Bolivia 2020: Legacy and Leftism in Luis Arce’s Victory

Mercha a favor de Evo Morales – Buenos Aires by Santiago Sito is licensed under CC by 2.0

Mercha a favor de Evo Morales – Buenos Aires by Santiago Sito is licensed under CC by 2.0

According to local legend, the Bolivian administrative centre of La Paz is home to “Elephant Cemeteries” — places where people go to drink themselves to death. These “bars” service the desperate and downtrodden, tying into another local legend — contemporary human sacrifice. While these stories are hard to confirm, unfortunately, they still cast a lens of suspicion over the traditional practices of the nation’s Indigenous population. This sentiment of distrust between Indigenous Bolivians, accounting for 40–60 per cent of the population, and the non-indigenous minority, is not a new phenomenon. In fact, until 1952 — 127 years after the country gained liberation — Indigenous Bolivians were not considered citizens. Furthermore, it wasn’t until 2005 that Bolivia elected its first Indigenous leader, Evo Morales.

In October 2020, a year after Morales was forced out of office, his handpicked successor, Luis “Lucho” Arce, seemed especially poised to bring his party back into power. While the October 2019 election briefly signalled Morales’ victory and re-election, the results immediately gave rise to controversy. Because Morales had been elected three times before, despite Bolivia’s constitutional two-term limit, which he unsuccessfully tried to change through a 2016 referendum, nationwide protests erupted regarding the electorate’s suspicions of fraud. Shortly thereafter, in what many consider to be a coup, Morales was forced to resign, and subsequently fled to Mexico. Since then, Bolivia has been under the direction of interim president and former opposition senator Jeanine Añez, who has reportedly referred to indigenous traditions as “satanic.” Añez promised to hold an election shortly after seizing power, but postponed it three times due to coronavirus concerns. She finally called an election for October 18 after widespread protests, led by “trade unions and social movements,” broke out in August. As interim president, Añez worked to reintroduce Catholic symbols into the government, while prosecuting her predecessor’s supporters. Upon installation, she went so far as to declare that “the Bible [had] re-entered the palace” and charged Morales with terrorism.

Since the de-facto regime has been in power, Bolivia witnessed repression against workers, unions, journalists, and supporters of Morales’s party, the Movimiento al Socialimso (MAS). Añez’s economic policies, often described as a “return to neoliberalism,” and the use of military forces damaged the economy, diminishing her popularity. In September, she dropped out of the presidential race, ostensibly to focus on uniting Bolivia’s conservative factions against Luis Arce, a leftist and former minister of the economy. In the wake of Añez’s concession, Arce’s primary rival was Carlos Mesa, a former right-wing president, who has moved further left because “Morales shifted the entire spectrum…to the left,” according to Texas A&M’s Diego von Vacano. Both candidates’ more-or-less leftist inclinations is a testament to Morales’ immense influence on Bolivian politics and society. That legacy proved invaluable on October 18th, with initial exit polls showing a massive MAS lead with Arce claiming victory shortly after. Mesa conceded the race on the 19th, stating his wish that “those who believe in democracy recognize the results.”

In this election, Arce’s victory signals a return to socialism and an explicit rejection of Añez’s government and policies. Following the initial results, Arce was quoted as saying that “[The MAS] are going to govern for all Bolivians and construct a government of national unity.” Arce is considered the architect of the Bolivian Miracle: 14 years of steady economic growth, reduction in poverty and inequality, as well as the nationalization of several sectors of the country’s industry. As the premier candidate for the MAS, Arce has a strong base of dedicated supporters, especially among the Highland Indigenous groups, coca growers, and other leftist factions. The two former groups have been an important factor in MAS’s success — Morales himself was the head of a coca growers union — and they have fought for the right of Indigenous Bolivians to cultivate coca, despite US opposition. Arce’s stated intentions t0 protect coca growers and nationalize Bolivia’s valuable lithium deposits, therefore represent a return to Morales’ strong socialist ideals and an unwillingness to be controlled by western powers, especially the United States. Lithium is particularly contentious, as it is highly sought after by private corporations, and much of it is located beneath the iconic “Salar de Uyuni,” the world’s largest salt flat.

