Corruption in Vietnamese Education: Major Issues

Attempting to enhance its education system, Vietnam had set several goals for 2006 and 2010 through at the Higher Education Reform Agenda. The event set several aims for the country’s tertiary system, such as increasing the participation rate at universities; enhancing the quantity, quality, and efficiency of the education system; as well as skills training; increasing the number of graduates entering the labour market, and improving governance of the higher education system. Vietnam is also aiming to have at least two institutions appear in worldwide rankings by 2020 (Dennis, 2012). Given the country’s pervasive corruption, however, it is questioned whether Vietnam could reach its great expectations.

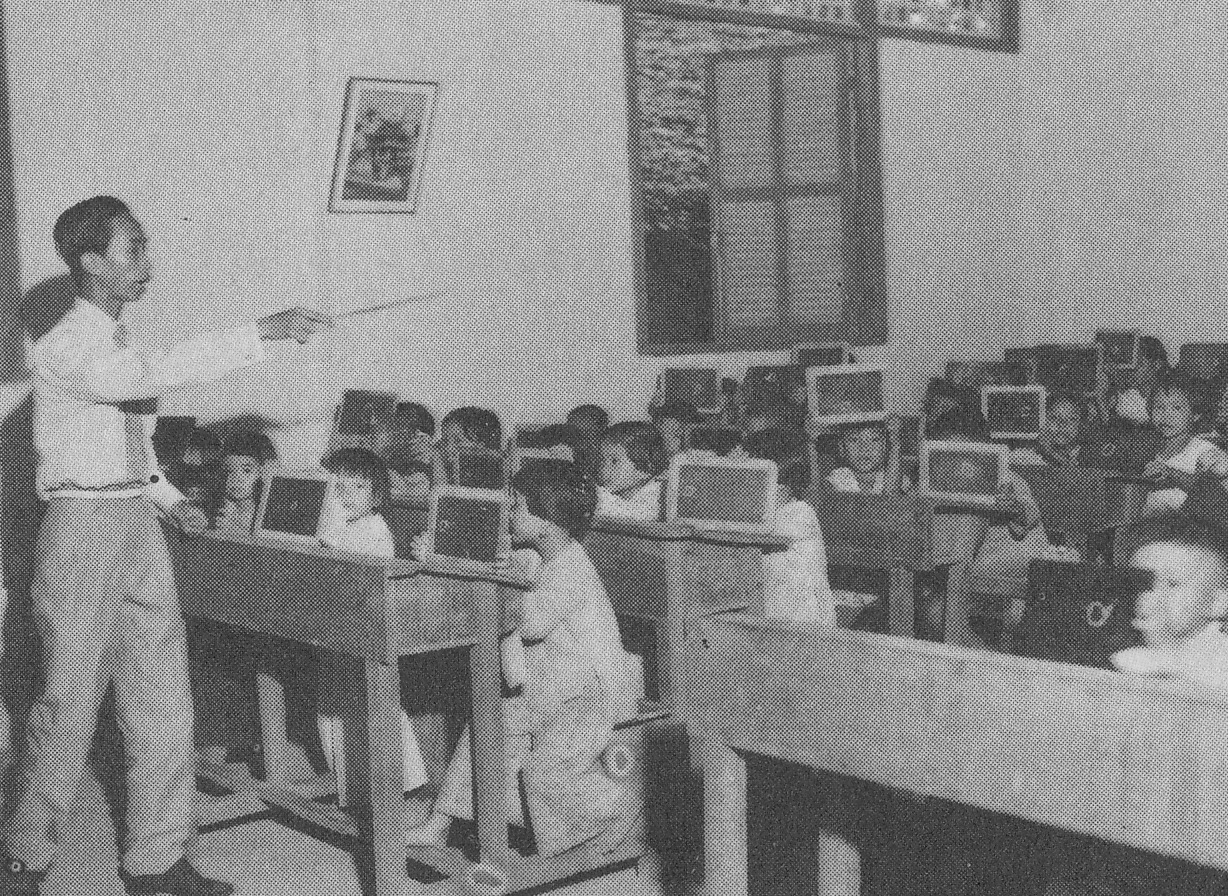

Vietnam has traditionally been committed to education, dating back to its Confucian roots. In 1989, Vietnam adopted a “market-oriented socialist economy under the state guidance”- known as Đổi Mới. Since then, the country’s education system has undergone significant changes, moving away from the Soviet model to the demands of a market-oriented economy (Dennis, 2012). The country also set several goals for its education system. To reach such great expectations, however, the country should solve the challenges that can hinder the development of its education system, especially corruption. In this article, I will explore how the role and the attitudes of parents, students, and teachers create difficulties in anti-corruption and then look at the consequences of the current problem on the country’s tertiary education system.

