Corporate Social Responsibility: Capitalist Corruption or Genuine Aid?

According to the UK Business Consortium, 78% of consumers said they were more likely to purchase from a company that supports and engages in activities to improve society. This incentivizing fact has prompted the proliferation of a practice known as corporate social responsibility or CSR, where companies “integrate social and environmental concerns in their business operations and in their interaction with their stakeholders on a voluntary basis” in the hope of promoting profit at a nexus with societal benefit.

CSR programs have often aimed to alleviate societal inequalities, such as Gap’s P.A.C.E. Program which focuses on institutionalized gender disparity, or People Water’s ‘Drop for Drop Campaign’ which promotes rural development. However, it seems that while conceived as altruistic and focused on eroding systemic inequality, the role of corporate social responsibility does more to propagate the very preexisting systemic inequality it purportedly fights against. But how is this so?

To begin, we note CSR’s effect on low-income populations. CSR as a whole is destructive as it liquidates developing low-income industries that disproportionately affect poor communities. One of the most pressing issues is that goods that CSR-sponsored charities often donate to are not goods that low-income communities need, and because they are donated freely, these goods erode the pre-existing industries in the country of donation. The most famous example of this is the TOMS shoe “One for One” model, in which TOMS donates a pair of shoes to an underdeveloped country for every pair bought by Western consumers. The problem with this model is that it floods preexisting shoe markets with free shoes which consumers will, of course, accept instead of buy shoes. The issue with this is evident to author Jacqueline Barter who states:

“TOMS Shoes out-competes the local shoe industry and therefore decreases or inhibits local infrastructure and economic development. TOMS seems to create the idea among its customers that there are no existing shoes available in the markets they serve. This argument is largely unfounded as most of the markets they serve have some existing shoe sales. On TOMS own blog, we see lines of children waiting to receive their shoes – each already wearing a different brand of shoes on their feet”.

And as these preexisting shoe industries are often dominated by local artisans and cobblers who make up the low-income populations of these nations, by destroying their industries, CSR program’s like TOMS keep low-income artisans in a perpetually impoverished state. And for the low-income consumers of these shoes, TOMS is harmful. As corporate charities do not donate regularly, the sporadic nature of donations means there are long periods where low-income populations are without an option for shoes as their local industries are destroyed, and there is no promise in TOMS donating to their region again, as TOMS efforts span over 73 nations, making it unfeasible that the same community would receive constant care.

Additionally, another complication with corporate social responsibility is that it exacerbates a Western divide between Christianity and other global religions. CSR programs are often undertaken by Western institutions who hold more market share and wealth, most significantly in North America and Europe, both areas that have incredibly high concentrations of Christians. Even historically, Christian faith has had a stronghold in Europe, where it developed institutional power, and it has only truly been proliferated through the globe by colonizing missionary forces. The problem with CSR programs is that they traditionally ally with Christian charities, such as Compassion International or the Salvation Army, due to the strength of Christianity in the West. However, this is an issue due to the fact that when delegating aid, there is a noticeable trend that these organizations favor Christians over other, less Western, religious groups.

For instance, the company Tyson’s Food, the second largest producer of meat-based products in the world, has publically donated millions to the charity known as Bridge2Rwanda, which aims to promote investment in Rwandan schools and provide global education opportunities for Rwandan scholars. On the surface, this appears to be a positive contribution to Rwandan society, and admittedly, for many it is. However, the organization becomes much more nefarious when you look at through the lens of religion. Bridge2Rwanda is a Christian charity, partnering with prominent religious figures such as Rwandan official and Anglican bishop John Rucyahana. Rwandans who interact with this organization are often those most entrenched in Christian institutions like the Rwandan Church, and individuals who are most visibly not Christian are often overlooked and ignored in turn for more outwardly Christian individuals. And as Rwanda is overwhelmingly Christian, with 94% of Rwandans identifying with Christianity, this places those in the minority, (most prominently the 1.8% of Islamic Rwandans and the 1.2% of Rwandans who follow folk religions) at a further systemic disadvantage to accessing the educational resources that Christian Rwandans are guaranteed.

The issue of charities having excludable benefits for those who best correspond to their religion is not the only religious issue prevalent with CSR practices. Another issue is that workers who are attracted to companies which have abundant CSR programs and safe-working practices are molded into the companies more Western moral view, which often rallies against minority faiths and practices. As stated by Geerte de Neve, “along with the regulation and standardization of production processes, ethical codes and standards also spread values and create persons and selves. They form an explicitly classificatory device that ranks people according to the extent to which they have internalized the values that standards embody”. Essentially, for those in developing nations to gain employment under CSR initiatives, they must internalize the Western morals espoused by said companies. And as morals are invariably tied to religion, it’s clear that by adopting more Western, Christian morals, companies are setting a systemic precedent that undermines minority religions.

