Canada’s Unique Private Sponsorship Program for Refugees: 40 Years Later

https://www.flickr.com/photos/13476480@N07/17444389323

https://www.flickr.com/photos/13476480@N07/17444389323

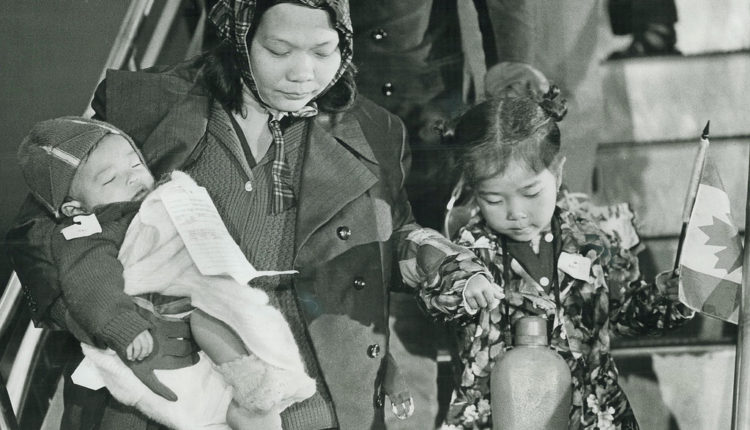

This year marks the 40th anniversary since the height of the refugee crisis that befell many South Vietnamese people and other minority groups in Vietnam. Those 40 years have seen other refugee crises come and go in many other countries, but the way in which Canada went about providing aid to those Southeast Asian refugees – the refugees included people from Laos, Cambodia, and of Chinese descent – stood out as unique and innovative. The way Canada handled the crisis in 1979 shaped their approach to resettling refugees for years afterward and has even now come to affect the way other countries are starting to approach refugee issues.

In the mid-1970s, the exodus of refugees from Vietnam began when forces from the north took the southern capital city of Saigon, causing many southerners to flee for fear of retaliation for their pro-United States contributions in the war that had just ended. Some of these original refugees made their way to Canada, but the crisis peaked in the late-1970s, as Vietnam struggled with ongoing divisions from the Vietnam War and a new regional conflict with China. The hostile situation in the country meant that many were forced to leave and seek asylum in neighbouring countries while other western nations scrambled to offer more permanent resettlement options. Canada presented itself as one of the main lifelines for those fearing the mistreatment that awaited the South Vietnamese who stayed. The mistreatment included loss of homes and property, labour camps, and restricted access to education and to employment.

What made Canada’s involvement in the Vietnamese refugee crisis noteworthy, though, is not that they took in many since others like the United States did so as well. Rather it is how they went about it since their approach was peculiar at the time, but it came to be pioneering. When this crisis began, refugee status as a distinct category for immigrants did not exist in Canada, but a new immigration act was introduced in 1978 which would properly define refugees, and thus ensure Canada could fulfill its international obligations toward refugees. This new Act also launched the program which would eventually be modelled in numerous other refugee programs in many other countries: the private sponsorship program.

Canada was the first country to implement a refugee sponsorship program of the sort. The Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program allowed community organizations, ethnic groups, families, and others to sponsor refugees coming to Canada, a program which in 1979 meant that public sympathy for the plight of Vietnamese refugees could be translated into direct support. According to the program, the Canadian government would sponsor one refugee for every refugee sponsored privately. The program has since been adapted where sponsors fund the first year of resettlement while the government covers education and health costs. In the second year, the refugees are eligible for government social welfare benefits. Broadly speaking, the program allows Canada to provide aid to more refugees than it otherwise would have been able to.

Before the program had been tested, the international community was facing a challenge to alleviate the expanding pressure on the intermediate camps only designed to be temporary, and with the swell of refugees from Southeast Asia continuing to grow, Canadian officials announced their intention to accept 60,000 refugees by 1980. This commitment was possible in large part because of their private sponsorship program. Of the 60,000 refugees accepted in Canada, less than half were sponsored by the government, while the resettlement of the other 34,000 was made possible through the financial support of the private sector and family members already living in Canada. Across Canada, local community and religious groups came together to raise funds and sponsor as many Vietnamese families as they could, to the point where by 1985 Canada had resettled over 100,000 Vietnamese refugees.

The program began with the intention of accommodating more Vietnamese refugees, however, in the 40 years since Canada started accepting refugees through its private sponsorship program, many others have benefitted. Since 1978, Canadian university students have enabled 1,400 refugees to study in Canada through their fundraising efforts. As a result of the violence and internal tensions within Iraq during the American invasion and occupation in the 2000s, thousands of refugees came to Canada through sponsorship. Between 2003 and 2018, Canada welcomed over 37,000 Iraqi refugees. In response to the Syrian civil war, Canada accepted almost 40,000 refugees, of which 45 percent were at least in part privately sponsored. Since its implementation, the program has enabled Canadian citizens to directly engage in the resettlement of refugees and has often allowed Canada to offer more humanitarian assistance than it otherwise would have been able to.

As mentioned, Canada was the first to try this approach, where private citizens could be so directly involved in the process of resettling refugees. For its role in helping the refugee crisis in 1979 through the private sponsorship program, Canada was awarded the Nansen Medal by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in 1986, recognizing its contribution to refugee protection. The program has also been successful enough in the time since the Southeast Asian refugee crisis for it to influence immigration policy in other countries. In 2016, Canada pledged to export the model, and Britain and Australia have since undertaken steps toward new private sponsorship schemes. Following Canada’s response to the Syrian refugee crisis, they received inquiries from a dozen other countries concerning their sponsorship program, showing that the program – which began with the crisis in 1979 – has allowed Canada to remain a leader internationally now years later.

While the program has garnered international recognition, it remains imperfect. New restrictions limit the number of refugees who can be privately sponsored, but when the willingness to sponsor refugees is still strong in many communities, capping the amount of aid seems rather inefficient. Moreover, while not a shortcoming necessarily characteristic of the program, in the Canadian case there is a significant backlog of sponsor applications which could directly translate to aid if they were processed more effectively. There are also concerns that the work of sponsoring refugees has fallen onto a small number of individuals and organizations who are heavily relied upon for the program to succeed.

More recently, asylums seekers and refugees have been depicted by many as terrorists and as cheats trying to take advantage of the system, and the administrative process for sponsoring refugees is getting longer. In a political climate like our present one where immigration – even if it concerns refugees – has become such a contentious topic, the merits of a policy that relies heavily on the support of individuals warrant a second look. So far though, the resettlement of refugees remains relatively popular among Canadians, as shown by the most recent Syrian refugee case where the number of private citizens seeking refugees to sponsor exceeded the number of refugees coming to Canada. While the program has its obstacles and shortcomings like any other immigration plan, it remains true that the approach thus far has been beneficial to many disadvantaged communities, giving another chance to those fleeing sometimes horrific conditions, who otherwise may not have had the opportunity to come to Canada.

If public support for the program remains high in Canada, not only will Canada continue to set an example internationally, but its only obstacle to providing lasting and continual humanitarian relief will be the arbitrary restrictions placed on the number of refugees coming to Canada on a yearly basis.

Edited by Pauline Werner