Can Trustbusting Solve America’s Inflation Problem?

Despite skyrocketing meat prices, ranchers are struggling financially, with some considering leaving the business. "Archer County Rancher Doug Dunkel" by USDA NRCS Texas is under license CC BY 2.0.

Despite skyrocketing meat prices, ranchers are struggling financially, with some considering leaving the business. "Archer County Rancher Doug Dunkel" by USDA NRCS Texas is under license CC BY 2.0.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that a global pandemic is tough on the economy. In 2020, the American economy shrank by 3.5 per cent, marking the worst year for economic growth since the start of the post-war period. Since then, there has been a significant rebound: 2021 saw the economy balloon by 5.7 per cent, the largest increase since the early 1980s. Yet, both the American and international economic situation remains precarious. America needs to add 8 million more jobs to catch up with pre-pandemic growth trends, a task which will only become more difficult as federal stimulus wanes in response to a 40-year inflation high.

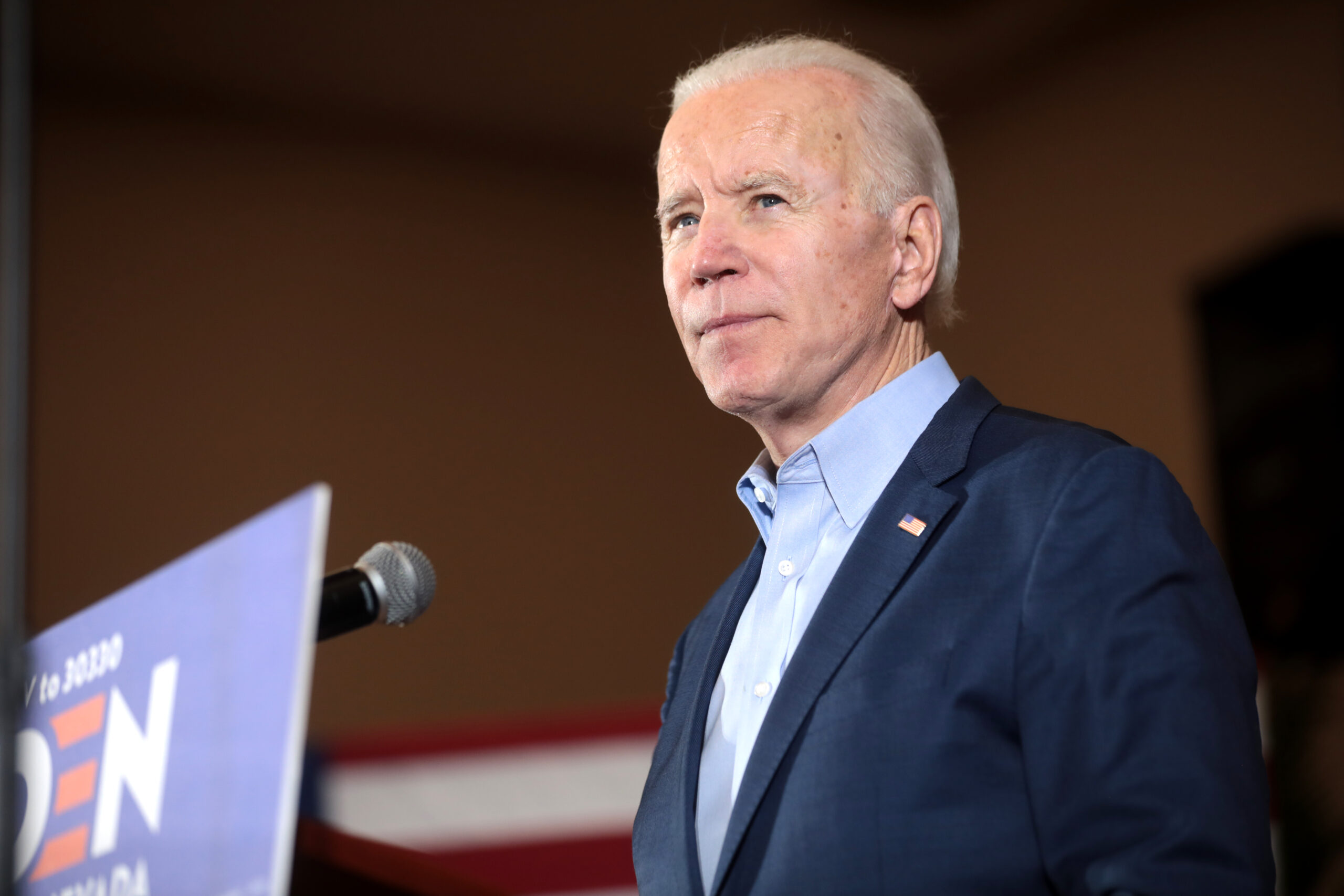

Inflation has become the primary concern for American voters, who are tired of paying more for groceries, gas, and other essentials. Higher prices have translated into lower approval ratings for the Biden administration, which has sought to point the finger of blame — at least in part — at market monopolies that reduce competition and give corporations the power to drive up consumer costs. The logic is intuitive: if you control the market, you control the prices too. Biden’s strategy has involved pursuing antitrust policies that strengthen legislation to prevent mergers, promote competition, and prevent corporate giants from dominating the market.

