Deal or No Nuclear Deal: How the Crisis with Iran began and Why the End is Now in Sight

The history of scandals, virulent denunciations and accusations, and near warfare between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran casts doubt over the ongoing nuclear negotiations. From the perspective of many in the West, the Iran Hostage Crisis, the Iran-Contra scandal, Iranian support of Hezbollah, and the 2002 revelation of Iran’s clandestine nuclear facilities all demonstrate how little the clerical regime cares about the rules and laws of the international order. From the other side, the CIA’s role in the 1953 coup d’état and United States’ painting of Iran as a pariah state ever since the 1979 Islamic Revolution has done little to remedy an already injured confidence in the West. In this first article of a two part series, a historical examination of Iran’s nuclear program reveals that the clerical regime is not motivated by a desire to launch an unbridled nuclear war against all the enemies it has denounced in years past, but rather, by survival considerations. In the second article, this evidence along with news from the talks will demonstrate why Iran is likely to finalize a nuclear deal despite the claims of many that the Islamic Republic is toying with Western goodwill.

The history of scandals, virulent denunciations and accusations, and near warfare between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran casts doubt over the ongoing nuclear negotiations. From the perspective of many in the West, the Iran Hostage Crisis, the Iran-Contra scandal, Iranian support of Hezbollah, and the 2002 revelation of Iran’s clandestine nuclear facilities all demonstrate how little the clerical regime cares about the rules and laws of the international order. From the other side, the CIA’s role in the 1953 coup d’état and United States’ painting of Iran as a pariah state ever since the 1979 Islamic Revolution has done little to remedy an already injured confidence in the West. In this first article of a two part series, a historical examination of Iran’s nuclear program reveals that the clerical regime is not motivated by a desire to launch an unbridled nuclear war against all the enemies it has denounced in years past, but rather, by survival considerations. In the second article, this evidence along with news from the talks will demonstrate why Iran is likely to finalize a nuclear deal despite the claims of many that the Islamic Republic is toying with Western goodwill.

It is time to acknowledge that the Islamic Republic of Iran is not anathema to the international order and that negotiations that allow it to maintain nuclear facilities for civilian and medicinal purposes is the country’s right under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). With oil prices plummeting, (Iran’s critical source of wealth much needed to buoy its economy under Western sanctions), the Islamic Republic is far less likely to walk out. Thus it is essential that the ongoing negotiations between Secretary of State John Kerry and Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif are not scuttled by the accusations of hardliners in both countries who view all talks and compromises as unacceptable. These hardliners willfully ignore the historical context that bred hostilities between the United States and Iran in the first place and led to the development of Iran’s nuclear program.

With the ambition of becoming a regional hegemon, the Shah poured tremendous funds into advancing his country’s military technology and civilian infrastructure. As such he declared in 1974 his intentions to possess ‘as soon as possible’ nuclear technology with the output of 23,000 Megawatts.[1] The Atomic Energy Organization of Iran was subsequently founded to achieve this goal with substantial aid coming from the Shah’s allies in Western Europe and the United States. Examples of the United State’s extraordinary commitment to Iran’s program include a 1977 deal to exchange nuclear technology and work together on the safety of nuclear projects as well as the US-Iran Nuclear Energy Agreement of 1978 which accorded “most favored nation status” to Iran for spent fuel reprocessing.[2] Germany and France also contributed greatly to Iran’s nuclear development in the 1970’s by accepting Iranian students into the nuclear science and engineering programs at their universities as well as agreeing to nuclear fuel contracts.[3] Nor were the Shah’s goals for nuclear research purely civil as one of his close confidants confessed in his diary that, “His Imperial Majesty has a great vision for this country, which, though he denies it, probably includes the manufacturing of a nuclear deterrent.”[4] That Western Europe and the United States provided the critical aid and impetus for Iran’s nuclear program highlights a central hypocrisy of their Cold War policy, which was that so long as the government in Iran was an ally against communism, concerns about nuclear non-proliferation were silenced.