For instance, the question of child labour is one of these moral conflicts. While Western values disparage the practice of child labour, in many nations, ranging from the Bantu regions of Africa, to the Philippines, it is not viewed as problematic, but rather children are, according to the International Program on the Elimination of Child Labour, “impelled to work from an early age because of the centuries-old tradition that the child must work through solidarity with the family group, so as to compensate as much as possible for the economic burden that he/she represents and to share in the maintenance”. This condemnation of a tradition, which some do see as a positive, could also be seen as an erosion of a minority’s culture, which is equally problematic.

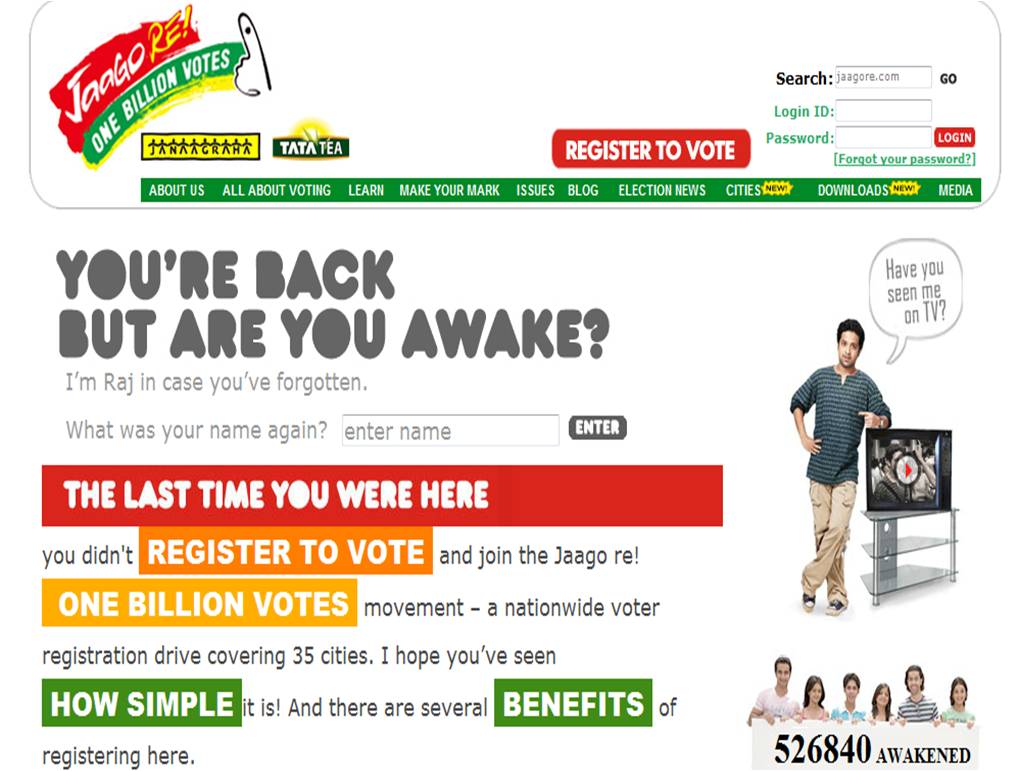

All in all, CSR, as it is conceived today, is a practice that appears positive, allowing its negative externalities to be overlooked. However, CSR as an ameliorative strategy is not completely useless, as there are occurrences in which successful CSR practice has advanced a more equitable society. For instance, the corporation Tata Tea, who bases their CSR in India, has implemented programs such as their “Jaago Re advocacy platform”. The Jaago Re program has been aimed at disseminating information regarding specific Indian elections, most often when votes retain to gendered issues. For instance, their ‘One Billion Votes’ initiative aimed at promoting voting in low-turnout regions of India. Data has statistically shown that the program leads to increased engagement across genders, increased communication, and decreased acceptance and perpetration of violence.

The success of this program, unlike other CSR programs, is on the attention to details, as Tata Tea has made it a mission to individualize their programs to specific countries and populations, detailing specific Indian actors and regional forces at hand. Where programs like TOMS failed to individualize their shoe donations to countries that actually lacked shoe industries, or where Tyson’s Food failed to individualize their sponsorship to minority religions, it is apparent that CSR needs to be about the specificities and nuances of the country it is applied to, and not a blanket “holier-than-thou” aid strategy that prioritizes corporate interests over actual amelioration. To put it simply, what is the point of corporate social responsibility if the program prioritizes the corporate over the responsibility?

Edited by Andrew Figueiredo