Common-Wealth of Reform: Looking Abroad to fix Canada’s Electoral System

https://flic.kr/p/9R6hoz

https://flic.kr/p/9R6hoz

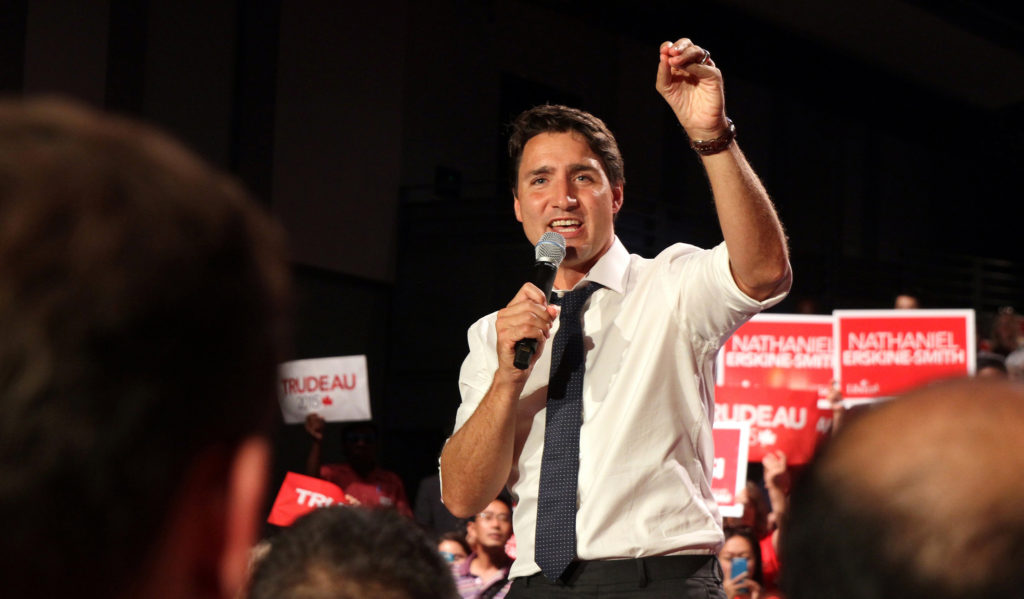

With the passing of the New Year, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his government have entered their third full year in power. Elected on a platform promising progressive reform, Trudeau was quick to act on certain campaign promises that would alter the machinery of government. One of Trudeau’s first acts as Prime Minister, for example, was to implement the first gender-balanced Cabinet in Canadian history, setting a precedent for future governments. The election of the Liberal government also ensured the scrapping of the Citizen Voting Act, a proposed bill that would have limited the voting rights of Canadian expats. Furthermore, the Liberals have tried their hand at Senate reform, creating a non-partisan advisory board to select new Senators. This has been a major departure from the previously-established convention, by which Senators were chosen at the Prime Minister’s pleasure. This had historically lent the body to both partisanship and patronage, albeit being styled as a “sober second thought” on legislation introduced to the House of Commons.

In terms of equity and representation, Trudeau’s reforms have been a step in the right direction. However, the Liberals have fallen flat on some of their more ambitious promises. Although it was promised that the 2015 election would be the last to utilize first-past-the-post voting, efforts to adopt a more accurate and fair method came to a grinding halt in early 2017. The Government was met with harsh criticism from the opposition, particularly the New Democrats and Greens, parties that would have most likely gained the most from electoral reform. Likewise, the Conservatives accused the Trudeau government of deceiving Canadians on one of their major campaign promises. The Liberal government would cite the inability to form a consensus amongst parties and Canadians as the main reason for the failure of electoral reform.

Canada does not stand alone in the world in facing the challenge of electoral reform. With its government structures based heavily on the Westminster parliamentary system, Canada shares a great deal in common with many former British Colonies as well as the United Kingdom itself. More so, as former British Dominions and contemporary Commonwealth Realms, no two former colonies share government systems more comparable to Canada than Australia and New Zealand. Furthermore, the three states share a common history of settler colonialism and grapple with similar legacies of institutionalized racism towards the respective indigenous peoples within their borders. Therefore, there is value in comparing the Canadian experience to those of Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.

This was an opinion shared by the Canadian House of Commons Special Committee on Electoral Reform (ERRE). Established in 2016, the ERRE was a multi-party committee formed to evaluate the viability of different alternatives to the first-past-the-post electoral system. Throughout 2016, the Committee held several formal hearings, and met with officials from Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, amongst other states, to learn from their experiences with electoral reform.

Australia has used a system of ranked ballots for its lower house elections since the early 20th century. Under the instant-runoff voting or alternative vote systems, Australian voters are able to rank their choices for Member of Parliament in constituency elections. This voting system ensures that if an Australian voter’s first choice does not meet a certain threshold of support, their votes will still nonetheless count towards their second or even third choice. This ensures that the winning Member of Parliament receives at least 50% of the vote.

In order for votes to count, however, Australians must rank all candidates on a ballot. This, coupled with the fact that voting is mandatory in Australia, has led to a rise in “donkey voting.” This is a form of protest vote, in which a voter ranks candidates on their ballot in numerical order as listed. It is with this in mind that the Canadian ERRE recommended against forcing voters to rank all candidates. Likewise, the ERRE advised against mandatory voting, as it would mask the root cause of voter apathy.

