Canada in the Post-Pandemic World

"G7 Summit flags" by UK Prime Minister is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

"G7 Summit flags" by UK Prime Minister is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Nearly one year ago, Canadians were in the midst of a tense election cycle. The cost of living, taxes, climate change, housing, and wages were the most pressing issues for Canadians at the time. Since then, the world has turned upside-down. In Canada alone, nearly ten thousand have lost their lives and over 5.5 million have lost their jobs or faced reduced employment because of COVID-19. In light of this sudden and significant change to society as we know it, Justin Trudeau’s throne speech on September 23 outlined four priorities for his government —COVID-19 safety, economic stimulus, “building back better,” and a more inclusive Canada. Towards the end of the speech, a few lines are dedicated to “Canada in the World,” offering familiar themes of openness to trade, condemnation of China’s arbitrary detention of Canadian citizens, and the need for a global response to COVID-19. Though significant analysis has been dedicated to the major social and economic concerns, Canada’s foreign policy remains relatively unexamined. COVID-19 presents Canada with a historic opportunity to reimagine its international relationships, and show leadership through multilateralism to fight the crisis of climate change.

A snapshot of Canada’s recent foreign policy

After his 2015 election win, Justin Trudeau’s government sought to reclaim Canada’s peacekeeping, multilateral, and human rights-oriented foreign policy. Almost immediately, however, significant geopolitical events challenged this goal. Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the rise of China have contradicted the prevailing international rules-based order and have left Canada with few friends attempting to defend liberal internationalist values on the global stage. Despite this, Trudeau’s government has achieved some success, including the renegotiation of NAFTA, the signing of new free trade agreements with the EU and Asian-Pacific countries, and the introduction of Canada’s first feminist foreign policy. However, the Liberals have also faced considerable setbacks. Despite lobbying Canada’s allies, Trudeau has been unable to free hostages taken by China in response to the detention of Huawei’s CFO, Meng Wenzhou. Canada also lost out to Norway and Ireland in its bid to join the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).

Erin O’Toole, the recently-elected Conservative Party leader, has made foreign policy a priority. Most notably, O’Toole has advocated for a hawkish approach to China by proposing sanctions on members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), banning Huawei, and creating new economic alliances with democratic countries to reduce Canada’s economic dependency on China. In his view, China’s export of authoritarianism is the greatest threat to the rules-based international order. This represents a notable departure from his predecessor, Andrew Scheer, whose post-election priorities in December 2019 were entirely domestic.

Though all Canadian parties seek to distinguish themselves from each other, Canada’s foreign policy has remained remarkably consistent. While it is true that, in general, the Conservatives are traditionally more interventionist, and the Liberals emphasize their commitments to UN Peacekeeping, Canada’s underlying commitments to multilateral institutions and human rights have not significantly changed since the Second World War. As former Foreign Minister Chrystia Freeland put it, “Whatever their politics, Canadians understand that, as a middle power living next to the world’s only superpower, Canada has a huge interest in an international order based on rules… one in which more powerful countries are constrained in their treatment of smaller ones by standards that are internationally respected, enforced, and upheld.”

It is rather unsurprising that the Liberal government’s Throne Speech, “A Stronger, More Resilient Canada,” recommits to multilateralism and bolstering the ever-fragile international order. Yet, this pandemic calls for anything but more of the same from our political leaders. Canada continues to be subject to the whims of the United States and China, who have proven to act in bad faith when it suits them. The global fight against climate change has been put on the back-burner, and has few champions on the global stage. Canada’s international clout continues to slide, as evidenced by its loss at the UNSC. In the face of these problems, Canada can and must try to rethink its place in the world.

Make Canada relevant again

Middle powers, in a perpetual state of seeking prosperity and recognition abroad, rely on national branding to, among other things, attract investment, promote exports, and lead on the world stage. Improving Canada’s national brand is not about making it more famous, but rather about making itself more relevant to the world and its needs. What would making ourselves more relevant in today’s pandemic-stricken world look like? In the short-term, this would mean exporting personal protective equipment, mobilizing Canada’s medical expertise to countries that desperately need it, and financing an equitable vaccine distribution on a global scale. It would also be constructive to lay the groundwork now for diversifying our trading partners across the world once the global economy recovers. In 2018, the United States and China, constituted 75 per cent and 4.75 per cent of Canada’s total trade, respectively. O’Toole’s suggestion that Canada pivot to India, Taiwan, and nations of the former British commonwealth are certainly interesting paths to take. In the long-term, however, Canada must be focused on being relevant in the most pressing crisis of the century: climate change.

