Blaming Violence on Mental Illness: A Lose-Lose Situation

Picture of a Gun as a proxy for violence.

https://bit.ly/2uEK7HY

Picture of a Gun as a proxy for violence.

https://bit.ly/2uEK7HY

In North America, the treatment of individuals suffering from mental illness has shifted dramatically over time. From institutionalization to de-institutionalization to our current middle ground of stigmatization, one element has remained constant: the societal perception of those with mental illness. Despite shifting treatment standards, society has continued to hold onto the general idea that those who suffer from mental illness are dangerous, and perhaps even the most violent members of society. This deeply-held notion can be seen through the variety of deviant acts which are continuously blamed on mental illness. Only recently, when a gunman killed 17 in a school in Parkland, Florida, policymakers and media were quick to describe the mental state of the shooter. However, being so quick to blame violence on mental illness provides little benefit, and can instead be detrimental to society. Using mental illness as a scapegoat only serves to further stigmatize those who suffer from mental illness and make it harder for society to identify and tackle the real root issues of violence.

Firstly, what is mental illness? As defined by the American Psychiatric Association, “mental illnesses are health conditions involving changes in thinking, emotion, or behaviour (or a combination of these). Mental illness is associated with distress and/or problems in functioning in social, work or family activities.” As of now, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the formal manual used to categorize mental disorders in North America, recognizes 265 disorders. The assumption inherent in creating this many categories for mental disorders is that they each represent a distinct pattern of behaviour and functioning. It is thus critical to understand that mental illness does not refer to just one entity. Suffering from depression is not the same as having ADHD, and having ADHD is not the same as having antisocial personality disorder. In fact, even two people with the same disorder may not exhibit identical patterns of behaviour. This is known as heterogeneity, which is the idea that two people can meet criteria for the same disorder despite displaying a different grouping of symptoms.

Mental illness as a whole is actually quite common. In any given year in Canada and the United States, nearly 20 percent of individuals are living with a mental illness. As such, when deviant behaviour and violations of social norms are labelled as being caused by mental illness, this supposed blame falls not on a small subsection of the population, but instead on a large group of people.

Because those suffering from mental illness have historically been labelled as dangerous, it is intuitive to question whether there is merit to that idea. Simply put, are people who suffer from mental illness actually more dangerous, and thereby violent? The simple answer is: not entirely. Overall, there is an association between mental illness and likelihood to be violent. However, the association is only slight, meaning that, while compared to the general population, those with mental illness seem more at risk of violent behaviours, but the actual risk is still very small. In fact, only about only 3 percent of violent crimes are attributed to those with mental illness. In terms of gun violence specifically, the number drops to just 1 percent.

Because the stakes of this generalization are so high, it is important to unpack it even further. Firstly, the findings present an association, and not necessarily a causal relationship. This means that it remains unclear whether mental illness predisposes someone to be violent, or whether someone who is already predisposed to be violent may be more likely to have mental illness. Essentially, there is no conclusive evidence to indicate that mental illness causes violence. Furthermore, a recent study in 2009 found that mental illness alone did not predict violent behaviour. Rather, the study found that violence was associated with other factors, such as history of abuse, certain demographic and dispositional factors, such as age and socioeconomic status, and substance abuse. Substance abuse was found to be the most highly correlated factor. In fact, most studies that do find an association between mental illness and violence also find that at least some of that relationship can be explained by substance abuse.

It also remains unclear why the relationship between mental illness and violence exists. It remains disputed whether the association is the result of a direct relationship or whether other factors mediate the association. As for predicting violence more generally, factors like age, gender, and ethnicity (most likely due to socioeconomic status), are stronger predictors of violent behaviour than mental illness. Again, even with this association, only a small percentage of those who suffer from mental illness exhibit violent behaviour. Furthermore, because mental illness represents just a portion of the general population, only a very small percentage of perpetrators of violence also happen to be mentally ill. All this to say that the link between mental illness and violence is minor, is likely not the root cause of violence, and is certainly not the only contributor to violence.

What is often seen depicted in the media and in government is an incorrect causal inference between mental illness and violence. However, what further gets overlooked is the fact that those who suffer from mental illness are significantly more likely to be victims of violence as compared to the rest of the population. It has been found that over 25 percent of those who suffer from a severe mental illness are victims of violence; a rate that is more than 11 times that of the general population. Some studies even find that those suffering from mental disorders are at an increased risk of dying from homicide. There is also an association between mental illness and suicide. Statistics Canada states that “more than 90% of people who commit suicide have a mental or addictive disorder.” This is a noteworthy number given that suicide is the 9th leading cause of death in Canada. However, it is important to note that mental illness doesn’t necessarily cause suicide and that the majority of mental illness sufferers do not die by suicide. Nonetheless, being victims of violence and of suicide is a significant concern for populations suffering from mental illness. This serious issue should not be ignored in favour of discussing the minimal risk of violence being perpetrated by those with mental illness.

