Beijing Looks South: Geopolitics in the South China Sea

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fig_2_Bathymetry_map_of_South_China_Sea_Basin.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Fig_2_Bathymetry_map_of_South_China_Sea_Basin.jpg

The acquisition of territory has historically played a prominent role in the history of geopolitics and has been a benchmark for a state asserting its power. While the territorial conquests of the past no longer serve as legitimate means of expanding a state’s sphere of influence, China’s expansion into the South China Sea seems to be their maritime loophole to this political norm.

The History of Sino-Philippine Tensions in the South China Sea

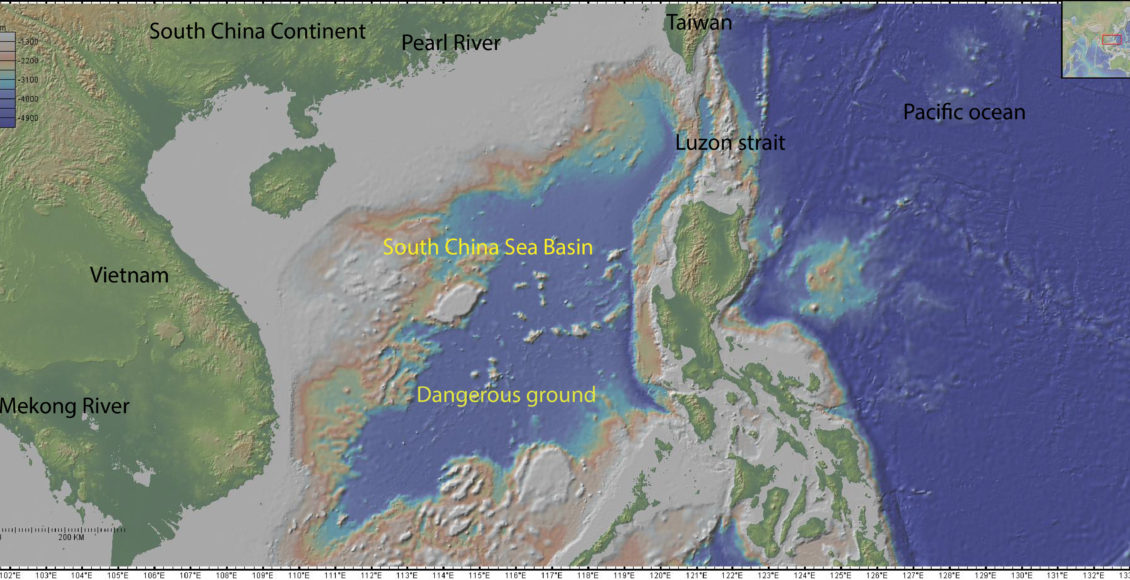

The South China Sea is one of the busiest shipping and trading routes in the world with an abundance of natural resources beneath its seabeds. The Chinese government has proclaimed the entire sea to be theirs based on a number of historical claims. Ancient Chinese dynasties had fished and traded in the sea, deeming it as the “Silk Road of the Sea.” The sea was first used by the Qin and Han dynasties from 221 BC – 220 AD and prospered under the Tang and Song dynasties from 618 – 1279 AD. However, the prosperity of the sea was only momentary, as the Ming and Qing emperors successors banned all maritime trade from 1474 – 1551 due to piracy, and the entire route was abandoned in 1840 following the Opium War between China and Great Britain.

