CSW62: Shifting the Narrative on Women’s Rights from Normative to Actionable

Editor’s Note: This article is part of a series of MIR articles from the International Relations Students’ Society of McGill (IRSAM, Inc.)’s official delegation trip to the 62nd United Nations Commission on the Status of Women (CSW62). To read more coverage of CSW62, go to https://www.mironline.ca/category/csw-62/

Last Friday marked the end of negotiations at the 62nd Commission on the Status of Women (CSW62), a two week-long global meeting of civil society and member state representatives to discuss the priority theme: “Challenges and opportunities in achieving gender equality and the empowerment of rural women and girls” at the United Nations Headquarters in New York.

I, along with some of my fellow McGill students, had the immense privilege of representing both IRSAM, Inc. and the McGill voice at CSW62 in a trip that will, quite frankly, stay with us for the rest of our lives.

I should mention that prior to the trip, even with the ever-pervasive trend of female empowerment sweeping much of the world, across a variety of mediums, I struggled slightly with the title of “feminist.” Of course, I firmly stood behind its aims, but I was hesitant to call myself a feminist at times, for the belief that the definition meant much more than what I was doing. To be sure, belief and advocacy are essential to the movement’s momentum, but policy implementation and enforcement ensure tangible change. I asked myself, was I really qualified to call myself a feminist if I wasn’t taking the targeted action required for real change through policy? Certainly, hashtagging behind my laptop wasn’t enough.

Such is the problem with feminism: it suffers from a lack of clear interpretation, which results in ad hocery in its initiatives from a variety of perspectives. It is clear, however, that regardless of definition, all feminisms are rooted in the advancement of women’s rights and gender equality. The next problem: women’s rights and gender equality themselves often seem like a large, abstract cloud – and this perception is only reinforced by the way we have traditionally approached it from a policymaking perspective, and the way the general public sees it in their daily lives. Where does one even begin to challenge a chronic inequality, intersectionally, that has defined our modern world? An inability to address this question effectively is precisely what has led to the development of an overwhelmingly ineffectual normative narrative.

This normative narrative has not spared CSW62. In fact, the majority of side events held by NGOs or permanent missions that I attended were rooted in normative statements, such as “Norway believes in the right of equal pay,” “women’s rights are human rights,” and “we should work with men to achieve gender equality, since that is the only way.” So what? If the UN itself is plagued by such habitual normativity, how can we, as civil society, expect concrete change?

If there is to be real change in gender equality, we must shift the narrative from normative to actionable.

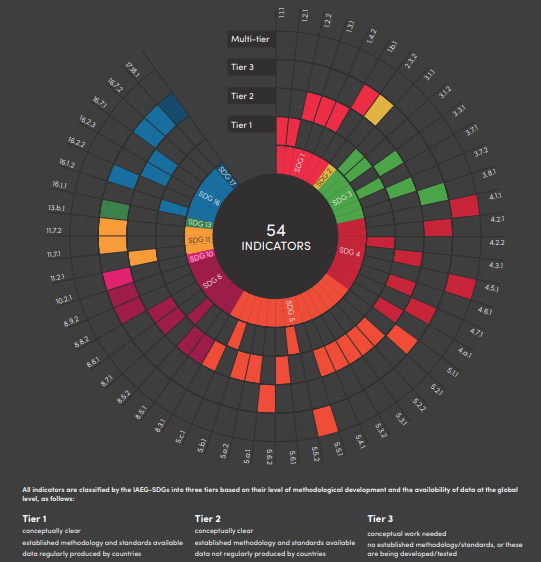

Enter the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Building on the commitments and norms of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the 2030 Agenda is comprised of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 169 targets, and 232 indicators that tackle a broad range of global challenges while incorporating an extensive cross-cutting commitment to gender equality on all fronts. It recognizes that gender equality and sustainable development are not mutually exclusive; rather, “gender inequalities manifest themselves in each and every dimension of sustainable development.” Adopted in 2015 by all 193 Member States, it is to be implemented using a comprehensive gender-responsive monitoring approach, evidenced by UN Women’s flagship report that “looks at both the ends (goals and targets) and the means (policies and processes).” If implemented successfully, the 2030 Agenda would indeed shift the narrative from normative to actionable.

Having only heard of the 2030 Agenda briefly in passing, I snuck into an event held jointly by the Permanent Mission of Germany to the UN and UN Women held on March 12 called “What Will It Take to Make the 2030 Agenda Work for Women and Girls?”, featuring an incredibly distinguished panel which included moderator Rosemary Kalapurakal; lead advisor of the 2030 Agenda and director of the Sustainable Development Cluster of UNDP; Rebeca Grynspan, Secretary General of the Ibero-American conference; Dr. Salma Nims, Secretary General of the Jordanian National Commission for Women; Shahra Razavi, Chief of the Research and Data Section at UN Women; Agnes Mirembe, an executive grassroots community development worker in Uganda; and Aizhamal Bakashova, an executive representative of a rural women’s organization in Kyrgyzstan.

