Beyond Whitewashing: Marvel’s Erasure of Tibet in Doctor Strange Supports Cultural Genocide

Artistic interpretation of Doctor Strange https://flic.kr/p/oZdeAe

Artistic interpretation of Doctor Strange https://flic.kr/p/oZdeAe

Tilda Swinton’s casting of The Ancient One for Marvel’s most recent release Doctor Strange is mostly presented as another example of Hollywood’s habit of whitewashing Asian characters in films. This time the issue extends far beyond that, and this is because of The Ancient One’s characterization as a Tibetan person. Marvel’s recent cinematic release Doctor Strange is not only problematic because it whitewashes a character originally of East Asian origin; it’s an intentional erasure of the Tibetan genocide in favour of incurring the maximum potential of profits from the Chinese film market, projected to surpass North America in becoming the world’s largest box office by 2017. To understand this issue one must have a minimum comprehension of the heavily conflicted history between Tibet and China.

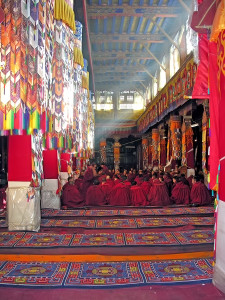

Tibet and China have had tensions between them since as early as the 13th century, but the context of conflict now between the countries starts in 1950, almost 40 years after Tibet declared its independence from China in 1912. In 1950, China sent troops to Tibet and in the next year a Tibetan delegation was called and a treaty was signed, giving China full sovereignty over the country. Tibet’s government is currently exiled out of the country, and is located in India. China takes great care regarding the media that is circulated in its country, and regarding its occupation China presents itself as a leader who has improved the wealthy and quality of life in Tibet. But according to the documentary Tibet Situation: Critical by Jason Lansdell, the reality Tibetans face is far different from these claims. Tibetans are experiencing the erasure of their own culture; for example, they are forced to learn Chinese in schools, and are not permitted to speak their native language. You can find this documentary made available on YouTube, and is also shared on the United Nations for a Free Tibet’s (UNFFT) Facebook page. Police brutality is, perhaps without much surprise, rampant at Tibetan protests (regardless of whether or not violence is present). Tibetan citizens are subjected to imprisonment for unknown reasons, some being released after a period months or years, and to this day have no idea why they were arrested or let go. Friction is further heightened with the Increasing numbers of Han Chinese immigrating to the region, making Tibetans a minority in their own country.

In Doctor Strange, the character the The Ancient One in the comic book series is originally portrayed as a “racist caricature of a wise old Tibetan man” in a pseudo-Tibet that paid little attention to cultural accuracy. Whitewashing was not the best route to take to fix this issue, as adjustments definitely could have been made to make for an accurate portrayal of a Tibetan character. Instead, Marvel changes the character to Celtic, and moves the location from Tibet to Nepal. Swinton’s defense of this casting choice is that “it’s not actually an Asian character…I wasn’t asked to play an Asian character, you can be very well assured of that.” Her explanation is not enough to quell the criticisms many have of erasing Tibet from the picture altogether. China and Tibet have a conflict-ridden history, and given the current tension between the countries there stands no chance that a film with even slight implications of a pro-Tibet statement would make it to screens in China. China’s film industry is known to be rather lucrative for foreign films, as only 34 foreign films are chosen to be played in the country each year, making the stakes high for movies that want to earn big in profits. Marvel in particular has a good history in the Chinese film industry, grossing at $240 million at the Chinese box office. Therefore, it would be in good business for Marvel to maintain friendly relations with the Chinese film industry.

As explained by an article on Screen Rant:

“Before Marvel movies can make their way into China’s theatres, however, they must first undergo scrutiny by the State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television, the government body in charge of approving media for consumption by the Chinese populace, and keeping an eye out for any scenes that could be perceived as portraying China, the Chinese government, or the Chinese people in a negative light.”

The consequences of breaching these rules is no light matter. China banned Brad Pitt and other main contributors to the film from entering the country because of their role in the film Seven Years In Tibet, which portrayed the Dalai Lama under a sympathetic light. Tibetan erasure is an intensely and thoroughly conducted procedure, and extends far beyond the world of the film industry. The reluctance to take a widely-pronounced stance against China can be seen in the political sphere as well. Due to China’s influence in the film industry and its role as a super power in foreign trade, countries would lose out on the benefits of maintaining good social and economic relations with China’s government. A small exception to this pattern has occurred when President Barack Obama arranged a private meeting with the Dalai Lama in the Oval Office, which is normally reserved for meeting with visiting heads of state or other government leaders. For Obama to do this is definitely unique, and although it was released that “a range of issues, including human rights” would be discussed, no further details were provided. China’s reaction was definitely negative, with its officials harshly criticizing this meeting as a decision that could legitimize the idea of Tibetan independence from China. Although an honourable step outside the status quo, efforts to appease China are evident with the White House Press Secretary’s statement that insisted the meeting was “a personal greeting rather than formal bilateral talks”, reassuring that “Tibet, per US policy, is considered part of the People’s Republic of China.”

The situation in Tibet is rather bleak. Not only do they not have the forces to adequately oppose China’s power, but the Chinese population is taught to believe that Tibet is not an independent state, best belonging to the larger country. Also, the Chinese government enforces a strict control on the media, barring access to information to any media critical of China and its rule. In the West, state leaders and government official of countries like the US deem that a public condemnation of China’s mistreatment of the Tibetan people holds consequences too dire for their countries to stand. In such a case, the genocide of the Tibetan population will continue without the outer world doing so much as taking a second look. But unlike the common people of China and Tibet, countries that give its people rights to freedom of speech and assembly have the power to unearth the atrocities that Tibetans have had to face. Arousing empathy and a call to action for a country so estranged for others such as Tibet would be far more feasible were there more mainstream sources of media that explicitly illustrated the Tibetan struggle. The television series Avatar: The Last Airbender subtly features elements of the Tibet-China conflict through fictionalized but analogously created groups in a way that western consumers can relate to and therefore sympathize for these minority groups. It has never been officially discussed by show creators, but on many forums and fan pages of the show it is widely accepted that the group called the Air Nomads are primarily based off of Tibetan culture. More explicit characterizations of this story are needed to not only inform but motivate groups to collectively activate for freedom in Tibet. Media cleansing through means similar to Marvel’s production of Doctor Strange is a significant obstacle blocking our way from achieving such goals.

In response to the whitewashing accusations, Doctor Strange screenwriter C. Robert Cargill stirred up some controversy when he stated in an interview on the show Double Toast:

“He originates from Tibet, so if you acknowledge that Tibet is a place and that he’s Tibetan, you risk alienating one billion people [and run the risk of] the Chinese government going, ‘Hey, you know one of the biggest film-watching countries in the world? We’re not going to show your movie because you decided to get political.’”

Shortly thereafter Cargill apologized, saying that his statements on the show did not represent Marvel and claiming that no one at Marvel or anyone working with him in the production of the movie ever discussed the Tibet-China conflict with him. This poorly packaged cover-up does not change the fact that Cargill is wrong in saying that Tibet from the movie was to avoid being political. Such a decision is indisputably political; the choice to change the location to Nepal and The Ancient One to Celtic is an active choice to remain silent when given the chance to stimulate mainstream awareness and discourse on the current existence and status of Tibet and its people. Marvel films already make on average total gross earnings of $206 million in the US box office alone; but seeing as Avengers: Age of Ultron grossed $240 million in China, why would Marvel want to bite the hand that overfeeds them?