Generally, corruption isn’t uncommon in Vietnam (Davies, 2015) and is relatively apparent in the education system. Compared to other countries, bribes to access public schools in Vietnam are relatively high. Specifically, about 46 to 60% of individuals paid bribes in order to access public school, which is the second highest bribe after other services (Transparency, 2017)

The road to fight corruption in schools is not easy because of the attitudes of students and parents, which are relatively relaxed (Dennis, 2012) towards the problem. For questions referring to corruptive behaviours, it is shown that an average of 88% of youth considered many behaviours to be wrong, close to 91% of adult respondents. On the other hand, these values are specific to situations. Considering Figure 4 below, there are scenarios where students support and engage in corrupt practices. Especially when faced with the situation such as “exploiting relationships to get into a school or company”, youth considered this to be acceptable. The youth also take decisions to participate in corruptive behaviours that violate their integrity, creating chances for this practice existed. Importantly, parents also share the same views on corrupt practices as students, which is engaging in and supporting corruptive practices in the education system. In Dennis’s study (2012), the researchers set several scenarios and asked parents which corruptive behaviours they believe to be reasonable. And strikingly, they found that parents believe this view to be reasonable regardless of scenarios raised by the questioners (Dennis, 2012).

Parents also create chances for corruption to exist, making fighting corruption in educational environments harder. In an article on Viet Nam News titled “Parents blamed for role in teacher corruption” (2010), parents’ view towards corruption is shown to be partly due to their desire to have their children attend good public schools, rather than private schools. The writer also showed that parents would abet teachers and educators in their corruption so long as they think it is good for their children. In addition, parents are willing to pay extra for teachers to include their children in extra-curricular teaching for low- and high-achieving students, “otherwise they feel their children are being left out” (Vietnam News, 2010). This shows that the nature of corruption in education partly originates from the willingness of parents to pay for better education for their children.

Besides parents and students, teachers are also individuals that make anti-corruption processes more difficult. As a matter of fact, teachers possess power through their professions. Teachers are “gatekeepers” of education, knowledge, and qualifications; their power, along with opportunities and benefits they control, created opportunities for corruption to exist (Tanaka, 2001). Many teachers, for instance, hold extra tuitions, outside of regular school hour, for a small fee of between $2.50 and $5 per lesson (Davis, 2016). The motivation here is to have income supplemented for their low wages.