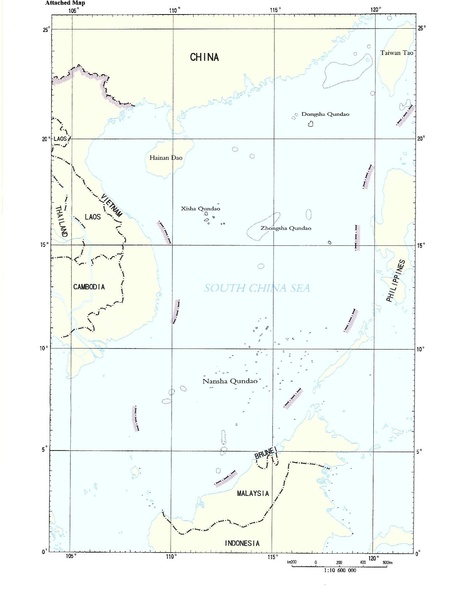

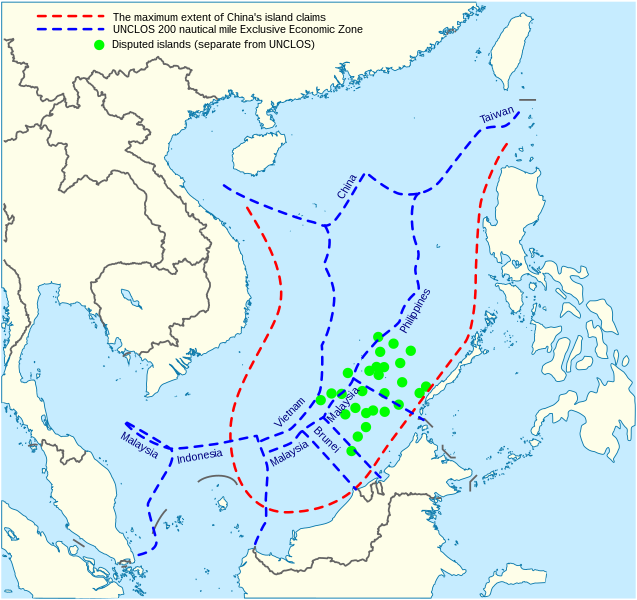

China’s current claim to the South China Sea is based on a Nine-Dash Line extending up to 2,000 km from the Chinese mainland and a few hundred kilometres from the coasts of the other nations involved in the dispute. First drawn up in 1947, the Nine-Dash Line was originally drawn as an Eleven-Dash Line by Chinese nationalists claiming that it encompassed “China’s maritime treasures.” However, two dashes were lost in 1952 when the Gulf of Tonkin was given to Vietnam and the territory claimed by China became the Nine-Dash Line. The current Nine-Dash Line comprises all the terra firma within the South China Sea and majority of its waters. However, uncertainty surrounds China’s claims, as it is not clear whether they encompass all the water within the Nine-Dash Line or just the territories within it.

While there are many overlapping claims within the South China Sea, the main sources of tension between the Philippines and China revolve around the contested Scarborough Shoal, the Spratly Islands, and Reed Bank. Initially US territory following the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the Philippines was transferred ownership of the Scarborough Shoal following independence. In 2012, the shoal was the site of a tense confrontation between the Chinese and Philippine navies, which resulted in China gaining control of the shoal and preventing the entry of Filipino fishermen. Multiple nations have made claims over the Spratly Islands, which have been disputed since 1956. According to China’s claim, the islands were lost to the Japanese during the Second World War, but recuperated as a result of the Cairo Declaration and Potsdam Proclamation. The Philippines’ claim lay mainly within the Second Thomas Shoal, where the country has stationed a number of its forces. China has already built islands and airstrips within the archipelago, worrying its neighbouring states. Finally, the Reed Bank, about 100 nautical miles west of the Philippine island of Palawan, was once a site of oil exploration for the Philippines and an area where the Philippines maintains a claim of sovereignty.

On January 22, 2013, the Philippines began arbitration against China based on the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The UNCLOS, which all claimant nations have signed, has been the basis of international law for the South China Sea dispute. China rejected the arbitration and any ruling it may deliver, stating that “the two countries have overlapping jurisdictional claims over parts of the maritime area in the SCS and that both sides had agreed to settle the dispute through bilateral negotiations and friendly consultation.” Three years later, on July 12, 2016, the Hague Tribunal ruled that China’s claims to the South China Sea have no legal basis and that China had breached international law “by causing ‘irreparable harm’ to the marine environment, endangering Philippine ships and interfering with Philippine fishing and oil exploration.” As with all international law, the ruling relies on the consensual acceptance from all parties involved, but as they made clear in the beginnings of arbitration, China rejected the tribunal’s decision and maintained their claims to the South China Sea.

In the immediate aftermath of the ruling, uncertainty ran abound, with prominent fears that tensions could escalate. However, a year after the ruling, there were reasons to stay optimistic because Filipinos were finally permitted access to the Scarborough Shoal and Chinese rhetoric regarding the Nine-Dash Line wavered. Still, China continues, to assert its control in the region. According to the Pentagon, China has claimed over 3,000 acres in the South China Sea and has shifted its efforts “to developing and weaponizing man-made islands so it will have greater control over the maritime region without resorting to armed conflict.” As a result of China’s militarization of the region, the US retracted China’s invitation to the US-hosted multinational naval exercise conducted in the summer of 2018 and continued its freedom of navigation exercises. According to Professor Herman Kraft from the University of the Philippines’ Political Science Department, the US military’s freedom of navigation operations are the main obstacle of China’s ambitions and the primary enforcing mechanism of the tribunal’s decision.

