A City More Divided—The United Jerusalem Bill

As the epicentre of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Jerusalem serves as more than the Holy Land over which believers of the Abrahamic religions fight. After President Donald J. Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel on December 6, 2017, the Knesset approved the United Jerusalem Bill which strengthened the Israeli hold over the city.

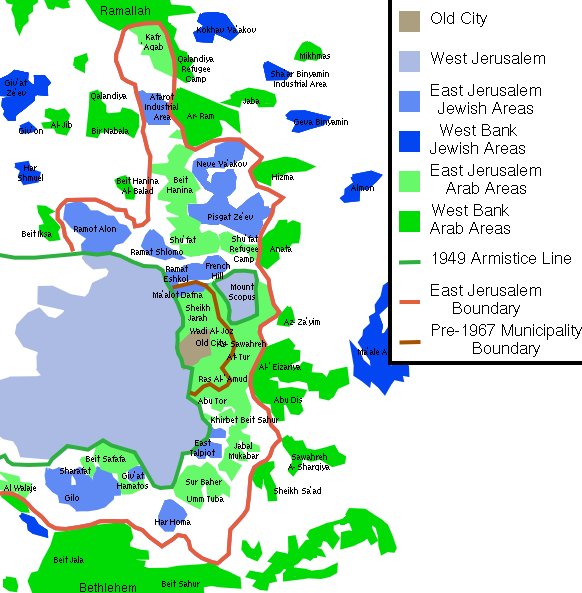

Jerusalem is long-divided. Since the age of the Crusaders, the Holy Land has been divided along religious and political lines. In the aftermath of the Arab-Israeli War of 1948 , Jerusalem was separated along the the lines of the Old City. Israel took control of an area which later became West Jerusalem, and Jordan claimed East Jerusalem. Since the day Israel declared statehood, modern Jerusalem has stood as a divided territory. Two decades later, in the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel annexed Mount Scopus, the Old City, and other neighborhoods within the Arab sector, violating United Nations’ partitioning of Jerusalem.

Throughout the following decades, there is a growing presence of Jews in East Jerusalem neighborhoods. Some moved in for ideological belief that the whole Jerusalem is part of ancient Israel; some moved in for increasing economic subsidies from the government to escape the overcrowded downtown area. While Jews migrate into East Jerusalem for various reasons, the Knesset put effort into establishing difference between Jewish and Arabic neighborhoods. Jewish neighbourhoods tend to have cleaner environment, more convenient access to public service, and more organized housing area. On the contrary, Arabic neighborhoods look undeveloped. Aside from physical divisions of boundaries, the Israeli government used rhetorics of civic security and societal stability to enact bills that are, in their essence, discriminatory toward Arabic inhabitants. The gap between Arabic and Jewish communities only increased gradually since 1948, and the United Jerusalem Bill, sixty years from the day of division, is an epitome of how Israeli-Palestinian division has not moved forward in the past half of the century, but one of the many controversial and effortless actions to maintain Jewish dominance of the Holy City instead of resolving the draining conflict.

The discriminatory treatments shone through in several aspects. Legislatively, according to the Israeli Supreme Court’s Recognition of East Jerusalem as an integral part of Jerusalem, residents from East Jerusalem neighborhoods are under Israel laws in which they should be automatically Israeli citizens. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court has revoked the residential status of almost 15,000 Palestinians between 1967 and 2017, leaving these people fall short of citizenship, thus, unable to enjoy the welfare and benefits from the government. The Israeli government has been criticized for this hypocritical decision–is there a genuine desire from the leaders to solve the lasting conflict. Palestinians in Jerusalem struggle with their legal identities and their mobility is limited due to a lack of citizenship or as a secondary citizenship. While the government attempts to settle ethnic tensions, the legal divisions between groups have inhibited resolution. Palestinians in Jerusalem have been long exhausted by the endless procedure of acquiring citizenship. How can a city be united when its residents are in various classes?

In addition, the Jerusalem Municipality does not provide public service in these neighborhoods, including trash collection, public education, or policing.

These different treatments create unpleasant living conditions for the Arab residents, leaving them in an awkward position between the Municipality of Jerusalem and their Arab identity. Some East Jerusalem neighborhoods refuse service from the Municipality and turn to the Palestinian Authority for help. Nevertheless, because the neighborhoods are legally under the regulation of the Municipality, the Palestinian Authority use this as a reason for not supporting East Jerusalem but condemn the Israeli government for not exercising their legal promises of citizenship, public service, and welfare for its Arabic residents. For instance, the Shu’fat refugee camp located in East Jerusalem suffers from degrading living conditions due to lack to policing and public service. Approximately 80,000 people live in Shuafat and surrounding neighborhoods where they suffer from overcrowded living areas and lack of mobility. Odor of refuse pile up in every corner, roads are poorly constructed, and health clinics barely exists. The PA neither help to improve the living conditions. Claiming that the camp is under Jerusalem Municipality, the PA exists as a vague ideological figure who calls for resistance when necessary. 76% of the residents still live below poverty line.

Restricted mobility and worsening living conditions create psychological imbalance for the residents–why do residents under the regulation of the Jerusalem Municipality, who pay taxes, live such different lives compared to their West Jerusalem counterparts. The physical checkpoints and the constant denial of service requests and citizenship applications are forms of rejection from the state of Israel by emphasizing Arabs as separate identities in the society. They are not Jews, therefore they should not automatically acquire citizenship even though they live within the borders of Israel. They are dangerous, therefore they should pass checkpoints to enter downtown area. They are different, therefore they should be separated. The physical separation checkpoints or fences only reinforce the notion that the Jews and the Arabs cannot come together.

While Jerusalem continues to divide along geographical, religious, and political lines, the newly approved United Jerusalem Bill has rendered the division even further. The bill, pushed by the Jewish Home Party Chairman Naftali Bennett, is an amendment to Israeli Basic Law about Jerusalem to ensure that the city is never divided. The new bill stipulates that “a majority of 80 Knesset members will be required to change the status of Jerusalem or for any transfer of territories from the capital within the framework of a future diplomatic agreement” in which previously 61 votes will be sufficient. The bill further strengthens Israeli claim of Jerusalem as its own capital, making East Jerusalem and other Israeli occupied settlement harder to detach. It is a slap on the face of the Palestinian Authority, who recently seems to move closer to negotiation with the gradual realignment of Fatah and Hamas.

While the bill does nothing to strengthen support or to provide service for its Palestinian residents, it essentially allows the exclusion of Arab residents from Jerusalem. The legislation seeks to remove Palestinian neighbourhoods from the jurisdiction of the current Jerusalem municipality, affecting the Shu’fat refugee camp and the Kufr Aqab neighbourhood already on the other side of the separation wall. Israeli legislator Esawi Freige said during the vote on the bill that “the new Jerusalem law is a race law; it’s a law meant to cleanse Jerusalem of its Arab residents.” Supporters of the bill argue that the bill is a combat toward the growing demographic challenge of overpopulation by building new Jewish neighborhoods by expanding current territories, yet the bill eventually marginalize its Arabic population.

While Palestinians leaders seek East Jerusalem as the capital of a future state, Israel says Jerusalem is indivisible. The city itself has been long divided, and the new bill prompted widespread condemnation and protests from both the Palestinian territories and around the world. Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas said that the approval of the United Jerusalem Bill has “killed the peace process” and “initiated war on the Palestinian people.” The new bill makes negotiation and the two state solution more obstruent. It has not united the city but escalates the conflict. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is entering a new age.

Edited by Kathryn Schmidt