China Under the Spotlight: How the 2022 Winter Olympics Showcase More Than They Intend

On Friday, Feb. 4, Chinese President Xi Jinping opened the Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, inaugurating the country’s first-ever Winter Olympics and the city’s second games in 14 years. Despite the reduced capacity and other COVID-19 precautions, the opening ceremony went without a hitch. Beyond the pomp and the smiles, however, underlies a roiling diplomatic dispute over the Games. Countries like Canada and the United States have expressed their discontent at China hosting the games. This comes amid increasing awareness of the country’s human rights abuses against the ethnic Uyghur minority, the continued repression of pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong, and other signs of the country’s growing confidence in its authoritarianism.

Much has changed for China since the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics. Whereas those Olympics were a statement of China’s arrival as a significant player on the world stage, the country has now firmly established itself as the United States’ main international challenger. So why did China want to host the Games again? International sporting competitions such as the Olympics have often served as a significant propaganda opportunity and, therefore, an irresistible draw for an authoritarian government obsessed with its public image. The last three winter Games have drawn in more than 1.8 billion viewers. Thus, China hoped to use the Games to promote its political agenda — which was also its main goal in 2008 — by showcasing a carefully curated spectacle over the two weeks of competition to both a domestic and international audience.

This curated spectacle was front-and-centre during the ski and snowboard competitions. The cameras zoomed in, depicting pristine, snowy slopes suited for the athletes’ effortless runs and mind-bending twists and flips, just as China intended. But zoomed out, they reveal a stark contrast with the landscape: brown, barren mountains surrounded the bright snowy Olympic venue. The Zhangjiakou and Yanqing districts that host the action do not have enough naturally-occurring snow for competition. The Beijing region, which Zhangjiakou and Yanqing are both a part of, receives an average of just 6 mm of precipitation in February (compared to 66 mm here in Quebec). Undeterred, China invested 76 million dollars in producing artificial snow despite negative environmental impacts such as the effects on vegetation growth.

Even before these environmental repercussions, China — and the Beijing region — was struggling with a water crisis; the Yellow River had become so polluted that it no longer supplies drinking water. The government has had to disrupt the natural water cycle and relocate an unknown number of residents to acquire the necessary 222 million litres to make snow. This demonstrates how nothing — not even local populations or environmental conditions — will stop Beijing from creating a show that meets its ambitions.

The well-curated images of the Beijing Olympic ski courses provide a fitting metaphor for the larger, socio-political dimension of these Games. They present the quintessential exhibit of good, clean, harmless excitement from up close. But look beyond Beijing’s closely-cropped image, and the persisting consequences of China’s authoritarianism reveal themselves. The greatest of these concerns are the human rights abuses of the Uyghurs in the Western state of Xinjiang. As recent reports have uncovered, China has been forcefully detaining up to 2 million Uyghurs — a Muslim minority — since 2014, forcing them to abandon their native language and culture to assimilate in so-called re-education camps and separating children from their families. The treatment of the Uyghurs demonstrates an unscrupulous attempt by Xi Jinping’s government to destroy the Uyghur culture and language to create a more loyal and homogenous Chinese population — an action that Canada and the US have labelled a ‘genocide.’ In response to China’s ongoing human rights abuses, Canada, the US, and other democracies like Japan and the UK have staged diplomatic boycotts, a toothless half-measure that China’s foreign ministry dismissed as a “farce.”

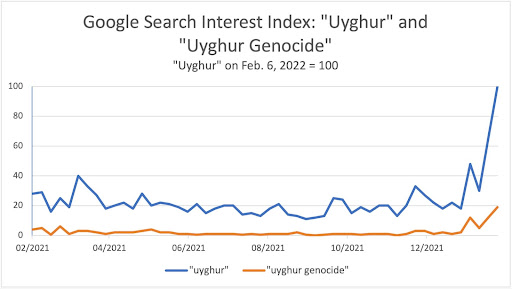

Though China might have hoped that the Olympics would distract from these ongoing issues, that strategy — at least for now — seems to have backfired. As Google search trends reveal, the terms “Uyghur” and “Uyghur genocide” have skyrocketed — an almost five-fold increase relative to pre-Olympics numbers — at the start of the Games. A surge in media presence, such as the Olympic articles on the New York Times front page, including caveats about China’s human rights record, backed up the online search interest and worldwide protests condemning China’s human rights abuses. In this way, while attempting to stage a distraction, the Beijing Olympics have brought even greater international attention to the Uyghurs’ plight.

The host nation’s decision that little-known cross-country skier Dinigeer Yilamujiang, an Uyghur, was to light the Olympic flame seemed like an attempt to portray national unity, but the gesture phased few outside of China. If anything, it might have generated even greater awareness of China’s inhumane treatment of its Muslim minority. But all this fuss matters little to China itself. Within the country’s borders, Yilamujiang’s appearance was praised for depicting the depth of Chinese culture and unity. For Xi, criticism of his human rights record is of little consequence. Given his party’s economic and political might, he can afford to ignore international outcry while staying his course in Xinjiang.

Meanwhile, Xi is primarily concerned with his power at home and abroad. These Olympics are a chance for Xi and his party to drum up nationalism, as a unified and obedient population is essential to his Communist party’s hold on power. As the party demonstrates time and time again, it will use any means necessary to stifle attempts at civil disobedience, from the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre to the ongoing crackdown on Hong Kong pro-democracy protesters. At the same time, the government placates its people both through patriotic displays and through athletic achievement, which it has been keenly cultivating in recent years despite its absence of a winter sports culture. Already China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong, Xi has used Beijing 2022 as a victory lap.

Internationally, these Games effectively advertise the so-called “China Model” — a Sino-centric and authoritarian mix of socialism and capitalism — as a more efficient alternative to the democratic American model. The massive initiatives undertaken at the expense of local populations are the reason for its appeal. In short: China gets things done quickly, efficiently and bulldozes any obstacles in its way, as the new Olympic ski slopes and high-speed train demonstrate. This ruthless and proven efficiency is a significant draw for developing nations with poor infrastructure, which might find China’s Belt and Road initiative more effective than the neoliberal “Washington Consensus.” Beijing 2022 is China’s flashy pitch to the world for its economic and political model.

These Olympics showcase the best of athletics and reveal the worst in human rights. But amidst the festivities and protests, Xi has increased his domestic power and advertised his international model. For Xi and his party, the diplomatic outcry over these Games is second to their domestic reception. Indeed, the same images that we might interpret negatively are the very reasons for its appeal to the Chinese government — a sign that China has organized these Olympics on its own terms and for its own gain.

Edited by Pascal Hogue & Teresa Tolo

Featured image “Heads of state, including Chinese President Xi Jinping (centre), pose for a photo at the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics.” by Casa Rosada is licensed under CC BY 2.5 AR.