Costa Rica’s Caribbean Coast: Unpacking Afro-Costa Rican Identities

"Puerto Limon" by Gail Frederick is licensed under CC BY 2.0

"Puerto Limon" by Gail Frederick is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The lush and versatile landscape of Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast reflects the history and roots of the area’s Afro-Costa Rican community. But unlike the rainforests and beaches, it is rarely explored.

At some point, Afro-Caribbeans in the Limon province never crossed further than Turrialba, situated between the port city and the central valley. They founded towns alongside the Caribbean coast in the Limon province, a rural area thriving off agriculture, fishery, and its port. According to Limonese locals I’ve conversed with during my time here, ethnic and linguistic differences were barriers that kept the Afro community away from mestizos. Those lines translated physically through spatial segregation. However, with time, resource limitations have triggered rural to urban migrations from the Limon province towards the San Jose metropolitan area. General ignorance of the complexity of Afro-Costa Rican history and identity affects how they move through the country and understand themselves. During my time in Talamanca, I got the opportunity to speak with various local Afro-Costa Ricans and their community leaders about their history and experiences. One is Dr. Natasha Gordon-Chipembere, an Afro-Costa Rican and Panamanian writer, professor, and expert on the historical trajectory of blackness in Costa Rica. During a Zoom interview, she shed light on the history of Afro-Costa Ricans and the Limon province and her personal experiences navigating the country as an Afro-Costa Rican.

“What we’re looking at is the historical trajectory of blackness in Costa Rica. A lot of people think it’s those who end up in Limon. […]. I understand the presence of blackness in three different ways. The first wave is the presence of Afro-Iberians who came with Christopher Columbus and the expedition.”- Dr. Natasha Gordon-Chipembere

In the sixteenth century, Afro-Iberians of Spanish-Moore descent arrived with Christopher Columbus’ expedition. Although he docked in Cahuita, early colonizers settled in the central valley on the Caribbean coast, founding Cartago as the capital due to its temperance. Dr. Gordon-Chipembere explains: “In contrast to other terrains in Central America or the southern United States, Cartago did not have land suitable for cash crops. […] Although there was cacao and coffee, production was not enough to be competitive in the global market.” Within the context of the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, enslaved people were not brought directly to Costa Rica. Instead, many of them were smuggled from other regions in the Americas, specifically neighbouring Panama, where a major slave market existed in the city of Portobelo. Enslaved people were forced to work in the cattle ranches of Matína in the Guanacaste region and the cacao plantations in the Nicoya province. Spaniards, however, were not wealthy and could not afford to maintain authority over slaves.

As Dr. Gordon-Chipembere recounts, owners of the plantations were also absent most of the time, leaving enslaved people to work the fields autonomously. Men had children intentionally with Indigenous women, as they were free from enslavement. Thus, any offspring born from these couples would also be free. Enslaved women were primarily found in Cartago, working as housekeepers and concubines. Puebla de Los Pardos was also founded, a township for free people of African descent. Today locals in those areas are descendants of these mixed ethnic couples.

Slavery was officially abolished in 1832, a few years following the country’s independence from Spain. By this time, Costa Rica had started exporting cacao and coffee to the European market. To increase efficiency, the government looked to build a railroad from San Jose to Puerto Limon. The Limon province already had a few established communities in Cahuita, Puerto Viejo and Manzanillo. In 1750, Afro-Caribbean fishermen from nearby Panama had started making annual rounds to the area for turtle hunting, eventually founding the coastal towns.

As Dr. Gordon-Chipembere elaborates, “Up until this point, the Pacific coast had been serving as the main port. Ships coming and leaving had to pass from San Jose, go under South America and come back up to get to the Atlantic.”

After failed attempts from the government to construct the railroad, employing Chinese, Italian, and African-American labourers, they opened a contract with American entrepreneurs Minor Keith and Henri Meiggs in 1871. Keith employed a mainly Afro-Caribbean workforce from English-speaking Barbados and Jamaica. Their close linguistic ties made communications easier for the railroad construction. On December 20, 1872, the ship Lizzie docked in Puerto Limon from Kingston, Jamaica, transporting the first 123 workers. This established a direct link between the coast and the island. These newcomers found their place among Afro-Caribbeans already established in the coastal towns, which stretched from Puerto Limon to Manzanillo. Afro-Costa Ricans thrived along Limon’s coast, either through cacao farm plantations or working for the railroad industry.