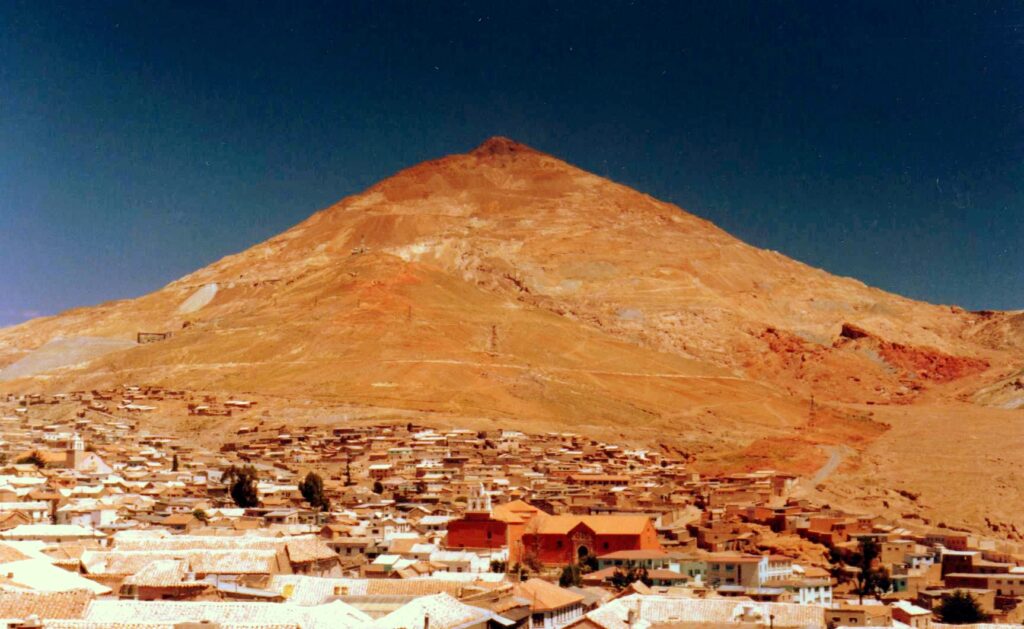

As a Spanish colony, Bolivia was primarily used for resource extraction, with the “man-eating” Potosi silver mine, Cerro Rico, as its crown jewel. This mine, which still in operation today, is said to have a historic death toll of eight million Indigenous Bolivians and African slaves. As such, Potosi is a prime example of the traditional stratification of colonial Bolivia — Spanish wealth at the cost of Indigenous lives. Moreover, the Spanish established a caste system that further divided the country and enforced Aboriginal groups’ conversion to Catholicism, giving rise to the suppression and vilification of traditional practices. This exploitative relationship largely persisted until Evo Morales’ victory in the 2005 election. As a champion of the indigenous cause, Morales promoted traditional practices, leading to resentment among the non-indigenous minority, many of whom now view themselves as the disenfranchised. Likewise, his focus on racial politics earned him the ire of the European faction, further contributing to the division of the country.

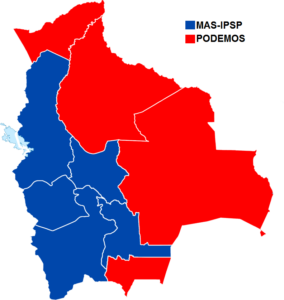

In Bolivian politics, ethnicity is a salient topic. There are more than 30 Indigenous groups in Bolivia, ranging from small groups in the lowlands to the Quechua and Aymara of the Andean highlands. In light of such notable diversity, the Indigenous peoples of Bolivia are not a politically homogeneous mass. The Aymara and Quechua, who make up roughly 80 per cent of Bolivia’s indigenous majority, typically vote for leftist parties with pro-indigenous platforms like the MAS, which highland groups often trust as being the best option to represent their interests. Because these two groups are so much larger than any other aboriginal group in Bolivia, they are sometimes falsely viewed as a synecdoche for Bolivia’s Indigenous population as a whole, in terms of both policy and cultural imagination. However, there is a considerable contrast between the highlands’ voting patterns and those of the lowlands, where the centre-right is preferred.

Much of the divergence between the highlands and lowlands of Bolivia traces back to their differing experiences under colonization. The highlands were — and still are — the sight of the massive Spanish mines that operated in the colony, like the aforementioned Cerro Rico. The Quechua and Aymara were used as expendable labour and were forced to pay exorbitant taxes to maintain the state. As a result of that oppression, the highlands have long played host to protest and leftist organization. Because of this, and the concentration of the Andes’ population, the highlands have historically been the more vocal political force. In contrast, the lowlands have long remained less integrated into the Bolivian state, wherein colonial administrators treated these lands like “empty” real-estate by redistributing among wealthy cattle farmers who represented the European elite. Because the population that inhabited this region was small and more dispersed, the identities of the lowland Indigenous didn’t gain the same political salience as their highland counterparts. The military dictatorships of the 60s and 70s were the first to court and integrate Indigenous supporters from the lowlands, creating an opening for the dissemination of far-right ideals in the region. Those ideals, coupled with the perception that highland interests dominate left-wing parties and their agendas, continues to resurface in contemporary Bolivia, especially in the context of lowland indigenous voting patterns.

Bolivian democracy cannot exist without the input and involvement of its Indigenous constituencies. In 2020, the stakes were particularly high for Indigenous Bolivians, who continue to confront colonial exploitation in the form of contemporary practices like extractivism, which Morales fought against. Arce’s intention to continue this fight, especially regarding lithium deposits, therefore implies a broader commitment to ensure that Bolivia will not relive its colonial past.

Bolivian elections have long been considered a “referendum of socialism in Latin America.” The 2020 election can also be seen as a referendum on modern-day resource exploitation in a mostly indigenous space. With Arce’s victory, Bolivian voters expressed their support for socialism, laying the foundations for a new era of unity and growth.

Feature image: Pro-Morales demonstration following the 2019 election. Marcha a favor de Evo Morales – Buenos Aires by Santiago Sito is licensed under CC by 2.0.

Edited by Teresa Tolo