Ranked ballots, however, were personally preferred by the Prime Minister early in the debate over electoral reform. Ranked ballots furthermore are not entirely foreign to Canadians, having been used in the leadership races for Canada’s Liberal and New Democratic parties. However, a poll conducted for the Broadbent Institute has shown that of all proposed alternatives, the ranked ballot garners the least support from Canadians, with only 14% approval. Rather, the poll showed that a substantial plurality of Canadians, approximately 43%, prefer the status quo.

A similar result was found in the United Kingdom. In 2011, Britons went to the polls to vote on electoral reform. Voters were asked if the United Kingdom should adopt a ranked ballot for constituency elections, as seen in Australia. The campaign quickly became partisan, with smaller parties, such as the Liberal Democrats, supporting the change, hoping to gain from it. The Conservative party, on the other hand, sought to defend the status quo, fearing that a change to a ranked ballot would increase the number of smaller parties in parliament. This, in turn, would have hypothetically led to more minority governments in parliament, disrupting the ability of the Conservatives to rule alone.

The referendum, however, would fail, with 67.9% of Britons voting against the change. This was particularly shocking to those in the pro-reform camp, as polls conducted months before the referendum had demonstrated significantly greater support for a ranked ballot. However, the ‘no’ campaign was criticized by the opposition for spreading misinformation, allegedly fabricating the financial costs of switching to a new electoral system. Additionally, government pamphlets explaining the alternative vote system reportedly made the ranked ballot seem overly complicated, dissuading voters.

The combination of partisanship and misinformation in the British referendum has called into question the role of plebiscites in deterring major institutional change. As one British official for the Electoral Reform Society put it in her testimony to the Canadian ERRE, “done badly, a referendum can obliterate any chance of meaningful public and political debate, as the ballot topic is completely overtaken by proxy issues.” With this in mind, the ERRE recommended that the government nonetheless hold a referendum on electoral reform, with the caveat that Elections Canada provide as much non-partisan information on potential changes as possible.

However, The Broadbent Institute poll revealed that despite a plurality of Canadians supporting the status quo, and rejecting the alternative vote, 27% were in favour of a shift towards a Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system and 17% supported Pure Proportional representation. Thus, if tallied together, slightly more Canadians would rather have a more proportional system than the status quo, approximately 44%. Briefly, a Pure Proportional system would eliminate all constituencies, with the nation as a whole effectively becoming one large riding. Parties would thus be accorded seats in direct proportion to the percentage of votes received in a general election. MMP, on the other hand, maintains the existence of ridings. In MMP systems, citizens are granted two votes. With one vote, they elect their preferred candidate in their riding, whereas with their second they select their preferred party to lead the nation. Members of Parliament can still under MMP win a riding seat with a plurality of votes. However, the party vote corrects for this imbalance, guaranteeing seats won in constituency elections while affording parties additional seats based on their share of the national vote. The proportionally elected Members are selected from party lists. This in turn creates a parliament that more accurately reflects voter preferences.

MMP has been utilized in New Zealand since the 1996 election. Since then, MMP has been cause for several positive consequences in the country. For one, the practice of strategic voting has been largely eliminated in New Zealand, citizens being able to choose their preferred candidate without fear. In fact, approximately 30% of New Zealanders have taken up the practice of “cross-voting”, supporting different parties with each of their two votes. This allows local candidates to run for office on their own merits, instead of relying on partisanship. MMP has also led to significantly more women and indigenous people being elected to New Zealand’s parliament, their seats assured by proportionality and party lists.

New Zealand has also had since 1867 reserved seats in Parliament for its Maori indigenous people. Initially, these special constituencies were conceived as a means of social control by colonial officials, who sought to placate demands for self-governance and assimilate the Maori. Some have since called for the abolition of these special constituencies, particularly the leader of the New Zealand First Party, Winston Peters, himself of Maori descent. However, according to a report by the Canadian Library of Parliament, there is not significant support amongst New Zealand’s indigenous population to abolish these seats, with many Maori instead seeing them as “a vital component of their cultural heritage” despite the colonial legacy of these seats. A similar system could be imported to Canada, and would go a long way in fulfilling the government’s promise to reconcile with indigenous peoples. Furthermore, a recent survey by The Environics Institute has shown that 46% percent of Canadians support guaranteed indigenous representation in parliament, with another 29% responding it “depends” on how this change would be implemented. Therefore, it is likely that the general public would support some form of assured representation for indigenous people. However, a change of this magnitude could not be implemented without significant consent from Canada’s diverse indigenous population, given the history of reserved seats being used as a tool of colonialism. Thus, if ever implemented, the Canadian government must be careful to avoid top-down paternalism, as well as respect treaty rights and obligations.

It is no doubt that the end of the electoral reform process came as a great disappointment to many Canadians. However, with an upcoming election in 2019, and new ambitious leadership for both Canada’s NDP and Conservative parties, it is likely that the issue will surface once again. If electoral reform is put back on the table, it would be a great loss if Canada were to ignore the wealth of experience that can be drawn from the international community. Although no two states are ever completely comparable, Canada’s Commonwealth allies share government institutions closer than any other states. If equitable reform has been possible in New Zealand and Australia, there is no reason it cannot be made possible here. Likewise, there is as much to learn from the failures seen abroad as there is to learn from successes, the United Kingdom’s referendum coming to mind.

All things considered, Justin Trudeau’s promise to end first-past-the-post in Canada by the next election has opened the floodgates. It is unlikely that they will ever be closed again.

Christopher Ciafro is a second year McGill student, completing an Honours Degree in Political Science.

Edited by Luca Loggia