A Crisis in Two Parts: Mongolia’s Buddhism Question and its Economic Failings

The 14th Dalai Lama speaks to a crowd of thousands at Gandantegchinlen monastery. http://www.dnaindia.com/world/report-dalai-lama-preaches-in-mongolia-risking-china-s-fury-2275112

The 14th Dalai Lama speaks to a crowd of thousands at Gandantegchinlen monastery. http://www.dnaindia.com/world/report-dalai-lama-preaches-in-mongolia-risking-china-s-fury-2275112

On Friday, November 18, 2016 the 14th Dalai Lama arrived in Ulan Bator to begin a four-day pastoral visit in Mongolia, a Buddhist-majority country. During his visit, he spoke to followers at the Gandantegchinlen monastery on the topic of materialism. According to the Mongolian government, his visit and teachings contained no overtly political content, and was largely spiritual in nature. On the same day that the Dalai Lama arrived, the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs put out a statement urging Mongolia to refuse the Lama’s entrance in the interest of their “sound and steady” bilateral tie development. Similar to past instances, the Mongolian government ignored the Chinese protests and allowed the lama a visa.

http://bit.ly/2iqtYOe

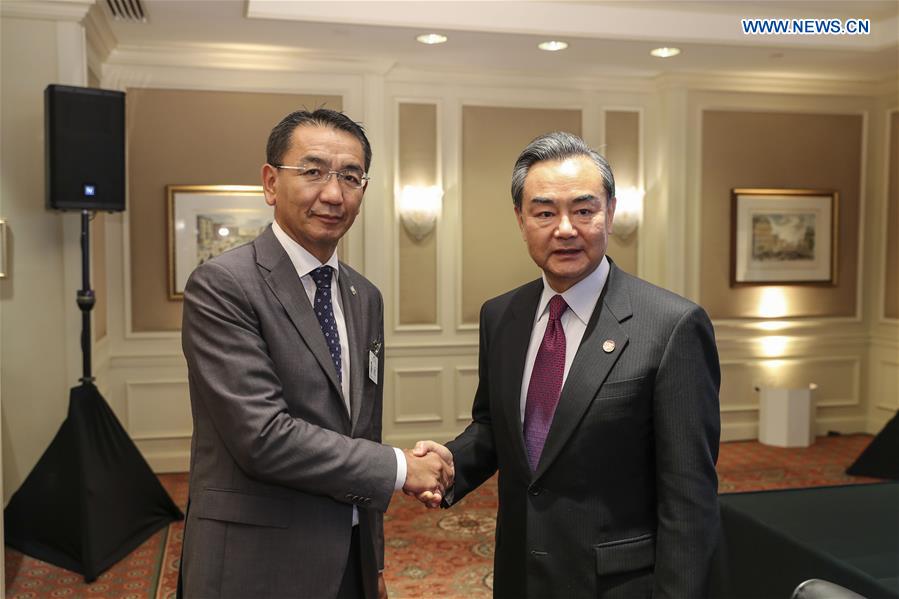

The reaction from the Chinese government was more forceful than in the past years. During the 2002 visit, China briefly closed its borders to Mongolia and during the 2006 visit Beijing cancelled its flights to Ulambataar. This time, the stakes have changed and leverage firmly favors China. Beijing promptly cancelled the planned bi-annual, bilateral meeting between Mongolian and Chinese foreign ministers. They also cancelled a meeting which had the intended goal of resolving Mongolia’s balance-of-payment dilemma through a 4.2 billion dollar loan. Additionally, they placed a tariff on goods exported from Mongolia to China at a border crossing with the most traffic. The border crossing in question, the Gashuun Sukhait pass, is the largest commercial point between China and Mongolia for Mongolia’s export market of copper and coal—including coal coming from a large mine which the Chinese state-owned Shenhua Group has its eyes on for development. The new transit fee is 10 yuan per truck and an additional 8 yuan per tonne. Independent mining analyst Dale Choi estimates that 900 trucks and 133,000 tons pass through daily. The Chinese foreign minister Geng Shuang has denied any knowledge of whether the new tariffs and diplomatic blocks are in response to the Dalai Lama’s visit. He stated that he was not aware of the tariff situation.

On December 21, the Mongolian Foreign Minister Munkh-Orgil Tsend told the Onoodor newspaper, “The government feels sorry for this.’’ He went on to say that the Dalai Lama “probably won’t be visiting Mongolia again during this administration.’’

Many have taken the statement to be an indication of an irrevocable censure on the Dalai Lama. Bloomberg politics entitled their report, Mongolia Vows No More Dalai Lama Visits After China Turns Screws. At a news briefing on the same day China’s foreign affairs spokesman Hua Chunying stated, “We hope that Mongolia will truly learn lessons from this incident, truly respect the core interests of China, honour its promise and make efforts to improve the relations between China and Mongolia.”

However, while the newly-elected parliamentary body will not change until 2020, the promise does not dramatically change the status quo considering that the Dalai Lama tends to visit Mongolia only once every four or five years-the last visit was in 2011, and before that 2006 and 2002. Despite the ambiguity of its duration and its fait accompli nature, the apology and censure is a dramatic change for Mongolia. Mongolia is 53% Buddhist, and it was the Mongolian Altan Khan who bestowed the title Dalai upon the visiting lama in 1577; Dalai is, in fact, a word from the Mongolian language meaning ocean.