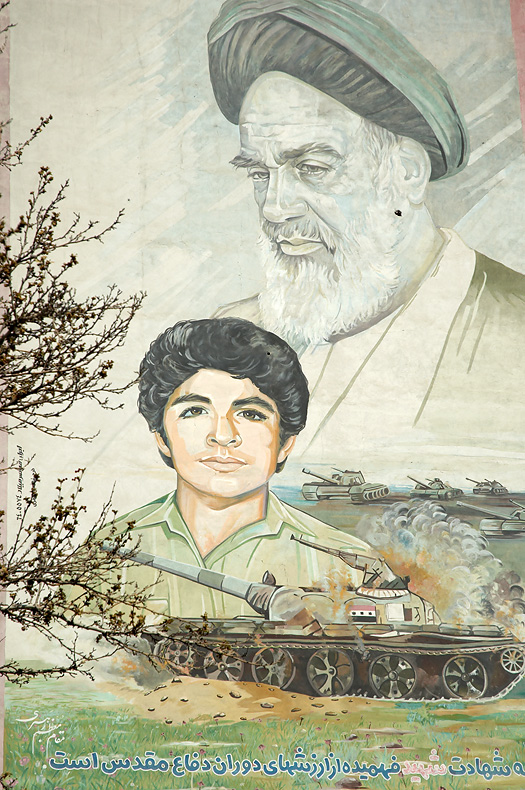

The ascendance of the Ayatollah Khomeini to power nearly terminated Iran’s nuclear program, as the cleric viewed such technology as a means of keeping Iran dependent on the West. Khomeini ultimately changed his opinion due to the impunity with which Saddam Hussein used chemical weapons against Iranian forces coupled with a serious energy crisis brought on by the demands of the war. Although the Iran-Iraq War witnessed atrocities committed by both sides, it was Saddam Hussein who launched the invasion of Iran in the first place and it was by his orders that Iraq grossly violated the laws of war set down in the Geneva Conventions. The West should have taken him to task for these violations, but its failure to do so eroded the credibility international humanitarian law from the Iranian perspective and confirmed their idea that the West was so hell-bent on toppling the Islamic Republic, that it would even back a tyrannical war-criminal. This perpetuated the Iranian worldview of isolation and alienation, which has now provoked the country to seek its own means of deterring outside powers from attacking. The 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States and the 2011 NATO airstrikes that helped to topple Muammar Gaddafi have only added credence to the Iranian hardliners’ position. They argue that if Iran capitulates and gives up the threat of pursuing nuclear weapons the United States will back regime change with military force when the cracks appear in the façade of Iran’s authoritarian regime.

The ascendance of the Ayatollah Khomeini to power nearly terminated Iran’s nuclear program, as the cleric viewed such technology as a means of keeping Iran dependent on the West. Khomeini ultimately changed his opinion due to the impunity with which Saddam Hussein used chemical weapons against Iranian forces coupled with a serious energy crisis brought on by the demands of the war. Although the Iran-Iraq War witnessed atrocities committed by both sides, it was Saddam Hussein who launched the invasion of Iran in the first place and it was by his orders that Iraq grossly violated the laws of war set down in the Geneva Conventions. The West should have taken him to task for these violations, but its failure to do so eroded the credibility international humanitarian law from the Iranian perspective and confirmed their idea that the West was so hell-bent on toppling the Islamic Republic, that it would even back a tyrannical war-criminal. This perpetuated the Iranian worldview of isolation and alienation, which has now provoked the country to seek its own means of deterring outside powers from attacking. The 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States and the 2011 NATO airstrikes that helped to topple Muammar Gaddafi have only added credence to the Iranian hardliners’ position. They argue that if Iran capitulates and gives up the threat of pursuing nuclear weapons the United States will back regime change with military force when the cracks appear in the façade of Iran’s authoritarian regime.

The instability and violence that continues to rage throughout Iraq and Libya should serve as enough of a cautionary tale against those Western hawks who espouse the rash view that Iran’s nuclear facilities should be bombed. As if this were not enough, the head of the Atomic Energy Association, Hans Blix, has also stated that “if the decision to build a bomb has not yet been taken, a military strike would ensure more than ever that it is.”[5] Beyond this caution, the Iran-Iraq War offers further explanatory power as to how Iran’s regime and its people would react to such an act. Any attack on Iran would cement the Ayatollah’s hold on power rather than working to undermine it, because of the long and tragic history of domination by Western powers that Iranians have endured. Additionally, the hardliners in the Iranian government would utilize a war with the West in a similar manner to the consolidation of power witnessed during the Iran-Iraq war by the Ayatollah Khomeini. In a similar vein, two Iranian human rights advocates wrote that, “human rights violators will use this opportunity to silence their critics by labeling them as the enemy’s fifth column.”[6] While a military option of dealing with a potential nuclear security threat from Iran shouldn’t be taken off the table, it should absolutely be the option of last resort due to the likelihood that it would strengthen the clerics’ grip on power and further destabilize an already volatile region.

All photos from Flickr Creative Commons.

Works Cited

[1] Mustafa Kibaroglu, “Iran’s Nuclear Ambitions from a Historical Perspective and the Attitude of the West,” (Middle Eastern Studies, Vol. 43, No. 2, March 2007), 229.

[2] Ibid, 230.

[3] Ibid, 231.

[4] Ray Takeyh, “Guardians of the Revolution: Iran and the World in the Age of the Ayatollahs,” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 243.

[5] “Israeli Strike Would ‘Ensure’ Iran Seeks Bomb, Warns Blix,” AFP (Nov. 12, 2011).

[6] Shirin Ebadi and Hadi Ghaemi, “The Human Rights Case Against Attacking Iran,” The New York Times (Feb. 8, 2005).