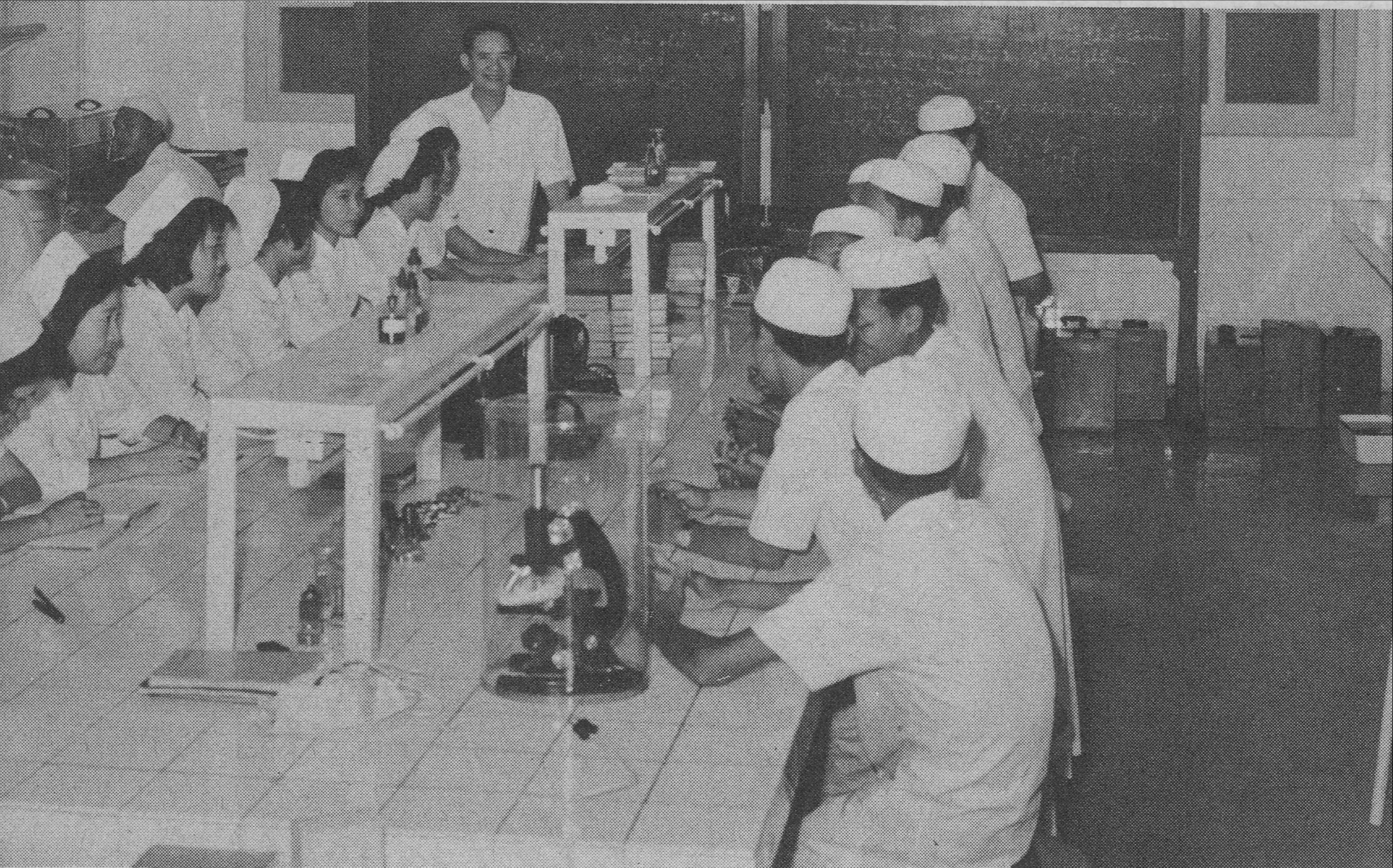

The existence of corruption in educational environments has left large impacts on teaching quality at tertiary levels. The problem not only hinders the quality and quantity of education but also negatively impacts society as businesses and employers find that many college and university graduates are ill-prepared to compete in the real world (Harman et al, 2010).

The combined number of peer-reviewed journals of two Vietnamese universities was 96 publications, which is the lowest in the region. Thomson Reuters, the company where the information for the table was collected, selected high-impacted journals in each category. This showed that the teaching standard and the curriculum in Vietnam remained relatively low when compared to other countries in the region. Moreover, Vietnamese universities are producing incompetent workforces to meet the demand of the economy as well as society. As recounted in a paper analyzing the crisis in Vietnam’s higher education system, Intel struggled to find engineers for its manufacturing facility in Ho Chi Minh City. And the company finally confirmed that Vietnam’s graduates achieved the worst result they have encountered in any country they invest in. These examples illustrate how pervasive corruption in Vietnam’s educational system hinders its quality and consequently prevents institutions from producing rigorously trained graduates for employability.

In conclusion, corruption has negative impacts on Vietnam’s education system. Compared to other countries, Vietnam has a high level of bribes paid to access public schools. These practices exist due to the relaxed attitudes of both parents and the youth towards this problem. Moreover, the low wages and powerful role of teachers partly contributed to the current problem. As a result, corruption in the education system has lowered the teaching standards at schools, especially at higher education levels, resulting in a low-quality training and not producing enough well-equipped graduates in order to meet the demand of society and the economy. In order for Vietnam to reach its great expectations for the 2020 period, Vietnam should consider fully solving its pervasive corruptive behaviours. When Vietnam’s educational environment is covered with integrity, it can provide students with equal chances to attend schools, enhance the country’s teaching quality and help Vietnamese schools appear alongside other top universities on worldwide rankings.

Edited by Frankie Wallace

References:

- Davies, Nick. 2015. ‘Vietnam 40 Years On: How A Communist Victory Gave Way To Capitalist Corruption’. The Guardian. Available at: http://www.theguardian.com/news/2015/apr/22/vietnam-40-years-on-how-communist-victory-gave-way-to-capitalist-corruption. Accessed November 11, 2017

- Davis, Brett. 2016. ‘Public Sector Graft An Issue in Vietnam, But There Could Be One Simple Solution’. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/davisbrett/2016/08/22/public-sector-graft-remains-an-issue-in-vietnam-but-there-could-be-one-simple-solution/. Accessed November 11, 2017

- Dennis C. McCornac, (2012),”The challenge of corruption in higher education: the case of Vietnam”, Asian Education and Development Studies, Vol. 1 Iss: 3 pp. 262 – 275

- Harman, G., Hayden, M and Nghi, P.T. (Eds) (2010), Reforming Higher Education in Vietnam. Challenges and Priorities, Springer, Dordrecht.

- Transparency International. (2017). People and Corruption: Asia Pacific. Transparency International, pp.18-19.

- Tanaka, S. (2001), “Corruption in education sector development: a suggestion for anticipatory strategy”, The International Journal of Educational Management, Vol. 15 No. 4, pp. 158-66.

- Valleley, T. and Wilkinson, B. (2008). VIETNAMESE HIGHER EDUCATION: CRISIS AND RESPONSE. [PDF] Cambridge, MA: Harvard Kennedy School: Ash Institute for Democratic Governance and Innovation, p.2. Available at: https://sites.hks.harvard.edu/innovations/asia/Documents/HigherEducationOverview112008.pdf (accessed 14 Nov. 2017)

- Viet Nam News. (2010). Parents blamed for role in teacher corruption. Vietnam News. Available at: http://vietnamnews.vn/society/205800/parents-blamed-for-role-in-teacher-corruption.html#D42puQBP3K7Bu2xq.97 (accessed on November 11, 2017)