy rates, including a mere 19 percent of women. This is despite sitting above vast and varied natural resources, including gold, oil, copper, coal and natural gas. Balochistan’s location by the entrance to the Straits of Hormuz, one of the worlds most important shipping root makes it essential to Pakistan, and now to China.

Beijing has sought to take advantage of Balochistan’s strategic geographic position as it faces off increased regional activity by India. President Xi Jinxing has poured 46 billion dollars into Balochistan under a 2015 agreement with Pakistan creating the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). The ultimate goal of retaining access to the Arabian Sea, and the shortest route to the petroleum rich Middle East, would officially make China a two sea power, with important economic and military implications for South Asia.

Despite both the Chinese and the Pakistanis denying that Gwadar Port would be used for anything but economic purposes, the Indians and the Americans are wary that this could provide the Chinese Navy with a port to the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. On top of that, the proposed route to Gwadar passes through Pakistani controlled Kashmir, which the Indians claim as their own and has been at the center of escalating tensions and activity this year.

The timing of such an announcement can be easily linked to the six month Iranian-Indian treaty which sees India gain access to the Iranian port of Chabahar through a 20 Billion dollar investment. This will give India, which is allied with the US, significant economic clout in the region through its location on the Gulf of Oman. The goals of the treaty are extremely transparent, with Iran-Newspaper claiming that, “India wants to challenge China’s power in Central and South Asia through Chabahar port.”

The treaty finally gives the majority Hindu nation the foothold in Central Asia that it has worked for since it was separated from the region by Pakistani independence in 1947. Ex-Indian Foreign Minister Maharaja Krishna Rasgotra says that the agreement will work to convince Pakistan, “that it cannot continue to play the role of an obstacle for India’s plans for Central Asia.”

Nonetheless, Chinese access to Gwadar will give both China and Pakistan an answer to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s more recent aggressive stances in his attempt to turn India into a regional powerhouse. Despite the soft power dynamics at play, open war is certainly not in the cards; both China and India require peace in destabilized Central Asia in order to gain prestige and economic clout through these nascent trade deals.

Accordingly, Pakistan has attempted to comply with Chinese needs, deploying 10,000 soldiers to secure the project, while repressing dissent and any and all independence movements in Balochistan. While the Pakistanis claim that the corridor will transform and develop an impoverished region, Human Rights Watch has documented numerous instances of torture, extrajudicial killings and coercion by the Pakistani military in its attempts to ensure dominance over the region. The Balochistan home department claims nearly 1,000 people have disappeared. Freedom of speech is at a low, as killings and disappearances of journalists and human rights activists increases. Most prominently, activist Sabeen Mahmud was shot dead in April, 2015, not long after hosting an event on Balochistan’s disappeared people in Karachi.

Human rights violations have been documented on the side of the Balochis as well, where militant guerrilla groups have increased attacks on non-native citizens. While these are inexcusable transgressions against laborers removed from the sphere of government manipulation, this can only be characterized as stemming and resulting from the government repression and diminishing influence of Balochis within their own borders. As law and order declines amid a disintegrating civil society, Pakistan’s military class have escalated repression and allegedly filled the region with non-Balochis in order to decrease the political power and influence of their ethnicity, a reflection of the strategy used by the Chinese in the Tibet Autonomous Region.

The most prominent militant dissenters are the Balochistan Liberation Army, who have been fighting for secession or greater regional autonomy since 2000. Listed as a terrorist group by both Pakistan and Britain, they claim grievances over the allocation of jobs to Punjabis over Balochis and the government monopoly over natural resources, among other tribulations. Their movement was further sparked in 2005 after the rape of a female Balochi doctor by a Pakistani army officer, which encouraged many in the region to leave behind ancient tribal differences that had been exploited by previous conquerers. Prime Minister Modi is accused of aiding the group and has taken an increasingly determined stance towards Pakistani human rights transgressions in the region in order to undermine his regional adversary.

As power plays and regional stakes increase, it is very clear that Balochistan is not the first to suffer the butt end of a regional power play in which it is not involved. Nonetheless, it will require increased international supervision as China and Pakistan attempt to quietly tidy up an overtly agitated region in order to complete the corridor’s vast and costly infrastructure. As China pursues its hegemonic and imperialistic ambitions, Balochistan is caught in a Sino-Indo-Pakistani love triangle that is beginning to rear its ugly head.