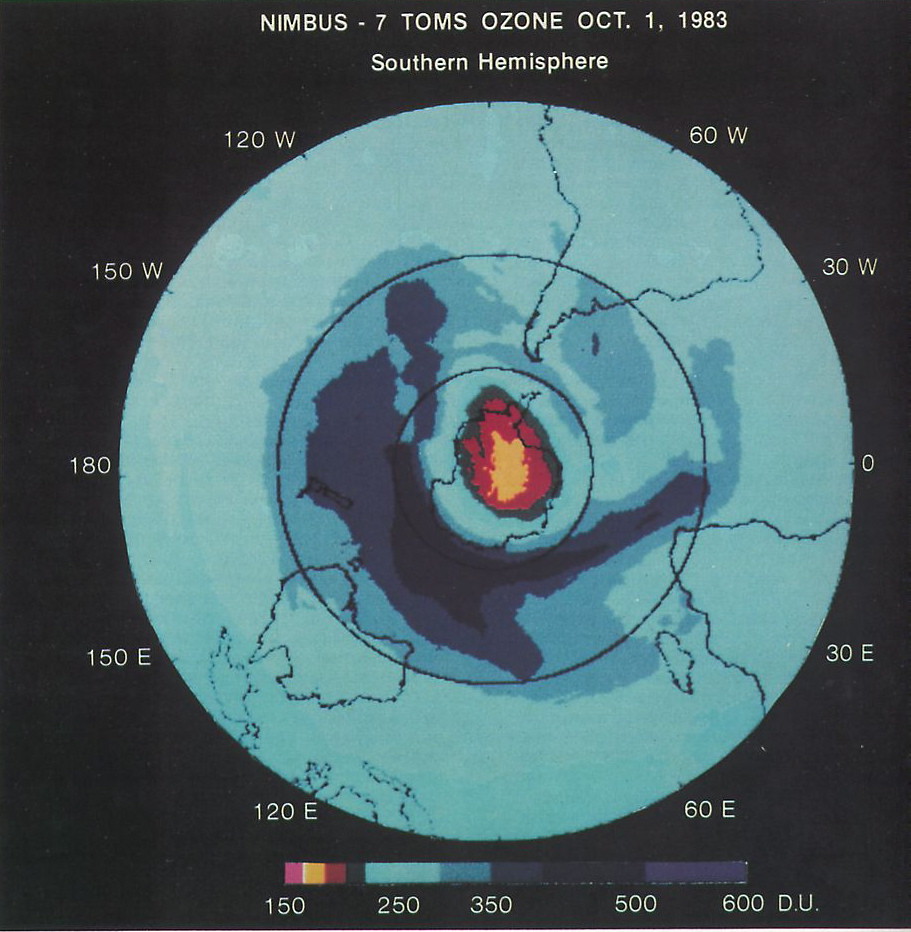

Climate change already threatens many countries, and in the coming years, its disastrous effects will become even more apparent. In the face of such a complex issue, it is easy to be cynical about what the international community can do. The Montréal Protocol of 1987 is an example of what Canadian leadership is capable of achieving in the face of daunting environmental problems. By persuading like-minded allies, and pushing for the conference to be held in Montréal, Progressive Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney was instrumental in creating the protocol. The treaty lowered emissions by an estimated 135 gigatonnes of CO2 by effectively banning ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), thereby avoiding a warming of almost 0.5° celsius. Having a tangible, realistic objective improves the efficacy of international cooperation. For the 1980s, that objective was the elimination of CFCs. If Canada is serious about fighting climate change through multilateralism, it should take inspiration from its past and lead an international effort to phase out certain fuels that disproportionately contribute to greenhouse gas emissions.

Coal is a prime target for international regulatory efforts. Like CFCs, coal has an outsized effect on emissions, but importantly, with appropriate funding for technology it can be easily substituted for greener alternatives. Coal used in electricity generation accounts for 30 per cent of the world’s CO2 emissions, and is particularly high in industrializing nations such as China (72 per cent of emissions), and India (64.5 per cent). A new treaty similar to the Montréal Protocol that phases out coal from global energy generation would be transformative in the fight against climate change – a global fight in dire need of leadership.

As Canada’s political leaders prepare to rebuild Canadian society in the wake of the pandemic, we cannot afford to waste this opportunity to rethink our role in the World as well. Trudeau’s Throne Speech recycles worn talking points on multilateralism, trade, and the rules based order. If Canada is to defend these values, we must fight to stay relevant in the global conversation. In his address to the UN General Assembly, the Prime Minister remarked that “The world is in crisis, and things will get a lot worse unless we change…right now we have a chance to shift course.” Today, that means Canada must show its compassion in this pandemic to those nations that need it most. Tomorrow, that means strengthening economic and strategic partnerships with fellow middle powers. But in the post-pandemic future, Canada must expand its thinking and tap into its legacy of international treaties to fight climate change and secure a better future for all.

Featured image: “G7 Summit flags” by Number 10 (UK Prime Minister) is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Edited by Nina Russell