Closing the Gap: Indigenous Injustice Parallels in Australia and Canada

It’s strange that the country ranked second-best in the world for quality of life is, at the same time, becoming infamous for the justice gap between its non-Indigenous and Indigenous populations. Life for Australia’s Indigenous peoples is far from the world’s second-best; widespread gaps exist across domains like education, health, and security.

On 26 October, the Australian government rejected a referendum proposal, named the Uluru statement, to form a body for Indigenous voice in parliament. This is especially concerning since it not only silences any discussion towards successful reconciliation and policy changes, but also shows an alarming restriction on the country’s public debate and participation.

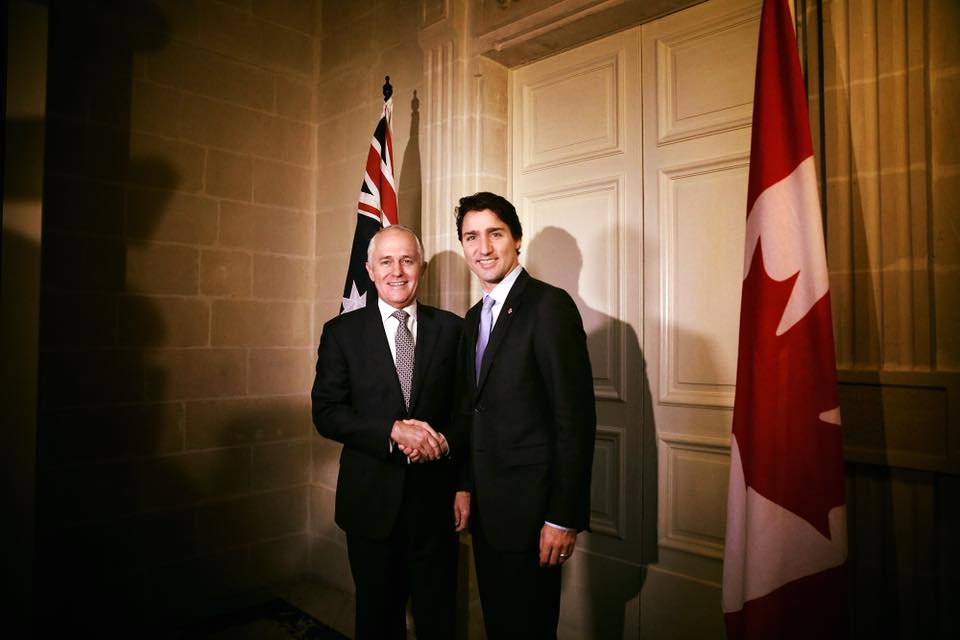

Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion claimed to have refused looking into to proposal further under the premise that the Australian public would never have supported it, and that its success would be highly unlikely. There was also a fear that a constitutionalized Indigenous voice to advise lawmakers would create a “third chamber” in Parliament.

Contradictory to these claims, results from a new survey study have showed that over 60% of respondents are in favour of the changes. Prominent lawyers, referendum council members, and senators have also come forward with criticisms that explain how the view of the “third chamber” is misleading for the Australian public, and only exacerbates the stagnant situation for reforms. They emphasized the Prime Minister’s deliberate misinformation of the public, and labelled political tension as a main cause for the government’s inability to undergo a proper legal and political analysis before the decision was made.

This is not the first instance that the Australian government has taken a backward move in its Indigenous affairs. To date, it is the only Commonwealth state in which no treaty has been signed with its Indigenous population, prolonging the 200-year cycle of the federal government’s intransigence with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

The government’s primary strategy for tackling the disparity is Closing the Gap: a formal commitment monitored by the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) to achieve health equality by the year 2030. Targets include reducing child mortality, increasing literacy and access to education, increasing employment, and prolonging life expectancy.

Progress on this strategy has been meager. The lack of success in improving health, education, and employment has led to distressing rates of child incarceration and violence against women. Further, the UN has described it as unacceptable that, despite two years of economic growth, Australia still has not managed to mitigate the social disadvantages of the Indigenous peoples.

A fundamental factor enforcing the cycle of missed targets is the lack of coordination among all levels of government and Indigenous leaders. Without appropriate representation and power, it’s difficult to make federal or municipal officials develop methods for carrying out the strategy in a community-driven way; the Indigenous communities are the ones facing the outcomes of any strategy. This is crucial for preserving both their identity and well-being.

Another important factor includes inadequacies in media attention – news outlets typically do not interest themselves with minute policy changes, especially relating to Indigenous affairs. While this is understandable as a selling tactic for any issue, there has been less emphasis on the context of native news overall and more on highlighting the pessimistic statistics. For the public to hold its decision-makers accountable for the near stagnant progress on Closing the Gap, there needs to be a strong scope of information available. Of course, the education system also plays a significant role in this.

These fallbacks are not unlike those of the Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Its 94 ‘calls to action’ were clear and concise but insufficient in their enforcement and ability to evoke policy change. Indigenous communities in Canada continue to face impoverishment, inadequate housing, poor health, food insecurity, and unsafe drinking water. Not to mention, the country initially voted against the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Vital projects such as social assistance and housing infrastructure continue to be underfunded, which have led to the heightened rates of crime and substance abuse. In Canada, the intergenerational trauma from residential schools affects crime rates as well. Much of the resource development has also taken place without the proper consent of the First Nations’ whose land is concerned. Take the construction of the Site-C dam in British Columbia for example; the only way for the Indigenous peoples to object to projects like these is through long and costly litigation, which should not be the case.

Most recently, on November 3, the Canadian Supreme Court approved a proposal to build a ski resort on land considered sacred for the Ktunaxa Indigenous community in BC. This was a blow to both the community’s religious freedom, and again the country’s apparent progress in recognizing its historical mistreatment of such groups.

Over the years, Canada has moved slowly in ameliorating its gap between non-Indigenous and Indigenous populations. It’s becoming more and more acknowledged that the country’s racism and colonialism towards Indigenous groups in history still somewhat exists today, from human rights campaigns to politicians’ statements. The increasing discussion and level of understanding arising is an immense and necessary accomplishment, but not a sufficient one.

The case of missing and murdered Indigenous women depicts this perfectly; after much effort from lobbyists, public outcry, and Indigenous groups themselves, the government finally agreed to launch a national inquiry in September of last year. Advances have been little, as the conflicted process faces the absence of organized structure, long term commission plans, and public reports.

Unlike Australia, there are in fact a number of treaties and agreements binding the Canadian government and Indigenous peoples. Nonetheless, the degree to which these treaties have been upheld is below par, as previously described with land violations.

Why have some of the most developed and liberal countries been so ineffective and untimely in their efforts to fix injustices to their Indigenous peoples? A key idea to enforce is that “reconciliation is more than words, it’s action”. The leaders who have the power to incite action are often too dismissive or “stalling” of actual Indigenous interests, applying a slightly paternalistic approach to work that should include the main stakeholders themselves.

It says a lot about the two states in question when their strategies have not only been unsuccessful in reducing gaps in equality, but more importantly have failed to include and take into account Indigenous opinion and advice. Indigenous voices are also the voices of the public. When these voices are repressed, it is indicative of strain on national freedom. Achieving complete reconciliation will continue to be an exacting process, but when achieved, it will benefit not only Indigenous peoples but Australia as a whole; making it a global norm for others to follow.

Edited by Luca Loggia