Razavi spoke first on how gender-responsive implementation of the SDGs can be accelerated, highlighting a need for an improvement in gender data, statistics, and analysis as a mechanism for monitoring progress across all goals and targets, putting investments where social returns are highest for gender equality, and strengthening government accountability through gender-responsive processes and institutions to ensure resource mobilization for SDG implementation. By putting data and monitoring at the focus of SDG implementation, the 2030 Agenda is fundamentally structured in a way that ensures a global commitment to concrete action, and not just empty talk.

Nims then spoke candidly on the existing normative narrative as fueled by governments themselves – that gender equality discussions throughout all policymaking levels are “show and tell, since we can really look nice,” and as such, “we still see gender as an issue that is political.” And as long as gender is exploited, true gender equality will never be realized. The political instrumentalization of gender reduces the place of women in society to a mere commodity, diluting and even disregarding the complex dynamics of gender equality, which, in turn, prevent women’s empowerment from ever being addressed effectively or substantially. Nims further shed light on an issue that resonates across all member states – that though high-level governments and civil society are motivated, “middle management is totally isolated from such global directives, a fact that is not conducive to change whatsoever.” According to Nims, “parliaments are not only not supporting the SDGs, but they are questioning why SDGs were even adopted,” which is more than alarming for implementation of the 2030 Agenda on a national scale, to say the least.

Grynspan further posed the question, “the SDGs have changed [to be more gender-responsive monitoring-driven and actionable], but have we changed?” In other words, although our policy narrative has gradually shifted, have our mentalities? “Not much, it turns out. We just ended up ‘tagging’ our policies to the SDGs [instead of internalizing them into the system],” Kalapurakal admitted. Reversing this approach is essential so that the actionable gender equality narrative is consolidated and does not devolve into normativity, and that, as Kalapurakal put it, “gender doesn’t remain [on the] sidelines with a pink bow on it.” Grynspan further highlighted the inherent intersectionality of gender equality, drawing attention to vertical inequality, or socioeconomic inequality, and horizontal inequality, that is, between groups, noting that “the intersection of the two inequalities is the hard nucleus of discrimination in the world.” Gender equality without intersectionality is not gender equality at all, an awareness which is effectively represented in the 2030 Agenda’s targets and indicators.

I have never heard a group of women speak with so much fire, conviction, and intelligence on the topic of advancing women’s rights. All of a sudden, the previously large and abstract cloud that was gender equality was distilled into a clear framework of tangible steps that are clearly interconnected and work together toward a common end goal, highlighting exact ways in which the 17 SDGs, with an emphasis on SDG 5 (gender equality), may be implemented and mobilized effectively for gender-responsive sustainable development. If implemented fully, a positive feedback loop is created, where data “informs decision-making and contributes to holding decision-makers to account,” resulting in stronger and more comprehensive policy for the advancement of women’s rights, which in turn leads to more informative and effectual data.

Now, as a non-binding political commitment, the 2030 Agenda nonetheless lacks enforceability, which is a fact that the UN itself recognizes. Though there are “no defined consequences if countries fail to make serious efforts to meet the goals and targets,” the agenda does call for “follow-up and review processes that are open, inclusive, participatory and transparent as well as people-centred, gender-sensitive, respectful of human rights and focused on those who are furthest behind,” in line with its commitments to leave no one behind. Further, six of the 17 SGDs are still “gender-blind,” meaning they lack gender-specific indicators, according to Grynspan, which is “a clear sign of how far we need to go.” This fact stands despite a recognition of gender equality and women’s empowerment as being “integral to each of the 17 goals” and a recognition that women “possess [the] ideas and leadership to solve…the most pressing challenges of our time.” If that is the case, why, then, is the empowerment of women as an indicator excluded from more than a third of the SDGs? For example, although the cross-cutting gender-responsive nature of the 2030 Agenda as a whole is indeed unprecedented, the exclusion of gender-specific indicators from SDG 9, Innovation and Infrastructure, may well limit the scope of concentrated efforts aimed at the economic inclusion of women.

Though the 2030 Agenda does fall short on these fronts, it is nonetheless a substantial step forward for the advancement of women’s rights. I am confident that with its gender-responsive and data-driven implementation, coupled with “its rooting in human rights and understanding of these as indivisible; its universal application and pledge to leave no one behind; and its potential to serve as a tool for holding governments and other stakeholders to account,” gender equality will indeed be realized. In this way, CSW62 has both given me hope for the future of women’s rights and inspired me to shift my own narrative from normative to actionable.

Edited by Benjamin Aloi