Cyber War: Canada’s New National Security Threat

https://www.flickr.com/photos/number10gov/41516689582

https://www.flickr.com/photos/number10gov/41516689582

On September 14th, an anonymous whistleblower from within Chinese IT company Zhenhua leaked a cryptic dataset entitled “Overseas Key Information Data Base” (OKIDB). The database contained 2.4 million profiles of internet users in foreign countries who were being monitored by Zhenhua. While cybersecurity agencies were only able to decrypt 10 per cent of the OKIDB data, alarming degrees of personal information were discovered within the individual profiles: home addresses, political affiliations, details about family members, criminal histories, and bank records.

Roughly 5000 Canadian profiles were contained within the recovered data. These consisted of influential politicians, diplomats, judges, academics, and even their relatives — Zhenhua had been keeping tabs on the 11-year-old daughter of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

The personal information found in the profiles was not just taken from open sources like social media or news articles. Rather, an estimated 20 per cent of the data was stolen from closed and confidential online locations. Zhenhua’s invasion of privacy, as well as its position as a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) contractor, make the OKIDB leak a national security concern for Canada. Christopher Balding, the American academic to whom the database was leaked, says that “China is absolutely building out a massive surveillance state both domestically and internationally.”

The Zhenhua data leak has exposed a weakness in Canada’s national security strategy: cybersecurity. If a small startup was able to access the private information of thousands of Canadians, then what could a more capable actor have accomplished? In the modern global political arena, where classified and crucial data is stored on the web, cybersecurity is national security. And in this new environment, Canada is lagging behind.

The aching question for Canadians is simple: why collect information on 11-year-old children on the other side of the globe?

“That, to me, is the question that national security agencies in the West have to figure out,” says Stephanie Carvin, a professor of international relations at Carleton University.

A 2019 parliamentary report shows that last month’s Zhenhua affair was not an anomaly in Canada’s history with cybersecurity breaches. In 2014, the database of the Canadian National Research Council — a state hub for technological R&D projects – was breached by CCP-sponsored actors. Canadian officials also cited fears of the Russian military’s efforts to “target critical infrastructure,” particularly in fields related to COVID-19 vaccine research.

Yet, security and privacy in Canada are not just threatened by foreign actors; some of the greatest breaches have been perpetrated by people at home. Last year alone, two Canadians were arrested in connection to a hack of the province of Quebec’s tax collection agency Revenu Québec. Additionally, Desjardins Group, Canada’s largest federation of credit unions, experienced a breach by one of its own employees, which compromised the privacy of 4.2 million members.

The harvesting of online data is becoming the gold rush of our time. Private actors, like Amazon and Facebook, rigorously collect users’ personal information to accurately predict interests and behaviour. Not only does this allow these tech giants to keep users engaged, it gives them such a significant advantage over their competitors that they are gradually monopolizing their markets.

User data is also being harvested by state actors, but for reasons which are less clear. US President Donald Trump signed an executive order banning TikTok and WeChat in August, stating that applications “owned by companies in the People’s Republic of China […] threaten the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States.” In addition, social media can be used by governments as a weapon to favourably alter public opinion in foreign countries. For instance, the Kremlin-sponsored agencies that interfered in the 2016 US election spread political messages through hoards of fake Facebook accounts. Zhenhua claims to have developed a social media content-manipulating software with similar capabilities.

A spokesperson for Zhenhua stated: “We are a private company, our customers are research organizations and business groups.” Yet, the CCP and People’s Liberation Army appear frequently on the company’s clientele list.

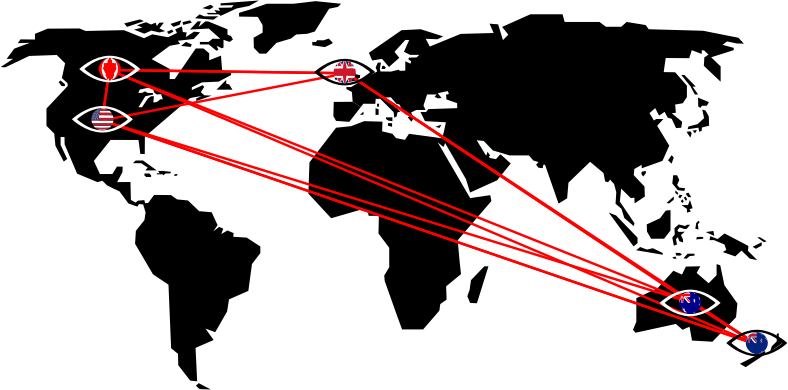

While Canada is a member of The Five Eyes intelligence alliance alongside the US, UK, Australia, and New Zealand, it has lagged behind its allies in addressing several key cyber threats. Canada is the only Five Eyes nation that has not blocked Chinese telecom giant Huawei from its 5G networks. Though Huawei is a private company, the CCP’s 2017 National Intelligence Law requires private firms to cooperate with the state in matters of national intelligence. There is little evidence to date to suggest that the CCP has used Huawei to conduct cyber espionage in Canada. Nevertheless, granting Huawei access to Canada’s 5G networks — which connect people, machinery, and devices to a much greater extent than earlier wireless generations — would worsen the damage if the CCP were to invoke the National Intelligence Law; precisely why other countries have blocked Huawei from 5G.

Canada is lagging behind in the international cybersecurity race. So what can it do to catch up?

Canada could attempt to pacify cyber threats through diplomacy. The most effective way to do this would be to land cyber accords with countries that pose potential threats. In 2015, US President Barack Obama and CCP leader Xi Jinping reached a cybersecurity agreement that aimed to crack down on intellectual property theft. UK Prime Minister David Cameron forged a similar deal in that same year. Following his Five Eyes allies, Prime Minister Trudeau instructed his national security advisor to form a cyber accord with China in 2016. Four years later, such an accord is yet to be reached.

If one option for Canada is to offer an open hand, another option is for the country to clench its fists. China’s “hostage” detainment of two Canadians in response to the RCMP’s arrest of Huawei CFO Meng Wanzhou has shown that attempts at diplomacy can sometimes disappoint. Instead, Canada could heavily invest its time and resources into building a strong national cybersecurity shield — one strong enough to defend from both foreign and domestic threats.

The security services of the Five Eyes nations, when considered individually, are world-class. Together, they are unmatched. With increased coordination in the realm of cyber defence, Canada would have a much better shot at addressing cybersecurity threats. For instance, Canada could adopt a national cybersecurity program similar to the UK’s Active Cyber Defense Programme, which offers email checks, web checks, and online vulnerability disclosures to citizens.

Canada must forge both deals and shields in the cyber world, because the threats it contains are now imminent. Diplomatic engagement with other countries, as well as defences to protect from domestic threats, will increase Canada’s ability to protect its citizens, institutions, and sovereignty in the twenty-first century global political arena.

Featured image: Canadian PM Justin Trudeau meets with Five Eyes allies at the National Cyber Security Centre in London. “PM at NCSC” by Number 10, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Edited by Rebecka Eriksdotter Pieder