Child Soldiers around the World: Can You Relate?

Over my short lifetime, I have lived in and travelled to over 28 countries. My family and I have moved numerous times, mainly due to my dad’s work, which has taken us everywhere around the world. During our travels, we spent four years in Guinea from 1994 to 1998. Our stay there coincided with an ongoing civil war in our neighboring country, Sierra Leone, which started in 1991 and only ended in 2002. [1] We lived in a port village, right on the coast, called Kamsar. I have few memories of that time, since I was merely five years old. However, I do remember the people in our village and the stories they told.

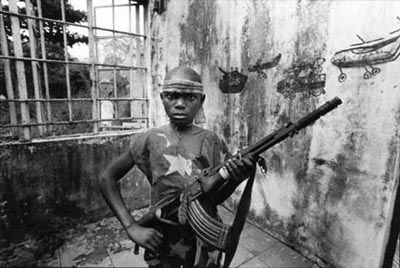

I was inspired to write this article on child soldiers, after having known a refugee from Sierra Leone, who was sheltered by my family in Guinea. My parents have often told me the story of our cook, Ansou, and how he escaped the Sierra Leone civil war. He arrived at our door one day pleading for work. Ansou did not have any family members left, which made it easier to escape his country and find refuge in a neighboring one. He would recount horrific stories of the war, and one of the most striking memories he described was about seeing large numbers of children wandering the streets. He thought these roaming kids were lost or abandoned, but he quickly realized they were carrying guns.

To think that children, who were the same age as I was when we were living in Guinea, were part of the  armed forces is gut wrenching. Children accounted for almost 80% of all soldiers in the Sierra Leone civil war [2]. They were abducted from their families, often raped, and forced to kill innocent civilians. These child soldiers were on average 11 years old and spent about 4.7 years enslaved in the army [3]. There are two reasons why training children is easier than training adults: they have a limited ability to assess feelings of vulnerability, risks, and shortsightedness, and they are far less expensive. In addition, children are less experienced and therefore are easier to convince. The younger and longer a child remains part of the military division, the more he or she forgets his family and reality. [4] This forgetfulness of loved ones and loss of reality brings about a feeling of ownership and camaraderie with the armed group. The children believe the violent rebels are their family and there is nothing left of the outside world – that is when it becomes dangerous and these confused youngsters turn into killers.

armed forces is gut wrenching. Children accounted for almost 80% of all soldiers in the Sierra Leone civil war [2]. They were abducted from their families, often raped, and forced to kill innocent civilians. These child soldiers were on average 11 years old and spent about 4.7 years enslaved in the army [3]. There are two reasons why training children is easier than training adults: they have a limited ability to assess feelings of vulnerability, risks, and shortsightedness, and they are far less expensive. In addition, children are less experienced and therefore are easier to convince. The younger and longer a child remains part of the military division, the more he or she forgets his family and reality. [4] This forgetfulness of loved ones and loss of reality brings about a feeling of ownership and camaraderie with the armed group. The children believe the violent rebels are their family and there is nothing left of the outside world – that is when it becomes dangerous and these confused youngsters turn into killers.

An important question to address is whether these child soldiers will ever return home, and if so, how will they ever transition back to a normal life? In order to make a smooth and successful change, there are four ways families and communities can aid the children back into their society. The first method focuses on the family. “Acceptance from family members and friends has been indicated as an important post conflict determinant of psychosocial adjustment.” [5] By having a welcoming and accepting family, the children will have an easier time adapting to their original life, without feeling guilty or sorrowful about their past.

Acceptance from the local community is the second technique. Similar to the family situation, it is not easy for the community to accept an ex-killer into their midst. They know what the child must have done, but they also realize the child had no choice in the matter. If the neighborhood accepts the child back into the village, it will encourage the child to restore the life they had once lost. Furthermore, the community has the manpower and capacity to set up care units that can help the free soldiers with their difficult transition [6].

Education is important on so many levels, including this one. As the third approach to easing the child soldiers’ path to normalcy, education is essential for a child’s reintegration into the community: it builds confidence and self-esteem, in addition to providing extra-curricular activities and school outings. [7] Being in school enables these released soldiers to think about things that are unrelated to war and violence – it takes their mind off of the awful acts they committed while taking part in the armed forces. Opportunities for learning and developing literacy skills have shown to act as a damper on the likelihood of re-recruitment. In addition, they aid former child soldiers in adapting to a new life.

Education is important on so many levels, including this one. As the third approach to easing the child soldiers’ path to normalcy, education is essential for a child’s reintegration into the community: it builds confidence and self-esteem, in addition to providing extra-curricular activities and school outings. [7] Being in school enables these released soldiers to think about things that are unrelated to war and violence – it takes their mind off of the awful acts they committed while taking part in the armed forces. Opportunities for learning and developing literacy skills have shown to act as a damper on the likelihood of re-recruitment. In addition, they aid former child soldiers in adapting to a new life.

The fourth and most important solution is the implementation of specific programs for the returning children. An example would be the Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) program, which was established in Sierra Leone. [8] These programs include small steps that the released soldiers can follow. Some of these steps include finding their families, leaving their weapons, returning to school, as well as doing some familiar activities, such as going to church or going to a playground.

In 2007, there were approximately over 250,000 children actively participating in armed forces all across the world, according to UNICEF. [9] In 2012, this number rose to 300,000 children. [10] As I think back to my time in Guinea, it is hard to imagine what kind of life these child solders had: they were forcefully kidnapped from their homes, compelled to kill and to take different drugs. It’s inconceivable to think that there are still thousands of soldiers around the globe who are only children.

Photo courtesy: Creative Commons Flickr

Bibliography

[1] Martz, Erin. “Chapter 14.” In Trauma Rehabilitation after War and Conflict: Community and Individual Perspectives, 311-349. New York: Springer, 2010.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Betancourt, Theresa. “Sierra Leone’s Former Child Soldiers: A Follow-Up Study of Psychosocial Adjustment and Community Reintegration.” Child Development 81, no. 4 (2010): 1077-095.

[4] Martz. 2010.

[5] Betancourt. 2010. P. 1085.

[6] Maclure, Richard, and Myriam Denov. “‘‘I Didn’t Want to Die So I Joined Them’’: Structuration and the Process of Becoming Boy Soldiers in Sierra Leone.” Terrorism and Political Violence 18, no. 1 (2006): 119-35.

[7] Hill, Kari. “Rehabilitation Programs for African Child Soldiers.” Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice 15, no. 3 (2003): 279-85.

[8] Betancourt. 2010. P. 1090.

[9] “Child Protection.” UNICEF. N.p., Apr. 2007. http://www.unicef.org/media/media_35903.html.

[10] Chatterjee, Siddharth. “For Child Soldiers, Every Day Is A Living Nightmare.” Forbes, Dec. 2012. http://www.forbes.com/sites/realspin/2012/12/09/for-child-soldiers-every-day-is-a-living-nightmare/#786a3d62603e