Canada’s Dual Stance on Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Amman, Jordan. Photo: Jamie M Brown

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Amman, Jordan. Photo: Jamie M Brown

Canada has always seen itself as a defender of human rights. It was Lester B. Pearson, Canada’s “foremost diplomat” and prime minister from 1963-68, who first proposed the idea of a United Nations Peacekeeping force. In the decades since, Canada has strived to establish itself as a strong proponent of international cooperation, most notably participating in a number of peacekeeping missions and playing an instrumental role in the creation of the International Criminal Court. In addition to encouraging other states to make similar commitments, Canada speaks out on human rights violations carried out by other states, a recent example being the incident with Saudi Arabia, wherein Canada denounced the Saudi government’s arrest of two women’s rights activists.

Despite an apparent commitment to upholding the values of international peace and cooperation, Canada continues to maintain diplomatic relationships and economic partnerships in the form of trade and arms deals with states who are in direct violation of these principles. The ability to turn a blind eye to human rights concerns in favour of economic gain is a tendency that demonstrates the selective nature of Canada’s “progressive” foreign policy.

That being said, these arms deals benefit the Canadian defence industry, which in 2016, contributed $6.2B to the country’s GDP. Stepping away from even one of these deals would undoubtedly have serious repercussions. In addition, these deals are important instruments in maintaining relationships with allies, including many NATO countries. Strategic relationships are key to Canada’s influence at the UN and are necessary for obtaining favourable political and trade agreements. Whether it is right for Canada to remain in these partnerships depends on if the economic benefits outweigh the cost of sacrificing the values Canada has publicly espoused.

Canada as a Human Rights Leader

With domestic and international statutory human rights codes, there are a variety of mechanisms with which Canadians can ensure fair treatment and protection. It would be incorrect, however, to suggest that these have always been successful. As organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have reported several times, there continue to be serious domestic violations of these codes, pertaining especially to Indigenous populations. One of the most significant cases is that of roughly 1,017 reported missing or murdered Aboriginal women, which the government failed to recognize or act on for years. As a result, a number of states, including Saudi Arabia, North Korea, and Iran, have remarked on Canada’s inconsistent domestic violations and foreign policy.

Canada has followed the lead of the UN with respect to imposing sanctions on states who commit atrocities against their citizens and those of other countries. In principle, it is careful about who it partners with, particularly concerning weapons sales. In 1998, the Cabinet approved policy guidelines that “closely [control]” the export of military technology and materials to countries which have a history of human rights abuses. Regardless, Canada is involved in a series of multi-billion dollar arms deals with countries who have repeatedly violated these conditions.

Canada and Saudi Arabia

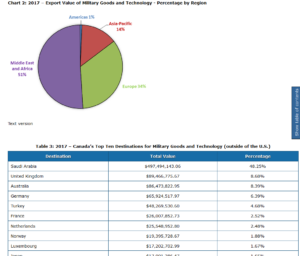

The arms agreement with Saudi Arabia has been among the most controversial of such deals. The dispute between the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) and Canada in August highlighted the questionable trade agreement between the two countries- it is Canada’s second largest client for military goods and equipment, comprising 48% of exports outside of the USA, a total of $497.5 million. This is an exorbitant amount to be exporting to one country in any circumstance, but even more so considering the blatant human rights abuses that the KSA is known to carry out, including arresting journalists and activists, crushing minority Shia uprisings, and most importantly, being overtly involved in the world’s worst humanitarian crisis in Yemen.

A report by UN investigators stated that violations of international humanitarian law in Yemen “may amount to war crimes”. Canada, which counts freedom of speech as one of its core values, is unapologetic in its partnership with a state that has detained the owners of domestic media outlets, regularly silences dissidents, and is currently embroiled in an investigation into the murder of a prominent Saudi journalist and political commentator, Jamal Khashoggi, which the KSA has admitted was done by its government officials.

In what has become almost an ideal case study, the Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, responded to a question about Khashoggi with a rather ambivalent statement, commenting that “this particular case is of course of concern” and that Canada is “expressing serious issues” with the reports received so far. Following a question about the arms deal with Saudi Arabia, he responded, “The previous government signed a contract […] to sell armoured vehicles […] we are making sure Canadians’ expectations and laws are always being followed”. Though this response is remarkably mild considering the suspicious death of a journalist, it is not surprising. Trudeau has repeatedly attributed the deal to former PM Stephen Harper’s government, insisting that the deal was signed and must therefore be fulfilled.