“Limon becomes an enclave for Afro-Caribbean English-speaking Baptist or Methodist community. These are not enslaved people, they are educated already and have very specific skills.” – Dr. Gordon-Chipembere

Despite residing in Costa Rica, these migrant workers from the Caribbean kept allegiance to Jamaica, identifying ethnically with such. They did not look in towards Costa Rica’s central valley and instead focused their attention outwards to the Atlantic and the cosmopolitan nature of Puerto Limon. Afro-Costa Rican identity is thus split in two ways, as Dr. Gordon-Chipembere broke down. Those in Guanacaste and Cartago, regions close to the Pacific coast descended from enslaved Africans and mestizos, consider themselves to be only Costa Rican, or “tico.” However, Afro-Costa Ricans in Limon, whose great grandparents arrived willingly for economic opportunities, identify as Afro-Caribbeans for the most part and favour English or Limonese Creole as their mother tongues. As many have expressed to me, speaking these languages is one of the ways they hold onto their Caribbean identity and resist cultural erasure within their Hispanic environment.

Part of the reason Afro-Caribbeans had limited contact with Hispanic Costa Ricans was due to laws that prohibited them from migrating past Turrialba. Despite two generations of Afro-Caribbeans having been born and established in Limon by the 1930s, they had not been granted Costa Rican citizenship and were considered stateless. Only in 1949, following the Costa Rican civil war, were they offered citizenship. “My grandmother had to apply for citizenry even though she was born here,” shares Dr. Gordon-Chipembere.

The naturalization process unravelled on the condition that the children of Afro-Costa Ricans study at Spanish-speaking schools. This did not sit well with the Afro-Caribbeans, who had their own Jamaican educational establishments and teachers. A few Afro-Costa Ricans I’ve encountered shared how some hid their children from authorities to keep them from having to attend these schools.

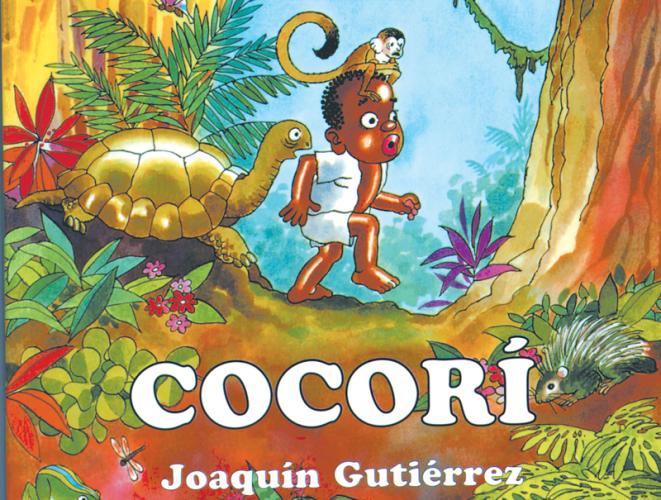

Spatial segregation of Afro-Caribbeans in Limon persists, and Costa-Ricans from the central valley channel eurocentric ideals in their projections of Limon. Hispanics “other” and exoticize Limoneses. During the interview, Dr. Gordon-Chipembere explained the controversial Cocori caricatural children’s book.

Written in 1947 by Joaquin Guitierrez, Cocorí tells the story of a young Limonese boy called Cocori, who lives in the jungle, speaks with animals, and walks around barefoot. His depiction has a stark resemblance to typical blackface theatrical makeup. He eventually encounters a young blonde girl dressed in western clothing, portrayed as the protagonist’s saviour. Despite the book’s questionable ethics, the government required all public schools in Costa Rica to add it to its curriculum. After persistent debates and interference from the United Nations, the government removed it from the list of required reading. However, it can still be taught at professors’ discretion. Dr. Gordon-Chipembere recounts how her son was taunted with the term “cocori” at his arrival at his high school in San Jose. As he was born and raised in the US up until that point, he did not understand what it meant at first. Yet, once they found out the origin of the word, he quickly shut down the taunts. In her words, “it was like being called the n-word.”

Despite the performative whiteness mestizos instigate in their relations with Afro-Caribbeans, an increasing number renounces their origins in favour of Hispanic identity and language. This is motivated by the opportunities available in the central valley absent in the Limon province and a wish to be fully immersed in Costa Rica as Ticos. This trend contrasts heavily with Marcus Garvey’s iconic legacy in Puerto Limon. A black nationalist of the early twentieth century and founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), Garvey founded the Association’s 300th branch in Puerto Limon, one of the few still active globally. The organization’s mission and values have played a key role in ongoing developments within the community, as Afro-Costa Ricans continue to support themselves and protect their culture despite the structural barriers they face.

Featured image: “Puerto Limon” by Gail Frederick is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Edited by Grace Parish