The Economic Crisis

Mongolia is no longer as powerful as it once was; the age of the khans has disappeared into history, and even the success of 2012 is illusory. For Mongolia, the status-quo of this controversial conflict between religion and economy may be unsustainable in the face of pressure from Beijing, because its economy is in serious trouble and is dependent on China. In 2009, Mongolia resorted to the IMF for funds. The IMF agreed and supplied 242 million USD as a bailout. They toasted the deal with champagne, and indeed, the following several years seemed to prove their celebration to be well-founded; the government deficit and inflation rates went down, foreign debt arrears were paid, and there was a restoration of confidence in the Mongolian market which saw a 17.3% economic growth in 2012.

The good economic times did not last. By 2014, growth was down to 8% and then 2.3% in 2015. The Mongolian government invested massively in mining and other projects in the last couple of years. However, in the face of a world-wide decline in demand for copper (largely caused by China), Mongolia has yet to see a return on their expenditures which more than doubled their national debt this year to one billion. Attempts to help the matter by raising interest rates have done nothing but harm to the Mongolian economy. In August this year, Standard & Poor’s Global downgraded Mongolia’s long-term rating from B to B-.

Also important is that Mongolia’s economic complexity ranking has undergone a gradual but drastic decrease. This reduces their ability to handle a downturn in a specific global market and limits the breadth of interested international trading partners. 43% of Mongolia’s economy is copper, 29% is coal, and 27% is gold. China accounts for 80% to 90% of Mongolia’s export economy over the past six years.

Mongolia is in economic pain. To make matters worse, their dependence on China is not reciprocated by the latter to the same degree. The economic slowdown in Mongolia has roots in the declining commodities market in China. Another factor is that Chinese domestic copper production and processing have increased in the last several years. Any pressure that China might exert on Mongolia and any broken ties or stalled trade routes might marginally hurt China’s economy but it would destroy the financial sector in Mongolia. In this light, Mongolia’s question of whether to choose to heal the crisis of faith or the economic crisis is easy to answer.

The Crisis of Faith

China has long been in dispute with the Dalai Lama, whom the Chinese government views as a separatist and an enemy to the PRC. Following a failed uprising in 1959, the Dalai lama fled Tibet and found refuge in India. The PRC government has not allowed the Dalai Lama to return to the country since that time.

This is not the first time that the Chinese government has used political and economic pressure to sway third parties in the ongoing debate. The host country for the 2014 Nobel summit moved from South Africa to Rome, after South Africa refused the Dalai Lama an entrance visa.

A secondary factor beyond the economic and political imbroglio is that while in Mongolia the Dalai Lama announced that he was convinced that the Jebtsundampa Khatagt (Reverend Noble Incarnate Lama) had been reborn. This is the traditional name attached to the patriarchs of Buddhism in Mongolia which traditionally follow the same Yellow Hat Buddhist practice as the Dalai Lama. In Mongolia this patriarch is seen as the third most senior lama following the Dalai and then Panchem Lama. The rebirth of the Jebtsundampa Khatagt would ensnare China, Mongolia, and India in a theocratic and political difficulty. Following an imperial decree in 1758 all patriarchs of this line had to be born in Tibet, overseen by the Chinese Qing court and finally approved by them before the Dalai and Panchem Lama could approve them.

bit.ly/2ivmoOS

Mongolian citizenship would combat both Chinese interference and Mongolia’s internal, nationalist campaigns. The Dalai Lama has refused to publicly name the new Jebtsundampa Khatagt, as the young lama needs more years of training.

Factional politics within Mongolia, in which Buddhism and politics mix, could pit those with interests in Chinese trade against the new patriarch. A divide exists within the school separating the followers of the Shugden practice from rest of the Gelug school–this is the same school that the Dalai Lama follows. The Shugden followers revere Dorje Shugden, a mischievous and wrathful god who, its practitioners claim punishes the heterodox. The debate has evolved from its 17th century origins and is now largely a divide over the direction of Yellow Hat Buddhism– the Dalai lama believes in a school which is open to incorporation of other schools of thought while the Shugden minority advocate purging the heterodox aspects of the school. For years they have denied having connections to the Chinese Communist Party, but in December 2015 a Reuters investigation reported that there is a link; leaked CCP documents refer to the Shugden followers as “an important front in our struggle with the Dalai clique”. The same Reuter’s report quoted a former Shugden monk in India, Lama Tseta, who stated that he had received funding from the Chinese government to plan the activities of the sect abroad.

Some also speculate that as the Dalai Lama is quite old now, this process of announcing the rebirth of the Jebtsundampa Khatagt might prove to be a rehearsal of sorts for the future rebirth of the Dalai Lama himself.

In this encounter, Mongolia lost relatively little. Economically, trade became more difficult, talks and loans were stalled, and Mongolia lost face. They might possibly face less favourable deals from China when they finally sit down to discuss loans and trade with China and the IMF. However, the Dalai Lama had already completed his visit without incident and without interference. And the guarantee of no return extends only until the end of this terminal administration. However, considering the flight of investors from Mongolia in the last couple of years, Mongolia’s abysmal growth rates, its ballooning debt, and its landlocked position between the failing Russian economy in the North and China in the South, Mongolia’s options may be limited in the future.

For further and more full reading on Buddhist practice in Mongolia, the Jebtsundampa Khatagt, and Dorje Shugden I would suggest reading the following:

http://thediplomat.com/2016/12/the-dalai-lama-in-mongolia-tournament-of-shadows-reborn/