There are legitimate reasons to suspend or cancel this deal. Under Canada’s export policy, there are restrictions pertaining to the export of military goods to governments with a “persistent record of serious violations of the human rights of their citizens”. According to the Country Report on Human Rights Practices for 2017 report by the US Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labour, Saudi Arabia more than fulfills these criteria. Partnering with a state carrying out such violations is not only hypocritical but diminishes Canada’s credibility internationally when championing human rights causes.

Canada and Turkey

Since an attempted coup in 2016, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been openly carrying out extrajudicial killings targeting civil servants, the military, lawyers, media personalities, and academics. According to the NATO Association, up to 130,000 citizens have been detained. The same report states that Turkey is now the “leading jailer of journalists worldwide”. Additionally, the Turkish government has been engaged in a struggle for decades against its Kurdish minority, which makes up 25-35 million of the country’s population, but are prevented from self-rule and consistently suffer persecution from Turkish forces.

Last July, Chrystia Freeland, the Canadian Minister of Foreign Affairs, issued a statement on Turkey, stating that she was “seriously concerned about the current detention in Turkey of democratically elected officials, journalists, academics and human rights defenders”. Notwithstanding, the Canadian government has released statements affirming the legitimacy of the Turkish government “Any factions attempting to use force to undermine Turkish democracy should stand down immediately “. This also contrasts statements like Trudeau’s this year- “Canada will always… stand against any violence, intimidation, censorship, and false arrests used to silence journalists”. In the same year, Canada exported $48,269,530 of military goods and technology to Turkey, making it the country’s 5th largest trading partner, again suggesting a superficial quality to Canada’s concern for human rights.

Trade with China

China has gained increased attention recently as reports have surfaced of intense and widespread discrimination against the country’s Muslim ethnic minority of Uyghur people, who reside principally in a region called Xinjiang. They have long been the target of harassment by both the majority Han population and the Chinese government, but the situation has worsened according to a representative of the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, under President Xi Jinping, the region has been turned into “something that resembles a massive internment camp […] a sort of ‘no rights zone'”.

More concerningly, there are reports of designated political re-education camps, where detainees are forced to swear loyalty to the President, shout Communist party slogans, and endure other methods aimed to “brainwash and assimilate”. The “crimes” met with this punishment encompass anything from attempted political resistance to “greetings…expressions of Muslim ethno-religious culture”. These camps, which the Chinese government has outright denied the existence of several times have also produced reports of torture and “enforced disappearances”.

During a visit to China last December, Trudeau stated that he had brought up Canada’s human rights concerns with Xi Jinping. Simply “bringing up” the issue of human rights violations at a planned dinner, however, is not enough. China remains Canada’s second largest trading partner, with over $85 bn of bilateral trade every year.

The Argument for Staying In

There are always economic arguments to be made for deals so lucrative. When former Prime Minister Stephen Harper faced backlash over the Saudi arms deal in 2015, just a year after it had been signed, he responded that he didn’t “think it makes any sense to pull a contract in a way that would only punish Canadian workers.” Harper, implying that occasional disapproving comments were enough to discourage the country from carrying out grave human rights violations, actively ignored the stark contrast between Canada’s foreign policy and its commitments to human rights.

In 2016, Canada’s former Foreign Affairs Minister, Stephane Dion, stated that if this same contract were canceled, “there would probably be stiff penalties that Canadian taxpayers would have to pay”, and that the action would have weakened the government’s credibility when it came to other contracts. His spokesman, Joseph Pickerill added that “Saudi Arabia is a strategic partner and deals such as this have been agreed over successive governments”.

This is where the question of priorities becomes most important. The government undoubtedly has the right to make the choices that it thinks best for Canada, and human rights treaties signed at the UN are by no means binding. Furthermore, if domestic economic well-being achieved through unrestricted trade is this government’s priority, it makes sense not to threaten trade partners with sanctions should they fail to comply with Canadian or international human rights standards.

However, it is important to recognize that these are duties and expectations that Canada has imposed upon itself through signing international commitments, making rights-based promises to marginalized groups, and promoting itself as a global advocate for human rights. Despite the potential of “stiff penalties” and damaged diplomatic ties, Canada must choose between continuing to champion human rights on the world stage and reaping the benefits of unethical deals — it can’t do both.

Edited by Luca Brown