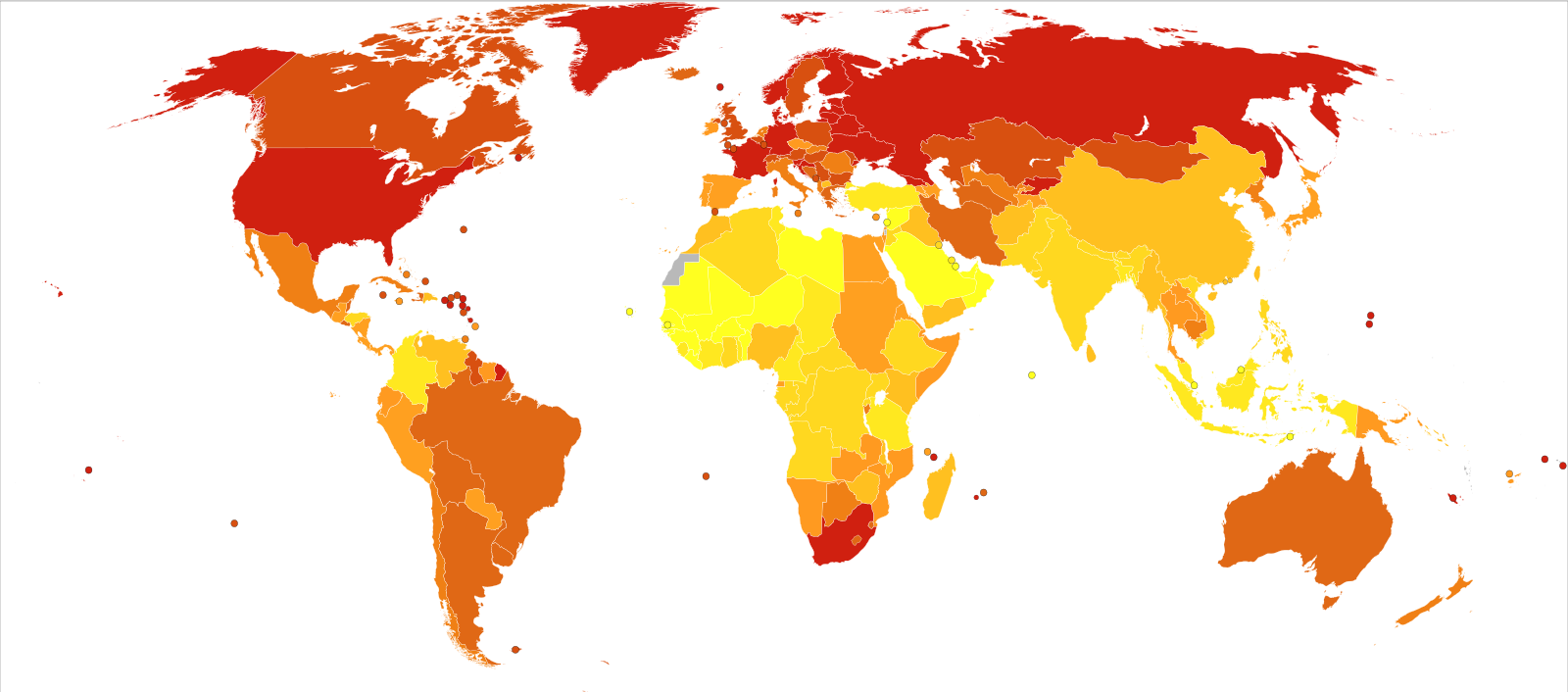

Nonchalantly blaming violence on mental illness represents an ignorance to the bodies of scientific evidence that point to other factors more deserving of attention. Using this language further stigmatizes individuals suffering with mental illness. The World Health Organization has created extensive reports on ways to prevent violence, which are based on thorough research into the root causes behind violence. According to these reports, society would benefit from focusing on parent-child relationships, life-skill training for children and adolescents, harmful alcohol usage, weapons (including guns and pesticides), gender equality, and socio-cultural norms regarding violence and victim identification. This is not to say that all violence will end by targeting these factors; however, each of these contributors deserves attention, and this need is ignored if every major violent act is blamed on mental illness.

As Emma McGinty, professor of health policy at John Hopkins University stated, “Anyone who kills people is not mentally healthy […] but it’s not necessarily true that they have a diagnosable illness.” This reflects the essence of the change in societal norms that is desperately needed. We must accept that violence is a serious issue deserving of attention, without forgetting that its causes are complex and multifaceted and not simply “caused” by mental illness. Only once this shift in perspective occurs can we truly hope to see improvement in the severe levels of stigmatization and marginalization faced by the community of people with mental illness.

Edited by Catharina O’Donnell