History of The Philippines’ Policies

Historically aligned with the US, the Philippine government’s attitude and actions regarding the South China Sea dispute changed following the election of incumbent president Rodrigo Duterte. Under Duterte’s predecessor, Benigno Aquino III, the Philippines followed its traditional pro-American stance and adopted a stout stance in the South China Sea. The Aquino government did not back down from the Chinese expansion into the South China Sea, maintaining the Philippines’ claims in the region. In 2012, the Aquino administration renamed the South China Sea the West Philippine Sea and confronted the Chinese Navy in the Scarborough Shoal. Moreover, it was the Aquino administration who brought the Philippines’ grievances to the Hague and won the symbolic and principled victory for their claims in the South China Sea. However, while Aquino defended the Philippines’ claims in the dispute, the administration of his successor has accused the Aquino government of causing the militarization of the region when they dispatched the Philippine Navy to the Scarborough Shoal. Given the close proximity of the shoal, Chinese militarization of the islands creates an immediate security risk for the Philippines and could cause already tense relations in the region to deteriorate. Furthermore, Antonio Carpio, a Philippine Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice, asserts that the strategic value of the Scarborough Shoal, as the exit to the Pacific, makes Chinese militarization of the area appealing.

Duterte’s Policies

While the Philippines has historically been an American foothold in the Pacific, the election of Duterte drastically changed this narrative. Duterte has openly criticized the Philippines’ strongest military ally and increasingly leaned towards appeasing China, renouncing the Philippines’ historic pro-American stance in search of possible economic benefits. In November 2018, Duterte seemed to accept China’s custody of the South China Sea, stating that it is already under their possession and the military activities of states like the US unnecessarily create tensions and could provoke Chinese aggression. In the same month, Chinese president Xi Jinping visited Manila and left with an agreement between both countries to cooperate in the search for natural resources in the South China Sea. The agreement was met with protests in front of the Chinese embassy in Manila, illustrating the Filipino people’s frustrations regarding Filipino-Chinese relations. According to survey data, 84% of the Philippine population disapprove of the government’s inaction in the South China Sea following the Hague’s 2016 ruling. However, the Duterte administration holds pessimistic views on the arbitration, calling the ruling “useless,” while believing that “no power on earth” could pressure China into accepting the ruling. Still, analysts believe that while the ruling may not have much effect in its immediate aftermath, it serves as important leverage for future negotiations.

While Duterte has leaned heavily towards improving relations with China, the Philippines’ Foreign Affairs Secretary Alan Peter Cayetano outlined “red lines” in the South China Seas that the Philippines would go to war over: any construction on the Scarborough Shoal; any attempt to remove the BRP Sierra Madre, a Philippine Navy ship in the Second Thomas Shoal; any unilateral extraction of resources in the sea. China, for their part, declared a “red line” of their own, demanding that uninhabited territories in the sea remain that way. However, given Duterte’s anti-American rhetoric and pro-China actions, it is worthwhile to question the sincerity of Cayetano’s threats.

In spite of Duterte’s stance, the US remains both the Philippines’ most important security ally. In December 2018, the Philippines requested clarification of its Mutual Defense Treaty with the United States, which was signed in 1951. According to Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana, due to Washington’s inconsistencies in terms of the South China Sea Disputes, the Philippines requires confirmation on whether the US would join arms should current tensions escalate. In response, the US described the alliance as “absolute” and “ironclad,” stating that they would stand by the treaty’s obligations. In an act of goodwill, the US returned the historic Balangiga Bells, taken by the US following the Philippine-American War (1899-1902) just last month. According to Clarita Carlos, a political science professor from the University of the Philippines, the Philippines is not pivoting away from the US; rather, Duterte has widened his potential partners, searching for the route that best serves Philippine interests.

Though Duterte has steered the Philippines towards Beijing, other countries in the dispute have maintained hard-line stances behind their claims. The Vietnamese government has pushed for a pact “that will outlaw many of China’s ongoing activities in the South China Sea. Meanwhile, the Association of Southeast Asians (ASEAN) has been working towards a Code of Conduct for the region. As it stands, little progress has been made in easing the tensions in the South China Sea; with multiple states each vying for their own piece of the region, a universal agreement seems distant, unless states loosen their claims. Given the uncertainty of China’s ambitions, the Philippines should remain strong in its commitment to the drafting of ASEAN’s Code of Conduct and its own claims in the South China Sea. As the Duterte government’s actions regarding the South China Sea has evoked much discontent among the populace, it will be important to the nation as a whole for Duterte to remain vigilant in searching and pursuing the best possible path for his country.

Edited by: Helena Martin