A Century of Humiliation: Understanding the Chinese Mindset

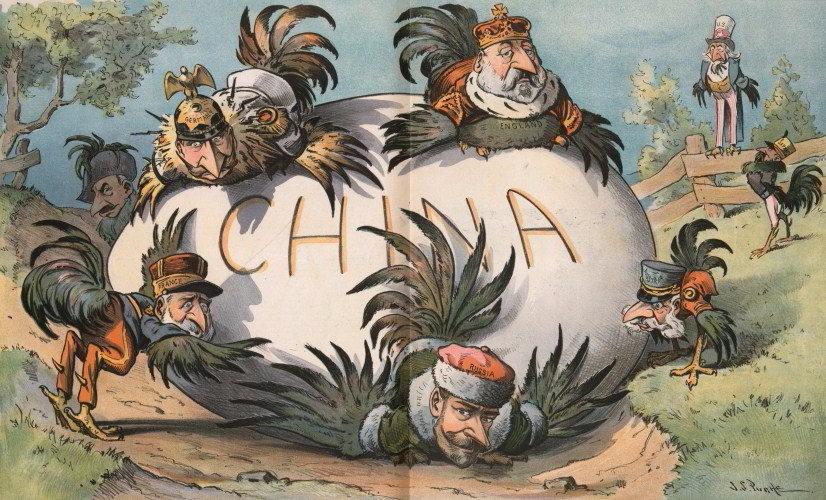

A Troublesome Egg to Hatch by J.S. Pughe: Retrieved http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010651397/

A Troublesome Egg to Hatch by J.S. Pughe: Retrieved http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010651397/

The CCP’s Narrative:

In 2017, Xi Jinping addressed the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, extolling Ancient China as a once great nation “plunged into the darkness of domestic turmoil and foreign aggression; its people were ravaged by wars, saw their homeland torn, and lived in poverty and despair”. The era he describes is known by the Chinese as the Century of Humiliation, which began on August 29th, 1842 upon China’s defeat to the British Empire at the close of the First Opium War. This ceded Hong Kong to the British and forced open five treaty ports to international trade. The Century of Humiliation ended in 1949 with the seizure of power by the Chinese Communist Party under the auspices of Mao Zedong.

The ensuing century scarred the Chinese psyche, whose prestige as the Celestial Empire was damaged by a series of brutal invasions by the era’s Great Powers. Great Britain, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, and the United States of America all vied for a chunk of the Chinese empire; China lost 1/3 of its territory and tens of millions Chinese perished. The Chinese suffered 35 million casualties during WWII, and were the first to fight in 1937 against Japanese expansionist aggression. In addition, the propagation of Christianity into China was partly responsible for the brutal Taiping rebellion in 1850 by Hong Xiuquan, who claimed to be the younger brother of Jesus Christ and launched a brutal revolt against the ruling Qing dynasty; even modest estimates place the death toll around 20 million.

The West has mostly forgotten about these events, with the Opium Wars relegated as a brief footnote in history. However, to understand modern China requires an analysis of its Century of Humiliation to grasp the motivations of the CCP. This century of malaise began on a fateful day: November 3rd, 1839.

First Opium War:

British merchants were desperate because a grave trade imbalance existed between Qing Dynasty China and Great Britain due to the latter’s high demand for tea, porcelain, and silk; demand for tea amounted to over 23 million pounds in 1800. The issue was compounded by the Qing’s Canton system that restricted foreign trade to the port city of Canton where the Qing demanded all exports be paid in silver, leading to an annual tab of 3.6 million pounds of silver. British manufacturers had little to offer China as the Qing emperor expressed to the British that “we possess all things. I set no value on objects strange or ingenious, and have no use for your country’s manufactures”. This forced British merchants to search for a viable alternative, one found in the highly illegal narcotic of opium.

The Canton system of trade was not an overtly protectionist measure, but rather was utilized by the Qing to incentivize foreign trade, as Canton was the only port with sufficient facilities required for foreign merchants. These facilities included warehouses storing goods from across China and sufficient capital to incentivize merchants to embark on their year-long trek across the globe. Furthermore, the myth of a restrictive Qing economy must be dispelled, as the Chinese state had adopted a laissez-faire approach to economic regulation since the 7th century under the Tang dynasty because state capacity was unable to maintain control over the territorial breadth of China. Significant factors contributing to Chinese economic growth of the era materialized not through state-regulated economic activity, but rather “by the dynamics of the dominant private sector of the economy”.

Qing China’s economy existed on a continental scale, accounting for 1/3 of the world’s GDP, with a population of 450 million, and economic integration via the removal of all barriers to intra-empire trade and investment in great public works such as the Grand Canal linking Southern and Northern China.

The Qing did not require British goods; British demand for tea and growing trade imbalance forced merchants to deal with Opium. The British Empire thus became the greatest drug cartel of the era. Rampant opium use in China (which was illegal under Chinese law) forced the Qing court to act as more flowed into China every year. Therefore, in 1839 the Qing court requested that the young Queen Victoria cease her empire’s sinful trade and seized 3 millions tons of opium stored by British merchants at Canton.

Britain declared war, and by 1842 had cut the Grand Canal in two through the seizure of Zhenjiang, paralyzing the government’s tax barges, transport, and ability to administer their vast empire. The British were aided by the advent of superior ships, weapons, and tactics after decades of colonial conflicts.

The Qing were forced to surrender and the British dictated terms; Hong Kong was ceded to the British, treaty ports opened to the British and facilitated access of opium into China, and Britain gained most favoured nation status, granting it economic privileges its competitors did not possess. This was the first blow against China, to be followed by the Second Opium War against the French, British, and Americans, which would culminate in the razing of the Chinese Summer Palace. A British soldier remarked, “When we first entered the gardens they reminded one of those magic grounds described in fairy tales; we marched from them upon the 19th October, leaving them a dreary waste of ruined nothings”. French writer Victor Hugo solemnly regretted the deed, writing, “We call ourselves civilised and them barbarians […] Here is what Civilisation has done to Barbarity”.

The Chinese Psyche:

The burning of the Summer Palace is described by some as China’s Ground Zero. The CCP encourages patriotic visits by Chinese school children to remind them of Western aggression, with the dominant narrative being that only a strong CCP can prevent another calamity.

Chinese policymakers learned the danger of being caught off guard and viewed the world as filled with robber barons who sought to take advantage of China’s weakness to enrich themselves. As late as 2004, Chinese General Secretary Hu Jintao told the Peoples Liberation’s Army (PLA), “Western hostile forces have not yet given up the wild ambition of trying to subjugate us”. This sentiment is echoed by PLA publications portraying Western nations as aggressive and greedy, owing to their historical roots as “slave states that frequently launched wars of conquest and pillage to expand their territories, plunder wealth, and extend their sphere of influence”.

China learned from the conflict that it had fallen behind, as the explicit goal of all Chinese governments since has been an emphasis on modernization and industrialization. China is now a premier global power, seeking to reclaim its status as the foremost global power, and in doing so is embarking on significant maritime expansion. It has stringent laws regarding narcotics, with 470 executions due to drug-related charges in 2007 alone, after its experience with opium; its harsh anti-narcotics laws involve drug penalties to mid-level traffickers.

As China and its international presence grow, greater insight into how China views the world is needed, as while the West may have forgotten the Opium wars and the burning of the Summer Palace, China, especially the CCP, has not. The Chinese exhibition Road to Revival recounts the Century of Humiliation, starting first with the Opium War and ending with the Communist Party’s victory in China. Nuclear missiles are on prominent display at its end and its implicit message is clear; China is back, don’t mess with us again.