The meat monopoly

The move to strengthen antitrust laws has spotlighted the dearth of corporate competition in the meatpacking industry in particular. Consumer prices for meat and poultry rose 13 per cent between 2020 and 2021, with pandemic-related supply chain bottlenecks frustrating record demand. Yet, meat producers — the farms and ranches that raise the animals for slaughter, many of them generations-old family-run operations — haven’t seen an increase in profits from these higher prices. Instead, the meatpacking giants are lining their pockets, having tripled their profit margins while the pandemic gutted consumers and small businesses.

Thanks to a wave of mergers to consolidate market shares beginning in the 1980s, four companies dominate slaughter, processing, and packing in the poultry, beef, and pork industries in America today. By gradually edging out the competition, these corporations have developed the power to dictate both prices for the entire meat market and pay for meatpacking employees and ranchers. Their consolidated corporate power allows these giants to reap profits by disadvantaging both consumers and producers. According to the administration, they are doing so even in the middle of a pandemic that has drained wallets and facilitated inflation.

Of course, ‘Big Meat’ denies any profiteering or exploitative behaviour toward producers, stating that higher meat prices are linked solely to scarcity. The virus drastically hampered meat production when it tore through slaughterhouses in the first year of the pandemic, leading to shortages the industry is still trying to recover from. Inflation is exactly what happens when demand far outstrips supply — as is the case with record levels of demand for poultry, pork, and beef.

Alternatively, Biden and other senior Democrats, including Senator Elizabeth Warren, suggest that sky-high prices are both the expected result of inflation and the product of corporate profiteering by monopolies. These corporations are marking up their products even more in the absence of competitors, using inflation as a convenient cover. The recent push to strengthen antitrust laws, then, seeks to create more competition in all sectors of the American economy, with the aim of unseating these sorts of corporate giants and empowering smaller companies as challengers.

Low competition, high push-back

Although there is an apparently intuitive logic to the antitrust policies Biden is proposing to address inflation, things are rarely as simple as one would like them to be — least of all economics. The administration is facing plenty of criticism and push-back in response to its antitrust focus. And not just the expected resistance from the conservative opposition; many progressives remain unconvinced too.

A lot of the backlash towards Biden’s anti-inflation strategy accuses the administration of fundamentally misunderstanding inflation, which Republicans argue is caused by sustained shortages rather than uncompetitive markets. Monopolies aren’t new, but these levels of inflation are. Thus, it can’t be proven that industry giants like Tyson Foods are exploiting the pandemic rather than just reacting to economic pressures.

Conservatives are right in arguing that the current economic strain is clearly and directly linked to pandemic-related problems, at least in part. Labour shortages and supply chain issues amidst rising consumer demands are contributing to inflation. It’s also difficult to make a convincing case that corporate greed is substantially responsible for America’s current economic woes, as legislators can’t read the minds of industry executives. Conservatives, in particular, accuse Democrats of trying to escape public dissatisfaction by passing off the blame for inflation on corporate monopolies.

The White House acknowledges that antitrust policies are unlikely to bring immediate relief in the form of reduced costs for businesses and consumers, claiming the benefits will materialize further down the line. But Biden’s focus on antitrust legislation as a means of increasing economic competition predates the dramatic rise in prices: recent antitrust moves and monopoly-maligning seem less like Democratic blame-shifting and more like Democratic opportunism.

However, this approach is not necessarily a bad idea. High inflation has presented an opportunity for Democrats to pursue policies they’ve advocated for decades. Since the Reagan era, US economic values have tended to favour a laissez-faire approach, with minimal regulation and a lax approach to antitrust inspired by the idea that consumers benefit from the market success of large companies. Yet, in the absence of stronger regulation to discourage anti-competitive behaviour, companies have been able to edge or buy out their competitors and consolidate market power. Attaining monopoly status affords them the power to mould the market to their own interests at the expense of consumers.

Biden explained along these lines that “capitalism without competition isn’t capitalism. It’s exploitation.” Whether one loves it or hates it, capitalism has been firmly established as the ruling doctrine of the American economy for hundreds of years — a fact that’s unlikely to change anytime soon. So, the administration might as well make the best of it. Stronger antitrust legislation has the potential to decrease anti-competitive behaviour and empower oversight of exploitation and abuses by large corporations, freeing markets — and consumers — from the grip of greed-driven monopolies.

The pandemic has brought innumerable social, political, and economic challenges. One of those hardships is inflation. We have labour shortages and supply-chain snarls to thank for high prices, and until industries manage to recover from these setbacks and catch up with demand, our wallets are unlikely to get much relief. But if this fraught period in history also gives rise to stronger antitrust laws and a more competitive economy, I think we could call that a bright side.

Edited by Rory Daly.

Feature image, “CattleRancher_011a copy” by K-State Research and Extension is under license CC BY 2.0.