Congo’s Ebola Problem: More Than Just the Disease

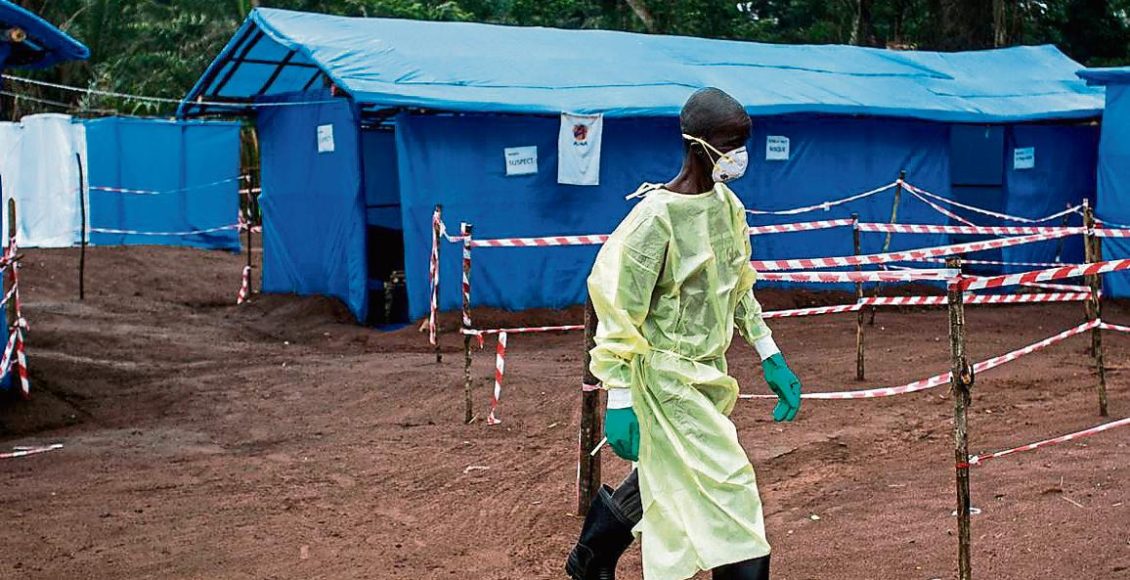

On August 1, 2018 the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) Ministry of Health declared an outbreak of the Ebola virus disease (EVD) in the country. Largely concentrated in the province of North Kivu, the fatal illness has claimed the lives of 531 people, with the number of total documented cases amounting to 853 as of 20 February 2019. The circumstances in the DRC are particularly troubling due to the country’s high population density, mass displacement, and ongoing violence.

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) has been a major actor in responding to the crisis. Due to the DRC’s mostly landlocked position in central Africa and the fact that North Kivu shares a border with Uganda and Rwanda, the concern for further spread of EVD has required bilateral collaboration between the DRC and neighbouring governments. As of December 22nd, 2018, 71 points of entry have been determined in northeastern DRC thanks to the work of the DRC Ministry of Health, International Organization for Migration (IOM), UNICEF, and WHO.

There are currently over 4.5 million displaced peoples within the DRC, 12.8 million people “in dire need of assistance,” and over 536,000 displaced refugees from surrounding countries, with the top three countries of origin being Rwanda, The Central Africa Republic, and South Sudan. Due to the complex political climate, the there is the potential for the crisis to escalate and result in even more widespread infection in the region. The complex circumstances make it nearly impossible to track and register undocumented people who may have carried the virus into the region or who may have left the region infected, further complicating the ability to trace where patients have been and who they have been in contact with.

This outbreak of EVD differs from the West African outbreak in 2014 due to high population density in the vicinity of possible infection. On November 5th 2018, Tom Inglesby, Director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security stated that “If Ebola becomes endemic in substantial areas of North Kivu province, in northeastern Congo (…) there would be a sustained and unpredictable spread of the deadly virus, with major implications for travel and trade.” For comparison, there are approximately 6 million people in the province of North Kivu alone, while the entire population of Liberia, the country where the West Africa Ebola epidemic of 2014-2016 was most deadly, is only about 4.8 million. In a region ravaged by conflict and a rapidly unravelling refugee crisis, an EVD endemic of this scale would be catastrophic.

While the DRC has suffered from internal conflict for centuries, since the country’s independence from Belgium in 1960, recently, a number of new actors and belligerents have joined the conflict causing a general upsurge in violence across the region. The length and brutality of extractive colonial practices continue to influence ongoing conflict, particularly the country’s control over their vast supply of natural resources, primarily cobalt, copper, and diamonds. The current conflict is taking place between the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), Mai Mai Sheka, Mai Mai Yakutumba, and the non-aligned Islamist group Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) and the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC), The United Nations Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo (MONUSCO), and pro-government Mai-Mai militias.

SSgt. Jocelyn A. Guthrie, U.S. Air Force

The toll of the warfare will only exacerbate the EVD epidemic, with an increasing number of health problems, gender-based violence, mass destruction of property, displacement, and death putting continued stress on the governments and NGOs involved. As well, with a recent presidential election plagued with illegitimacy and serious accusations of corrupt practices resulting in the victory of opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi, the future of the DRC’s role in providing accountable and appropriate forces to combat both the violence and epidemic are not completely clear. To make matters even more volatile, voting in the North Kivu districts of Beni (8 seats), Beni village (2 seats), and Butembo village (4 seats) for the federal election was postponed until March 2019, with the federal election chief citing a need to control insecurity and the EVD outbreak. These regions are in urgent need of government assistance, aid, and coordination, and this delay hinders their ability to have their concerns expressed and ultimately met.

North Kivu remains the epicentre of the outbreak, and while the region has received significant aid and attention, poor practice and structural problems have prevented any kind of permanent progress. In the communities of Butembo and Katwa, 86 percent of Ebola cases since Dec. 1 “had visited or worked in a health care facility before or after their onset of illness,” according to the World Health Organization. While Relais Communautaire, a “network of community volunteers who act as interface between communities and the healthcare system” have visited over 185,00 homes in the cities of Beni, Butembo, Katwa, Mabalako, Tchomia, and Oicha in North Kivu, due to the political turmoil it remains difficult to collect accurate information on EVD, particularly in terms of who has come into contact with the disease.

In Butembo and Katwa, a “majority of new cases are not known contacts, or are known contacts who were not followed, due in part to community resistance” and “health care workers currently represent 16% of all cases.” These worrisome statistics demonstrate a lack of engagement with the communities at risk, possible poor practice, and late onset treatment of already infected people. While the EVD vaccine has supposedly been given to 90% of “eligible and consented persons,” the disturbingly high number of health workers infected signifies that these numbers may have been distorted.

The Ebola outbreak in the DRC shows no signs of slowing down, yet increasing access to vaccines for at-risk groups, continued strategic monitoring of EVD cases, and engaging civil society leaders in communication with local communities is a step in the right direction. With 46 radio stations in Beni, Mabalako, Butembo, Tchomia and Katwa, which “include programming to dispel EVD rumours, increase awareness of the signs and symptoms of EVD, safe and dignified burials, and broadcast testimonies from survivors on the experience of patients in ETC,” more effective infrastructure is being built in consultation and collaboration with the hardest-hit communities. While there is potential for improvement, this crisis will continue to demand huge investment and coordination among the various parties involved. Due to the possible powder-keg of internal structural issues, the outbreak has the ability to create a prolonged period of endemic EVD and heightened hostility between civilian combatants, government forces, and a general public in distress.

Edited by Allegra Mendelson.